As new laws are proposed, Colorado companies share how they use AI to make business better

Wouldn’t it be nice to have someone whisper in your ear the right words to say at the exact moment you need them?

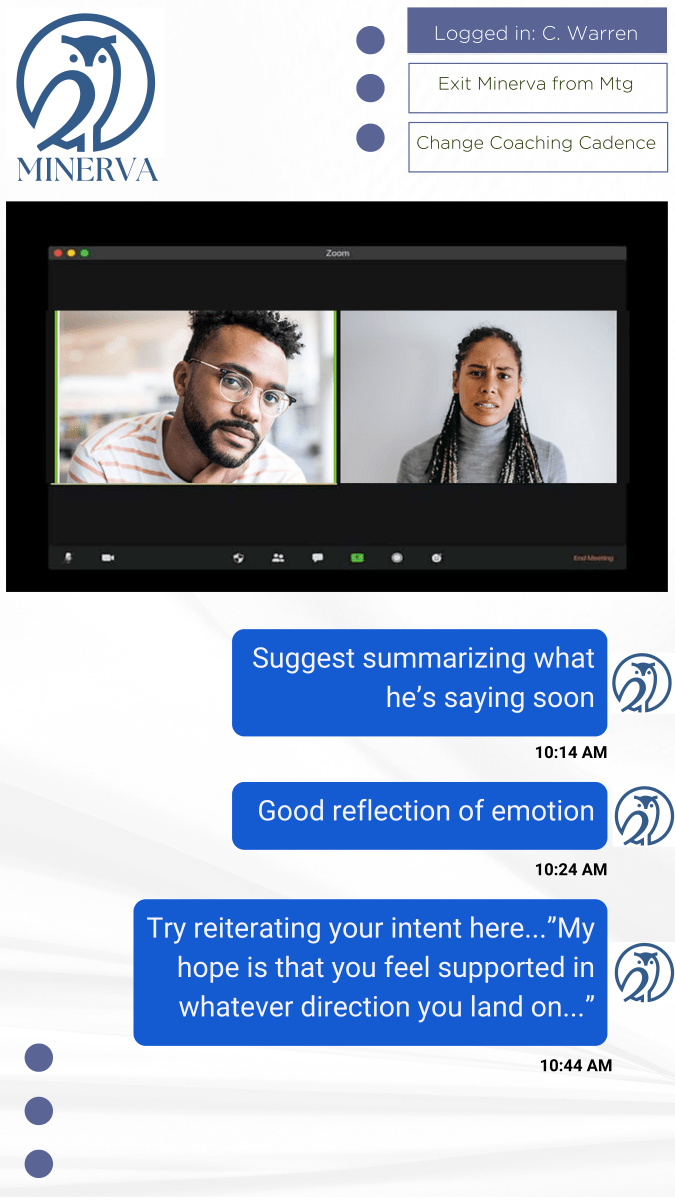

That’s the business of Kelly Kinnebrew, a psychologist in Boulder. She’s a conversation coach who helps executives find the right words under pressure. She helps leaders build trust with their audience, remember to listen and, when needed, wrap it up. But Kinnebrew doesn’t always listen in anymore. She uses artificial intelligence technology to generate texts that pop up as the conversation progresses.

“I’d tried a low-tech solution and it worked really well using an earpiece and an iPhone and giving people real-time feedback,” said Kinnebrew, who cofounded Minerva Research in 2018 to provide tech-based coaching. “AI was solidly coming into the horizon and I thought, ‘Can’t AI do this?’”

It can, apparently, especially today’s AI, which can generate a response seemingly on its own. That’s called generative AI, which became a smashing success in late 2022 when San Francisco lab OpenAI unleashed the ChatGPT-4 chatbot to the public. Companies suddenly had access to gobs of data to supplement their own niche AI systems and really expand. Like at Minerva, which anticipates releasing version 2.0 of its AI system in June.

But Kinnebrew is torn.

