University of Idaho murder suspect’s alibi defense puts spotlight on cellphone data analyst

When Bryan Kohberger’s lawyers filed an updated alibi defense last week, suggesting cellphone tower data will show the man suspected in the slayings of four University of Idaho students was not in the area of the crime scene when they were killed, they said they planned to turn to an Arizona-based cell data analyst for key testimony.

It wouldn’t be the first time that Sy Ray has been asked to be an expert witness in a high-profile murder trial, although he said Friday that, out of the more than 100 times he’s testified in state and federal cases, it has typically been for the prosecution.

Now, Ray’s involvement in the case of the four college students fatally stabbed in their off-campus apartment house in November 2022, which continues to stir speculation over why someone would commit the gruesome act, is putting a spotlight on his expertise after past scrutiny over his credentials.

A timeline of the Idaho stabbings

Ray declined to address the Kohberger case, as a judge issued a gag order last year preventing many involved from speaking publicly, but he said in general that it takes “competent experts with adequate experience to interpret call detail records.”

“Where the challenges come in is when there’s a different level of experience,” he added, “and some of these records can be extremely complicated.”

Ray, a former Gilbert, Arizona, police detective, founded ZetX Corp., a company specializing in cellular geolocation mapping, in 2014. In the courtroom, Ray has found himself and his mapping software, Trax, under questions about reliability before.

“I’ve seen in previous cases where his credibility has been brought into question,” said Mark Pfoff, a cellular technology expert and former sheriff’s detective in El Paso County, Colorado.

Pfoff testified for the defense in a 2022 hearing related to the case of a man accused of stalking an ex-girlfriend. But the judge barred prosecutors from using Ray’s software data.

District Court Judge Juan Villaseñor ruled that ZetX’s Trax mapping was inadmissible and based on a “sea of unreliability” after other experts found the technology to be problematic.

“For one, the Court doesn’t find Ray credible,” Villaseñor wrote, adding: “He inflated his credentials, inaccurately claiming to be an engineer.” He went on to say that Ray has “no qualifications, licenses, or credentials to support” calling himself an engineer and that there’s “no evidence that Ray’s taken any engineering classes.”

Villaseñor also took exception with how the Trax algorithm wasn’t open to “scientific scrutiny.”

“While Ray stands by his formula, it hasn’t gained traction in the scientific community,” the judge wrote. “The methodology and algorithm aren’t published or subject to peer review, and they’ve been routinely labeled as junk science by the relevant scientific community.”

Ray said on Friday that he agreed with the defense in that there was inaccuracy with the data, but the case was an anomaly. NBC News found other cases, including in Pennsylvania and Michigan, in which Ray’s credibility and data were questioned in hearings, but judges ultimately deemed them admissible.

“I absolutely stand by the product,” Ray said.

He added that the Colorado judge denigrated his background unfairly and that he was misquoted and misinterpreted about discussing how he and engineers interpret call records. He said he has gone into the field to research how a cellphone will connect to certain cell sites, which an engineer would not need to do.

“In a way, I’m doing something the engineers don’t do to figure out how to do this better,” he said Friday, adding that the Trax software is “testable” by others.

It’s unclear how many law enforcement agencies currently use Trax, but Ray in 2022 said he provided training to more than 8,000 law enforcement officers, prosecutors and defense experts. LexisNexis purchased ZetX in 2021. The data analytics company said in a statement that it is “proud to support a broad range of law enforcement agencies,” but does not disclose customer information.

According to a background of Ray’s experience filed in court documents by Kohberger’s defense team, he ended his role as a director for LexisNexis Special Services last year.

He has also appeared on various true crime television shows, including NBC’s “Dateline,” and hosts a true crime podcast with his wife, “Socialite Crime Club,” in which they “discuss their involvement in criminal cases from around the world and what it takes to solve complex investigations.”

Idaho alibi

In a 10-page filing Wednesday signed by Anne Taylor, Kohberger’s lead public defender, his lawyers said they would call on Ray to help corroborate their client’s alibi.

At the time of the slayings, Kohberger was a doctoral student at Washington State University and living in Pullman, Washington, about 10 miles west of Moscow, Idaho, where the University of Idaho is located.

