Data, But Make It Fashion

Style Points is a weekly column about how fashion intersects with the wider world.

If you read much current trend reporting, you might think that skinny jeans are verboten or that Sambas have finally reached their saturation point. Madé Lapuerta doesn’t necessarily see it that way. The creator of the Instagram account @databutmakeitfashion has become somewhat of a counterintuitive force in the industry, dispensing data-driven analyses of trends and trendlets to her nearly 300,000 followers. Like a stock ticker, her account keeps track of the faintest fluctuations: tenniscore is up, coquette style is down. She’s become a bullshit detector in an age of ever more confusing and esoteric TikTok-bred trends.

Lapuerta got her start the way so many women in media did: through boy band fan culture. “I don’t know if you remember the era of One Direction,” she says, instantly making me feel ancient. Back then, she was in eighth grade and deep in 1D Tumblr. Wanting to put one of their songs on her blog, she started learning to code. At the time, she says, “I didn’t know anything about fashion, and you could tell by how I dressed.” But later, as a junior at Harvard, she watched the documentary McQueen and had an awakening. “I thought fashion was just a lot of logos, and there’s some truth to that, but it’s obviously so much more,” she says now. “I instantly fell in love. I thought I would be a computer science person, and then on the side, I would have an interest in fashion.” She didn’t realize she could combine her passions until that summer, when she was interning at Google.

When she would read about what was deemed in or out, “I was like, ‘Wait, okay, hold up, though. How do I actually know? Is this just one influencer’s opinion, or is this actually in style?’” she says. “Coming from a numbers and engineering background, it was very important for me to verify it. And a lot of times I find that it’s not verified. It’s not actually in.” Lapuerta sees herself as distinct from trend forecasters, who are more like soothsayers, looking ahead to future seasons. “I see myself as a data scientist who really likes fashion,” she says. “I don’t do as many predictions. I try and stay very current and real-time.”