For the first time in her life, she sat through an hours-long committee hearing at the state Capitol late last month to testify against a bill aimed at protecting consumers from the potential harms of AI. At her business, she follows other state laws that protect consumer data and, as a psychologist, she’s bound by patient confidentiality and other ethics. But if Senate Bill 205 passes as is, companies that develop AI would have to disclose all the possible content used to train their AI and share why the AI responds the way it does. She’s not even sure that can be done. This challenges small businesses like hers that are still figuring out how to build an accurate system. The bill has undergone several changes since she testified about 10 days ago. There’s still confusion.

“Do I have interest as a consumer? Yes, absolutely I want to be protected,” she said. “So on its face, I don’t have endless criticism with the bill, even as it’s written now. But for startups that are trying to figure something out, I don’t know how they do it financially. … People in our AI community want the right legislation that protects consumers.”

National trend to regulate AI

A handful of state legislative proposals nationwide this session, including Colorado’s Senate Bill 205, has the lawmaking world trying to keep up with the latest in technology, even as tech companies are still trying to figure it out themselves. Even Big Tech is fumbling with AI, as evidenced when Google apologized in February for historical inaccuracies in its updated AI system Gemini.

The push to regulate is likely connected to the sluggishness of governments to put guardrails on Big Tech. The U.S. still doesn’t have a national data-privacy law requiring companies to provide more transparency on how consumer data is used, stored and sold (Colorado has a law).

One of the top consumer data privacy laws, Europe’s General Data Protection Regulation, went into effect in 2018 and that came too late in the opinion of Stephen Hutt, an assistant professor of computer science in the University of Denver’s Daniel Felix Ritchie School of Engineering and Computer Science. That was the same year as the Cambridge Analytica data scandal, which exposed how Facebook’s user data is used in unintended ways.

“GDPR passed relatively recently and in the lifespan of the internet, relatively late,” Hutt said.

As for AI though, it’s still early, he said. There’s a lot of venture capital going into the AI industry so it’s difficult to tell what is real and what isn’t. “Right now, you can’t look at a new tech product without it sort of throwing the word AI at you (and) knowing what that means,” he said.

If you don’t involve the right stakeholders in the conversation about regulating AI, he said, “the risk is you end up with either toothless legislation or legislation that can’t be enacted or enforced. And it’s like, ‘Well, good job us. We legislated on AI.’ And actually, it doesn’t really impact or shape the way we move forward.”

There’s actually a law like that already. New York City passed an AI hiring law in 2021 requiring employers that use chatbots, resume scanners or keyword matches to help with hiring to audit the results for possible race or gender bias and share them online. The law went into effect last year but just 18 of 400 employers had posted results, according to a Cornell University report. The Society for Human Resource Management called it “a bust.”

There are efforts to address AI at the national level, but that’s mostly from President Joe Biden’s executive order last fall to set new standards for AI safety in terms of Americans’ privacy, security and to advance equity and civil rights. A recent update noted that many of the actions taken so far were guidance to federal contractors and agencies, such as to the housing department to prohibit discrimination when using AI to screen tenants.

Others who represent the tech companies said laws need to focus on harms to consumers rather than the tools because there are bad actors in every niche, industry and technology.

“Rather than creating regulations that create so much liability that no one would be willing to create an AI tool that can be used in lending, we should look at the specific harm, which is we don’t want lenders to discriminate,” said Chris MacKenzie, senior director of Chamber of Progress, a progressive tech-industry coalition that counts Google and Meta as financial partners. The organization has also testified against the bills in Colorado and Connecticut.

Colorado’s proposed AI bill has changed since it went to committee on April 24. According to sponsor and Senate Majority Leader Robert Rodriguez, the bill is more narrow. It no longer addresses synthetic data, or data generated by an AI system that seems real but isn’t, like “deepfakes” that can manipulate a person’s likeness to make it seem like they’re doing something they did not do. It focuses on “high-risk” systems that decide who gets a loan, a house or apartment, a job or other life-impacting decision.

