AI @ Harvard | Harvard Magazine

How is artificial intelligence reshaping the notion of original scholarship? How are faculty using the technology in their research and teaching, and what are administrators doing with the tools to streamline their work? A May 1 symposium convened by Harvard’s Faculty of Arts and Sciences (FAS) considered the many ways AI is already changing the nature of academic research, teaching, and administration. Because large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT have initiated dramatic upheavals in the way students and faculty acquire and process information, even the Harvard Library, as a trusted curator of knowledge, must respond. Preeminent library collections like Harvard’s could play an important role in future iterations of LLMs, once the legal issues surrounding fair use of copyrighted materials are settled.

FAS dean Hopi Hoekstra reflected on the challenges and opportunities presented by AI during the past nine months. “We’ve been investing in the positives,” she said “looking for all the ways that we can channel this powerful technology to create a better world, from the sciences to the arts.” Paul professor of the practice of government and technology Latanya Sweeney, who has co-chaired the FAS Artificial Intelligence Systems Working Group since the summer of 2023, emphasized in her introductory remarks that “this is a pivotal moment for all of us in society,” and—on the same day that Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, spoke in Memorial Church—urged community engagement and collaboration to help shape AI’s future impact. Students in two of Sweeney’s classes, Government 1430, “Tech Science to Save the World,” and Democracy, Politics, and Institutions 642, “Grand Challenges in Technology-Society Clashes,” presented posters of their coursework during the break between sessions.

Original Scholarship in an AI World

The day opened with a panel discussion on the meaning of original scholarship in the age of AI. The speakers brought their distinct disciplinary perspectives to the question of what constitutes original work, and what represents acceptable use of AI tools.

Providing an historical perspective, professor of the history of science Alex Csiszar began by questioning the idea that authorship itself is a stable notion. Shifts in the understanding of what it means to publish an original text, including the twentieth-century emergence of “contributorship” on scientific papers with a large number of authors, suggest that while AI may accelerate the need for new models to meet the needs of a highly collaborative digital era, the unattributed, digest-like forms in which ChatGPT presents information are not new. Commonplace books of the seventeenth century, he explained, gathered quotations and information from “all over the place” without attribution. AI will “not necessarily revolutionize anything,” he said, “but it’s going to force us to take seriously a whole bunch of problems that already existed.”

Kingsley professor of art, film and visual studies David Joselit said that similar questions arose in the arts when technologies such as photography and film became ubiquitous. He advocated for understanding AI not just as a tool but as a genre that will reshape creative and scholarly outputs. And he called for critical engagement with the training data used to create LLMs, pointing to their highly curated nature and potential biases.

Furer professor of economics Melissa Dell highlighted the problem of duplication of original material—one that is poised to become much worse as LLMs parrot and essentially replicate existing information without citing sources. She highlighted the important role that libraries (the subject of a later session—see below) could play to counteract that diluting effect: “How do we get the information that’s in Widener, buried, and in the offsite storage,” she asked, and work out the legal obstacles to “make it all accessible” which will enhance scholarship in social science disciplines?

Harvard University Distinguished Service Professor Mike Smith, Finley professor of engineering and applied sciences, a computer scientist, suggested taking a practical approach to the use of AI in student work in his field. He views the tool as a means of enhancing scholarly work, without necessarily altering the nature of authorship. In his own courses, Smith said, he encourages the use of AI, but emphasized the importance of dialogue between students and instructors to ensure that the tool supplements, rather than defeats, the engagement of students in their own learning.

Research, Teaching, Administration, and Training

That featured opening panel was followed by three concurrent sessions on the use of AI: in faculty research; in teaching tools and innovation; and in the practical preparation of undergraduates and doctoral candidates alike for a world transformed by AI-driven change.

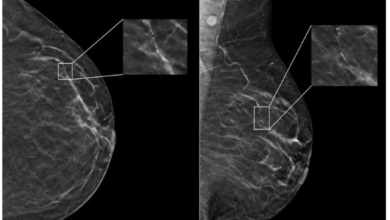

Faculty researchers highlighted the fact that ChatGPT allows users to make natural language queries—the form of questions posed most often to Google—of large, complex databases. The technology is also useful for generating new ideas and predicting human preferences, including for political issues and candidates. Moncher professor of astronomy Christopher Stubbs, who is Hoekstra’s special adviser for AI, described how he has used AI to automate tasks, analyze data, generate code, and even predict the windspeed at a telescope in Chile that produces blurred images in heavy wind. (Selected students from his course, General Education 1188: “Rise of the Machines? Understanding and Using Generative AI,” presented their final projects later in the day.) Assistant professor of computer science Stephanie Gil hailed the utility of generative AI for improving the decision-making capabilities of autonomous vehicles and robots.

In the realm of pedagogy, innovative uses abound. One professor has begun using AI models to analyze how ballet has changed over time. And Harvard’s information technology services organization (HUIT) has developed a specialized tutor bot that runs on Slack, a messaging tool. The bot uses “retrieval-augmented generation” to provide accurate information to students: instructors can upload documents, papers, and readings, and the bot will draw upon that information, citing its sources when answering questions.

Administrators at the symposium described how they have used AI to make transcripts of meetings (recorded with participant assent), generate high-level summaries, and highlight action items that need to be followed up. Strategic director of endowment and gifts Naveen Reddy gave a particularly memorable example when he described creating a custom GPT model to help him manage Harvard’s 8,000 restricted-use endowment funds. The original donors earmarked their gifts for specific uses, and Reddy’s role is to help the University advance its teaching and research mission by allocating the funds appropriately and efficiently. The gift terms were in one Excel spreadsheet, balances in another, and prior year expenditures in yet another database. Reddy provided this information to his GPT model, and can now make natural language queries to quickly query multiple datasets through a single interface.

Among the fascinating presentations were several by leaders of the Harvard Library, one of the world’s largest. University librarian Martha Whitehead began by drawing a parallel between generative AI and research libraries, noting that both “draw upon a broad corpus of existing information to answer questions and generate new information.” The fundamental value of the Harvard Library, she continued, is that it provides “access to trustworthy information spanning centuries, regions, and voices around the globe.” And part of the library’s aspiration is to make their curated datasets available through LLM-enabled interfaces. The library aims to do so in the same spirit that it makes the pre-1923 Google Books corpus available—and according to similar legal reasoning: the library can share its legally acquired collection with students and researchers according to the principles of fair use. “We’re immersed in the ethics of information,” Whitehead emphasized, from intellectual property, to copyright, to plagiarism: what director of copyright and information policy Kyle Courtney has referred to—tongue-in-cheek—as “copyright’s close cousin.”

Other presentations covered patterns of student AI use (by the fall of 2023, 65 percent of surveyed students said they had used or planned to use generative AI for academic work, 80 percent using ChatGPT specifically); legal aspects of copyrighted information (libraries, with their vast and legitimate content collections, are well-positioned to support the ethical development of AI technologies, although the legal landscape will evolve slowly); and a pilot project that allows patrons to “Talk to HOLLIS,” the library’s online catalog.

“The grand challenge for the Harvard Library,” concluded associate University librarian and managing director for library technology Stu Snydman, “is to enable researchers and students to find the right content when needed to support world-class research, teaching, and learning, amidst a massive and ever-growing sea of information. And to ensure that users have confidence that the Library is connecting them to trustworthy sources.”

The challenges facing libraries in an age of AI are a microcosm of those confronting institutions of higher learning: how to ensure that they advance knowledge and educate students who will bring an informed and ethical perspective to their contributions to society. The FAS symposium was one of many efforts underway across the University in pursuit of those aims.