In an affidavit following Kohberger’s arrest weeks after the killings, prosecutors said he was linked to the scene through male DNA discovered on a knife sheath left at the victims’ apartment house.

In addition, investigators said, they tracked Kohberger in the area of the home through his cellphone use and surveillance that picked up a Hyundai Elantra that they believed he was driving.

Kohberher’s alibi defense said he would go for nighttime drives, and that those only increased during the school year.

“This is supported by data from Mr. Kohberger’s phone showing him in the countryside late at night and/or in the early morning on several occasions,” they wrote. “The phone data includes numerous photographs taken on several different late evenings and early mornings, including in November, depicting the night sky.”

In the early morning hours of Nov. 13, 2022, when the killings of Kaylee Goncalves, 21; Madison Mogen, 21; Xana Kernodle, 20; and Kernodle’s boyfriend, Ethan Chapin, 20, occurred, Kohberger “was out driving” in an area south of Pullman and west of Moscow.

But, the defense team added, Ray’s testimony intends to show that “Kohberger’s mobile device did not travel east on the Moscow-Pullman Highway in the early morning hours of November 13th, and thus could not be the vehicle captured on video along the Moscow-Pullman highway near Floyd’s Cannabis shop.”

They said that Ray would be able to share further analysis that would be based on discovery provided by the prosecution, but if such information is “not disclosed, Mr. Ray’s testimony will also reveal that critical exculpatory evidence, further corroborating Mr. Kohberger’s alibi, was either not preserved or has been withheld.”

Prosecutors had said in its affidavit that a search warrant provided Kohberger’s cellphone data for the 24 hours before and after the incident, and it showed that he left his home two hours before the killings and then turned his phone off, only to turn it on again afterward, when it was seen traveling from Idaho to Pullman.

A grand jury last May indicted Kohberger on four counts of murder and burglary, and a judge entered a not guilty plea on his behalf.

A trial was expected to begin last October, but has been delayed, with a change of venue hearing scheduled for June 27.

Cellphone analysis

While further detail about how Ray would support the defense’s alibi claim is unclear, the use of such cellphone mapping technology and forensics has become a sought-after capability in legal proceedings, experts say, as prosecutors attempt to prove a defendant was at the scene of a crime. Defense teams as well may bring on their own experts to refute law enforcement’s analysis.

Kevin Horan, a retired FBI agent and co-founder of Precision Cellular Analysis, an Ohio-based firm that consults in legal cases, said mapping software generally works the same: It matches cell site information, known as call detail records, with a list of cell towers, and plots it onto a map.

He said analysts can determine from which side, or sector, of a cell tower a cellphone utilized. In criminal cases, he added, investigators can use that information to analyze whether the phone was in a certain vicinity of where the crime happened.

“Ultimately the question of where the phone was during the date and time in question is answered by the jury, who must decide based on all available evidence if the defendant and his phone were at the crime scene,” Horan said. “Cellphone evidence like this simply helps the jury draw these types of conclusions. A properly trained cellphone expert will never testify that, based on the cell data, the defendant or his phone were at a crime scene.”

Horan said Ray’s Trax mapping software has stood out from other programs because it includes an estimated coverage area of a cell site, which he finds “highly problematic and misleading,” and that only a “drive test” in which scanning gear is used can help determine a cell site’s full coverage area.

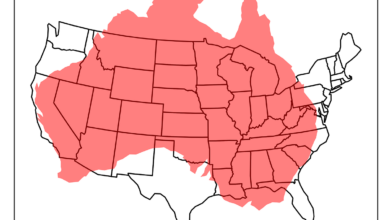

Ray said the company he founded has a database in which every cell site in the U.S. — hundreds of thousands — have been mapped, updated over time and archived.

“We’ve been drive-testing since 2014, and every drive test we do, we archive,” Ray said. “Nobody will ever be able to drive-test every cell site. It’s an impossible task.”

Horan said in general it’s imperative for the data collected to be accurate and interpreted correctly.

“People’s lives, their liberty, is on the line, and we certainly don’t want to convict someone who’s innocent or use evidence that’s questionable and could come back at a later time,” he said.