“This bill has been narrowed down to just discrimination and consequential high risk artificial intelligence systems,” Rodriguez testified last week. “Disclosure of an artificial intelligence system to a consumer. That’s what this bill does. That’s the law of this bill. If you’re interacting with a high-risk decision making tool, they just need to tell you.”

Companies will also have to explain any discrimination that may occur and fix it. As the bill was approved by the Senate on Friday, it would go into effect in February 2026. It passed a House committee on Saturday and heads to the main House floor on Tuesday. It also needs the Governor’s blessing. And Colorado’s legislative session ends Wednesday.

Consumer advocates say the proposals still don’t go far enough to protect consumers by allowing loopholes for companies. The Colorado bill, in particular, exempts trade secrets. But that gives companies a place to hide. Rodriguez said the bill was also influenced by a similar bill in Connecticut, which had received feedback from HR-technology company Workday. Workday currently faces a proposed class action lawsuit by the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission for violating anti-bias laws after its AI software allegedly discriminated against job applicants. The company denies allegations and said the lawsuit has no merit.

A Workday spokesman said the company has engaged with lawmakers in Connecticut, New York, California, Maryland and Washington state but not Colorado. It has not taken a position on the Colorado bill.

There are good reasons that guardrails on AI are needed now. Decisions that impact people’s lives are already being made by AI — including background checks and resume screening and adjusting auto insurance premiums, said Grace Gedye, AI policy analyst with Consumer Reports.

“It is crucial to get it right so if there’s not enough time to deliberate and create a really strong, usable bill, it’s (still) important that we get to that point,” said Gedye, who is following AI bills in Colorado, Connecticut and California and feels they need even stronger language to protect consumers though a national one would be “awesome.” “The industry groups are saying we don’t want a patchwork (of state laws) and I hear that. But it feels like the alternative may be waiting, literally decades and that just doesn’t feel fair to consumers who are being harmed in the meantime.”

How Colorado AI companies are using AI

At Minerva, human touch is still required to make its AI system work. Humans, mostly Kinnebrew, tag or label the data, whether it’s from OpenAI, another external source, or client conversations.

But it’s not the personal details of the conversation that Minerva cares about. It’s about identifying rambling, interruptions or open-ended questions. It’s about determining whether the client is listening and providing prompts that could influence the conversation or settle conflict effectively. Minerva’s AI system looks for those labels and prompts the client to, for example, ask open-ended questions or summarize what they’ve heard. Those are valued active listening skills that can be improved with coaching and set leaders apart.

“It’s about paying attention. If you get through X amount of minutes without summarizing, it will pop up something that says you probably want to summarize pretty soon,” Kinnebrew said.

Kinnebrew has put in countless hours to labeling data so that Minerva’s AI system is at the point where her “bible of prompts” is using AI to, essentially, train AI or fresh data from OpenAI and other sources. She couldn’t have reached this stage without OpenAI’s technology, she said.

“We just couldn’t go out and build it, or we could, but it would just take a long, long time and the accuracy would be quite low,” she said. As for regulations, she’s hoping that small companies like hers are exempt until they reach a certain size or revenue.

But how Minerva has labeled and trained its data is very different from the prompts that Ala Stolpnik needs, even if her company uses the same raw data.

