Aspirations and disappointments of digital education – The Mail & Guardian

Many from low-income households or rural areas lacked access and digital devices appropriate for learning

World Telecommunication and Information Society Day is celebrated annually on 17 May. This year’s theme “digital innovation for sustainable development” emphasises the importance of digital solutions to address major global challenges and to accelerate progress in key areas. One such area is education.

The UN has identified 17 sustainable development goals of which quality education is the fourth. This aspiration calls for inclusive and equitable education and the promotion of lifelong learning opportunities for all.

The fundamental underpinning of this goal is to foster constructive transformation by highlighting the power of education when aiming to contribute to a sustainable and equitable world. The goal’s premise emphasises education’s transformative capacity to drive positive change, ultimately propelling progress towards a sustainable and equitable global society.

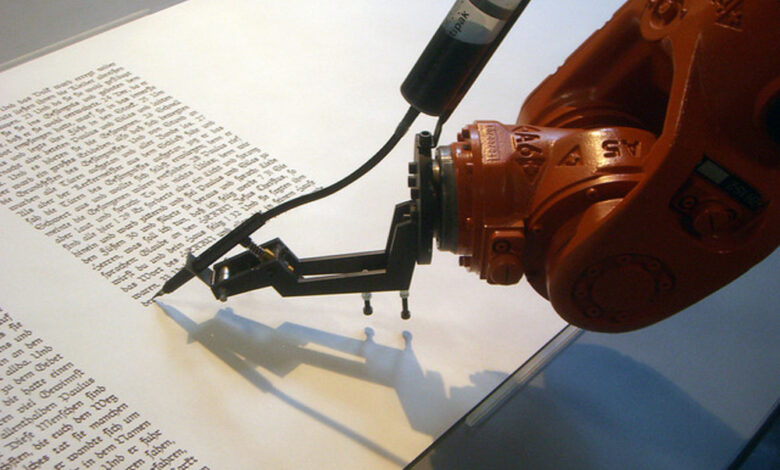

Digital education is frequently lauded as the main driving force in modernising educational systems. It holds the promise of ensuring equitable learning opportunities for all and equipping school-based learners and students with the necessary skills to thrive in the professional world.

Many examples in our recent history speak to this. For example, the Massive Open Online Course (MOOC) movement gained momentum in the early 2010s and can be traced back to Stanford University’s offer of free online courses in 2011. This movement held the promise of democratising education — rendering it accessible to individuals regardless of their geographical location, socioeconomic status or financial constraints.

At the same time, it aspired to achieve scalability, enabling the delivery of educational content to vast numbers of students simultaneously. Furthermore, MOOCs were envisioned as an affordable and flexible alternative to traditional educational models, accommodating diverse student needs and schedules.

Despite the initial enthusiasm, the movement has failed to sustain its momentum and meet the lofty expectations it had set. Low completion rates were observed across various MOOC offerings which cast doubt on the effectiveness of the learning experience.

Moreover, MOOC providers grappled with the challenge of establishing sustainable revenue streams.

Compounding these issues was the lack of widespread credibility, and recognition for MOOC credentials, among employers and traditional academic institutions.

The massive scale of MOOCs inherently made it impossible to provide personalised support and feedback to students.

A comparable situation unfolded during the Covid-19 pandemic, where educational institutions faced an abrupt transition to online learning. Those schools and higher education institutions with the financial resources and technological infrastructure managed to pivot from conventional face-to-face instruction to remote learning with relative success.

Low-resourced educational institutions, however, experienced challenges associated with the stark digital divide among learners and students. Many from low-income households or rural areas lacked access and digital devices appropriate for learning.

Other challenges include those with learning disabilities and special needs as well as language barriers where students from non-English speaking backgrounds, or with limited language proficiency, provided many additional hurdles.

In addition, the lack of preparedness of teachers and/or lecturers and the impact online learning had on assessment practices proved to be problematic.

The contemporary educational landscape is witnessing a resurgence of interest and investment in digital learning modalities, catalysed by the rapid advancements in artificial intelligence (AI). This renewed enthusiasm for AI-driven educational solutions is propelling innovative approaches that have the potential to transform the way we teach and learn.

The integration of AI into education holds immense potential to transform conventional learning approaches. A compelling case is being made for leveraging AI to create personalised learning pathways tailored to each student’s unique needs. Intelligent tutoring systems, powered by AI, can provide real-time feedback and guidance, emulating the role of a human tutor and supporting students in their educational journey.

Additionally, AI-driven adaptive learning capabilities can dynamically adjust the content, pacing and difficulty level of learning materials based on a student’s progress and comprehension, ensuring a more engaging and effective learning experience.

Furthermore, AI large language models and generative AI (GenAI) can contribute to the creation of educational content, potentially enhancing accessibility and reducing the costs associated with content development.

While acknowledging the challenges and limitations that previous educational initiatives, such as MOOCs and the rapid transition to online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic, have faced, a critical question arises: Can this latest wave of enthusiasm surrounding AI in education genuinely contribute to achieving equitable and high-quality learning experiences for all students or will it merely perpetuate existing disparities?

The promise of AI educational technologies is undeniably captivating, but their true potential to democratise and enhance educational opportunities remains uncertain, without learning from the past.

In South Africa much is still to be done in terms of bridging the digital divide. Only with a proper, sustainable infrastructure; knowledgeable, digitally literate students and lecturers and pedagogically-sound practices could the impact of AI in education be further explored.

There are already broad recommendations on the use of AI for educational purposes, such as the consideration of ethical frameworks; lecturer training and support initiatives and the development of robust assessment practices.

However, more is needed to avoid further disillusionment with digital technology. Additional and robust steps should include efforts to mitigate biases by ensuring that AI algorithms and systems are developed with a strong focus on diversity, equity and inclusion.

This involves diverse and representative data sets, rigorous testing for bias and the inclusion of culturally responsive and inclusive pedagogical approaches. Furthermore, the development of evidence-based understanding of human-AI collaboration — especially in the local context — is vital.

To further knowledge and understanding, interdisciplinary collaboration in the educational sphere should be prioritised. Encouraging collaboration between AI experts, teaching academics, disciplinary experts, social scientist, and policymakers that are not only technology-driven, but also grounded in sound pedagogical principles and social impact considerations, should be prioritised.

To promote the quest of lifelong learning, open educational resources could be emphasised by helping to reduce costs and increase accessibility, particularly for resource-constrained institutions and communities.

Educational innovation and experimentation should be prioritised where pilot projects, sandboxes or incubating spaces are encouraged to explore novel applications by fostering an environment of responsible innovation and continuous improvement.

Students are important stakeholders and role players. By encouraging student agency and co-creation, students could be involved as active participants in the design and development of AI-mediated educational solutions and initiatives.

The rapid advancement of digital technologies, with GenAI at the forefront, has opened a world of possibilities for the educational field. However, amid this exciting technological revolution, it is incumbent upon all stakeholders — educators, lecturers, technology experts, policymakers — to constantly navigate this ever-evolving landscape with a critical eye.

We must continuously and consistently question and evaluate whether these cutting-edge innovations are truly fostering opportunities for equitable and lifelong learning, ensuring that no learner or student is left behind.

By engaging in ongoing dialogue and embracing a holistic, context-specific, inclusive approach, we can strive to learn from previous mistakes and leverage the power of AI to create equitable learning experiences and access to education for all.

Dr Sonja Strydom is the deputy director of the Centre for Learning Technologies and a research associate at the Centre for Higher and Adult Education at Stellenbosch University. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the university.