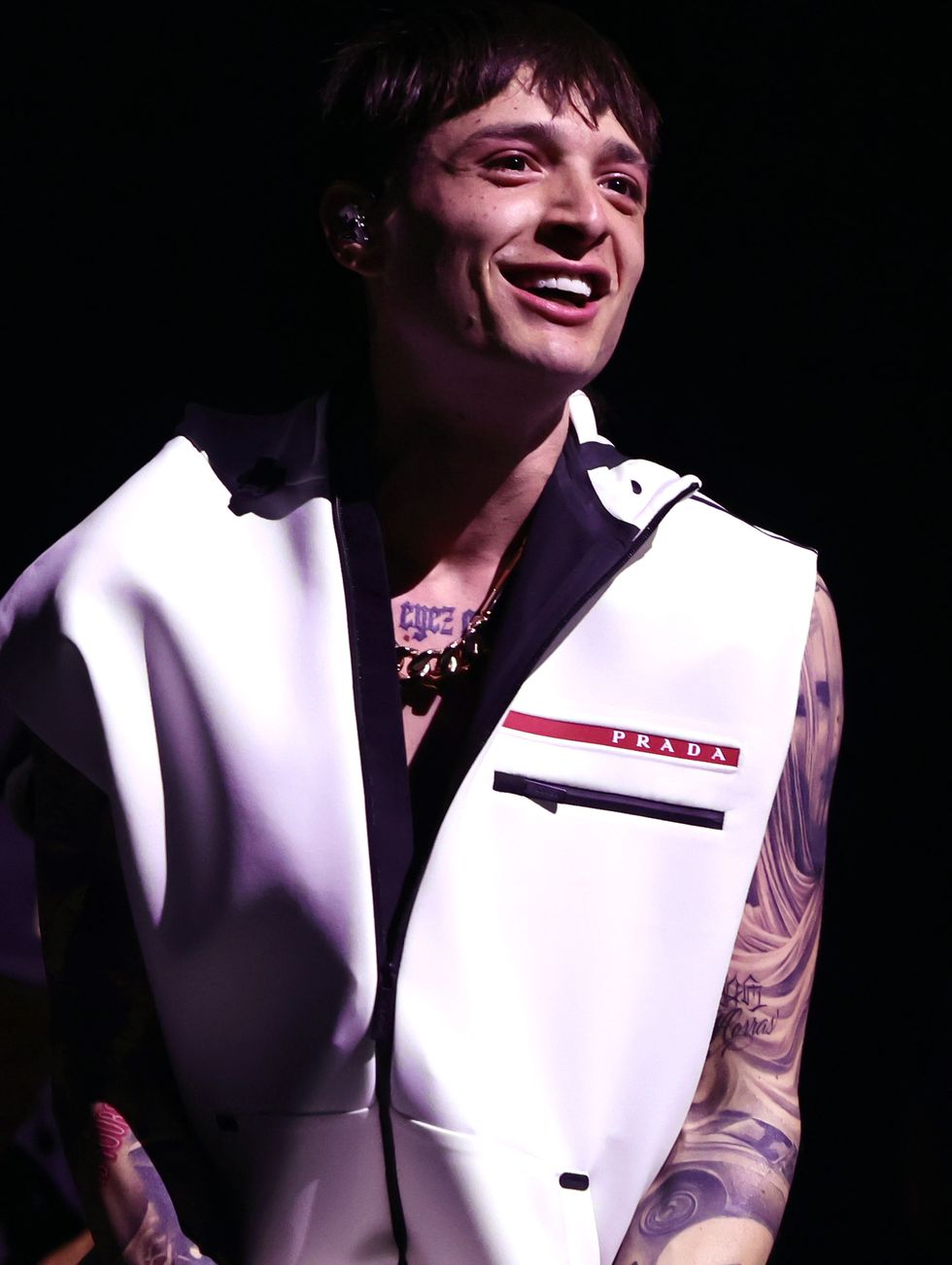

She engages in “social listening,” combing articles and posts about a specific trend or brand, then running a sentiment analysis, “which is a data analytics method of quantifying how positive language is,” she explains. “I’ll also look at tweets because there’s a lot of fashion discourse that happens on X [formerly known as Twitter].” She scrutinizes likes, finding, for example, that Zendaya receives a higher number on her posts than other celebrities. And at the reaction to seismic moments at the celebrity-fashion nexus, whether it’s Peso Pluma wearing Prada at Coachella or Daisy Edgar-Jones and Paul Mescal in Gucci at the Golden Globes. All of that, she says, “can help me quantify how trends are changing or what’s popular in fashion and put a number behind it.” Like, say, 75: the percent increase in interest in Stella McCartney that Lapuerta clocked after Taylor Swift wore the designer’s bag at Coachella.

Even negative feedback can sometimes indicate interest: often, when Lapuerta posts that something is going up in popularity, she’ll get comments from people who hate that thing. “That’s okay, but it’s coming from somewhere,” she says. “If you don’t like the trend, anytime that you talk about it, it raises its popularity, or it encourages more discussion and then people look at it more. I think it’s interesting when people hate on trends so publicly, and then you take a look and realize people secretly like them. A lot of negative press eventually turns into attention, and eventually that trend increases in positivity.”

The process isn’t an exact science, and it comes with some limitations, as she’s the first to admit. If she sees tweets about a new Miley Cyrus look that “use language like, ‘This outfit is sick,’ or ‘I’m dead,’ the sentiment analysis might pick that up as very negative, whereas you and I both know they’re hyping up the outfit,” she says. “That’s something that definitely requires manual intervention.”