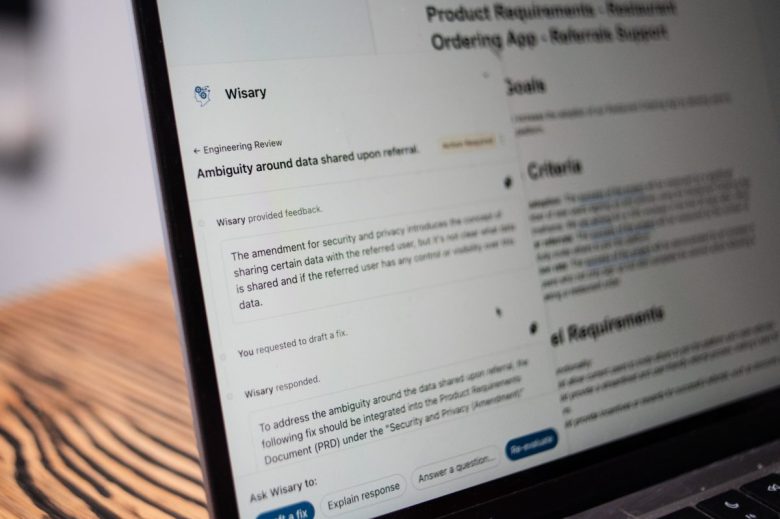

At her old job, Stolpnik often acted as the interpreter between the product team and the engineers building the product. Otherwise, things could get lost in translation.

Now, as the founder of Boulder-based startup Wisary, she’s using generative AI to help different teams at the same companies collaborate in the language each understands best. At least that’s the idea behind Wisary, which is less than a year old.

Wisary’s AI needs to determine the questions that the various teams need answered in order to build a successful product. Wisary uses documents, like Google Docs, project management systems and other professional data. She doesn’t share customer data or documents with other customers though. That could violate confidentiality agreements.

The trained AI system helps make sure no features or questions go unnoticed. It’s much like having someone like Stolpnik sitting side by side with product teams and engineers, except she would have to recall all potential possibilities immediately like a computer. But humans can’t remember everything all the time.

“What happens in reality many times is you’ll tell me that you want an ecommerce platform,” she said. “And I’ll go and build that. And then the moment I show it to you, you’re like, ‘Oh, no. It also needs this and this and that.’ And the engineers will be like, ‘You didn’t tell us that.’”

Kyle Shannon, CEO of video company Storyvine, added OpenAI’s technology in early 2023 to add transcription to videos.

“We have an app where someone answers questions in the app, it goes up to the cloud and five minutes later, you’ve got a fully edited video,” said Shannon, who cofounded Storyvine 12 years ago. “For 11 and a half years of our company, we didn’t have transcription because the transcription sucked, quite frankly. All of a sudden this thing comes out from OpenAI where it’s good enough to use and so we put transcriptions into the system.”

A more recent Storyvine product provides translation into “70 languages and 150 dialects,” he said. “And it’s insane. It’s your voice. It resyncs your lips to the words.”

The list goes on. Storyvine’s new “AI authenticity engine” takes the user’s real story, transcribes it, adds a description, shares key talking points, generates a blog post, hashtags, Instagram posts “in about a minute and a half,” he said.

The Rocky Mountain AI Interest Group was started last year after ChatGPT-4 launched and it’s now 1,435 members strong. It’s certainly not alone in Colorado as AI enthusiasts, technologists, startups and businesses already using earlier iterations of AI have formed communities.

“Our members have a wide range of reactions to the bill,” said group cofounder Dan Murray on Friday after the bill passed the Senate. “Most of them are still against it, but there are a few members who now are in favor of the new bill as amended.”

But not all AI startups or companies may even be impacted by the current statehouse proposals, even those where consumer advocates are pushing for more transparency.

“Consumer Reports’ official position is that uninterpretable and unexplainable AI should not be used for these high-stakes decisions,” said Gedye, with the consumer publication that has helped generations of Americans decide what to buy — from soup to nuts. “It’s pretty dystopian to think that technology that no one understands is making recommendations or executing decisions in these very high-stakes scenarios. It’s not like how your spam gets filtered out of your email but do you get the job, do you get a home loan or do you get a spot in college.”

Colorado’s AI bill, sponsored by Denver Democrat and Senate Majority Leader Robert Rodriguez, passed the Senate on Friday and heads to the House floor on Tuesday. Colorado’s legislative session ends Wednesday.