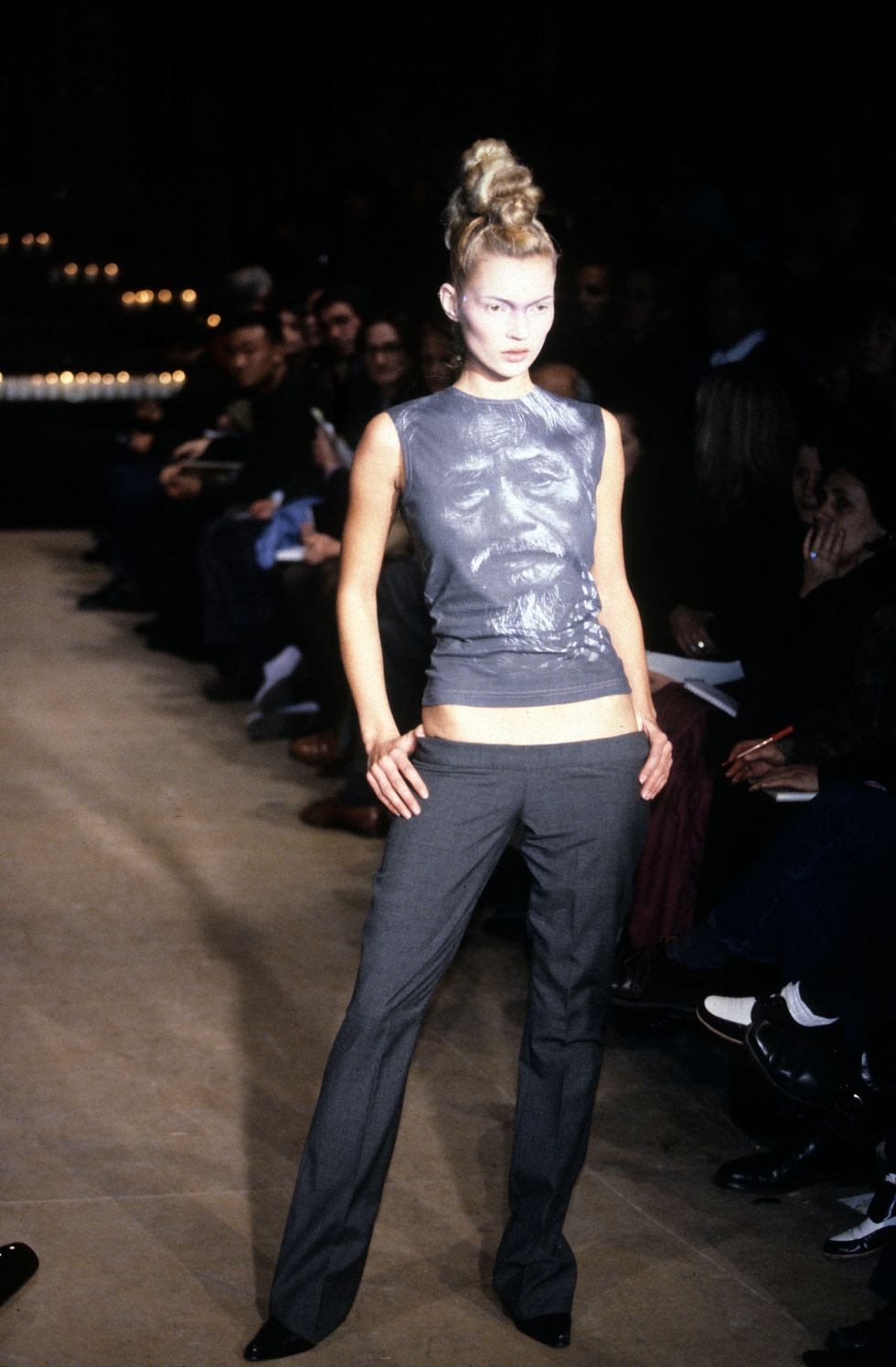

She also notes that when she’s perusing fashion X, she may be looking at a sampling of individuals who are more engaged and in tune with industry news, compared to the average person. When some on the platform were touting the return of the McQueen bumster silhouette, she found a lot of conversation about it among high-fashion-oriented social media users. But her research suggested the revival had yet to hit the mainstream, “even though a lot of people within the runway sphere were talking about it.”

Amid the cacophony of endless TikTok trends, Lapuerta believes that data can be a tool for making sense of the madness. For example, the mob wife trend, which, according to her research, peaked around the beginning of the year, then took a steep dive. “It’s interesting to try and take an objective look at the life cycle of a trend, because now you see that it’s months, or sometimes a couple of weeks.” Whereas something like ballet flats, which have hung on for two years, “are not so much a social media fad. This is something that people just like.”

While some fashion commentators have abandoned the idea of the hemline index, or fashion trend-as-economic-indicator, Lapuerta describes herself as “a big believer” in the concept. “One that I posted about that I stand by was the rise of the office siren,” which she sees as “an interesting way to get people really excited about going back into the office. I know it made me excited to get dressed up and go to work.”

Since starting her account, Lapuerta has released four trend books summarizing her findings. And she’s been experimenting with new formats, like style icon starter packs and “what’s in my bag” features (and even a guide to dressing like your favorite programming language.) But the most important function of her account, she says, is as “a tool to let people who are underrepresented in technology or STEM fields understand that what makes you different can be what makes you successful. I struggled so much in college, and in my first internships, feeling like I didn’t fit in in tech. Even if you don’t like fashion, even if you might not love the trends that I post about, I hope this shows younger people or women or anyone who’s underrepresented in tech that this is still a space for us. Even if you strongly deviate from what the tech-bro stereotype looks like.”