What do car dealers in Congress think of EVs?

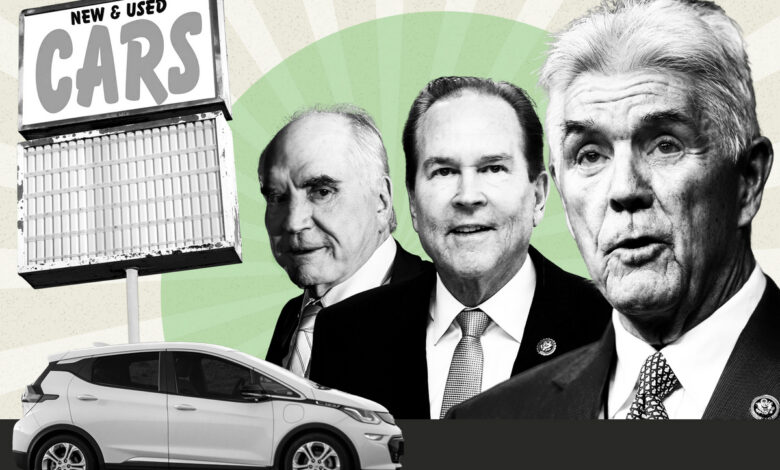

Auto dealers have powerful allies as they go to war against President Joe Biden’s electric vehicle policies: dealership owners in Congress.

The three Republican lawmakers who own car dealerships have been pushing policies, holding hearings and joining legislation to thwart the president’s drive to electrify the nation’s auto sector. They are in lockstep with increasingly vocal owners across the U.S., who say Biden’s regulatory and legislative push to rapidly electrify the nation’s auto sector is too much, too fast.

“The EV market is phony. It’s not real,” Rep. Roger Williams (R-Texas), a car dealer who chairs the House Small Business Committee, told E&E News recently.

He argued that what he dubs a “woke market” is being artificially propped up by government policies like tax credits for vehicles and grants for charging stations.

That claim may come as a surprise to the millions of EV owners across the country — and the manufacturers who make them — but the lawmakers are adamant in their stance.

In March, the administration finalized a tailpipe emissions rule, which includes a goal of half of all new vehicle sales being electric by 2030.

From his perch atop Small Business, Williams has fought against the standards, including by making it a focus of a February panel hearing slamming EPA regulations.

Williams and Rep. Mike Kelly (R-Pa.), another dealership owner, are joining dozens of colleagues in cosponsoring a Congressional Review Act resolution to overturn the rule, led by Rep. John James (R-Mich.) and Sen. Pete Ricketts (R-Neb.).

Lawmakers have also hounded Biden administration officials about the rulemaking in hearings and in a February letter to the White House Office of Management and Budget, before it was made final.

Still, Kelly said he doesn’t think the dealerships’ voices are being heard sufficiently in federal decisions about EVs.

“The dealers are almost totally unheard anymore,” Kelly said.

Williams agreed. “Guys like me need to be listened to,” he said.

The other dealer in Congress, Rep. Vern Buchanan of Florida, has been less vocal, though he thinks the Biden administration has been too aggressive in its EV push.

And the three Republicans could be joined next year by a former dealer, Republican Bernie Moreno, who is challenging Sen. Sherrod Brown (D-Ohio) in November. Moreno has said that Biden’s “manic move to electric vehicles is going to destroy the auto industry in America.”

Rep. Don Beyer (D-Va.), a former dealer himself, has even acknowledged that EV adoption is “taking longer than we had hoped.”

Indeed it’s been a tough few months for EVs. After demand surged over the previous years, automakers are scaling back plans amid disappointing sales. And dealers across the country have complained that EVs are piling up on their lots.

Tesla announced in April it planned to lay off more than 10 percent of its workforce, including in areas such as charging and policy. Ford CEO Jim Farley said in April that EVs are “a huge drag not just on Ford, but on our whole industry.”

Like ‘jet skis and motorboats’

Williams owns a dealership in Weatherford, Texas, that sells the Chrysler, Jeep, Dodge and Ram brands produced by Stellantis. But it doesn’t sell EVs.

“It’s a woke market that the Big Three bought into under Obama,” he said, referring to the former president. “They got themselves into a heck of a bind right now because nobody’s buying them. Nobody’s going to buy them.”

That’s not quite true. A record 1.2 million Amercians bought EVs last year, though the pace of sales has slowed in recent months.

Williams says he doesn’t sell EVs because he doesn’t think his customers want to buy them.

“From a dealer standpoint, it’s a just a money pit. They’ve asked us to spend money on it before anything was built. And it’s not going to work,” Williams said.

“I’m not against EVs, but what I’m for is competition. And you can’t shove this down the American peoples’ throats.”

Williams predicted earlier this year at the Washington Auto Show that EVs “won’t exist in a few years.”

Kelly said the dealerships he owns don’t sell EVs either — again, citing demand in western Pennsylvania.

“In certain markets, they were a novelty and people bought them early on. It’s the same thing for people who buy jet skis and motorboats,” Kelly said.

“Whatever you like to do — this is America, buy what you want. But the government shouldn’t have to subsidize a market that just doesn’t exist. It’s a false read that was part of a campaign.”

Kelly’s main complaints about EVs are around the federal subsidy buyers can get, which he argues isn’t necessary.

“Why would you give people $7,500 of taxpayer money to buy a car that only [the wealthy] can afford?” he asked.

Ideology, money

Environmentalists and other EV supporters have long identified car dealerships as a major hurdle to widespread EV adoption. They’ve argued that dealerships are not working to sell EVs, due to issues like ideological opposition and supply chain issues.

In general, dealers and their advocates align themselves with Republicans. In 2022, car dealers donated 4-to-1 to congressional Republicans compared with Democrats, according to OpenSecrets.

A survey the Sierra Club released last year found that only 34 percent of car dealerships had EVs available. Out of the remaining 66 percent without availability, 44 percent said they would sell EVs if the cars were made available to them by manufacturers.

“The expense necessary to prepare for EV sales is difficult for dealers to absorb,” said Sam Fiorani, vice president for global vehicle forecasting at AutoForecast Solutions, a market research firm.

“Each new EV sold today is more expensive to the dealer than one of their legacy products, but that will change in the next few years and dealers not prepared will be losing more money later,” he said. “It’s an unprecedented market shift that will cost money on all levels until things begin to stabilize, probably after 2030.”

Buchanan, the Florida Republican, has a slightly less negative take on EVs, but said they generally haven’t sold well in the dealerships that he has stakes in.

“It’s taking a little longer to get where they want to go,” he said of Biden’s expectations.

“I think the market should make that decision, not the government,” Buchanan continued. “I think that’s a big part of the problem. They pushed it out there very aggressively. The market’s not there yet, I think, across the country — I know, at least, in Florida.”

Cox Automotive, which provides software to dealerships and gathers data about their operations, found that enthusiasm for EVs among dealers is falling.

In the first-quarter update to its dealer sentiment index, just 42 percent of dealerships said their EV sales are getting better, a drop of six points and the lowest since Cox started asking the question in 2021.

Just 36 percent of dealers in the Cox report expected the EV market to improve in their areas in the following three months.

Erin Keating, a Cox analyst, said there’s plenty of room for optimism on dealerships’ involvement with EVs. In particular, manufacturers are doing more to help dealers with the issue, including pushing to slow down aggressive EV policies, better allocating vehicles to geographic areas where sales make sense and helping them buy equipment like chargers.

“Some of the hardliners, it might be a little bit more politically aligned. It also might be that their particular area or constituency may not be as interested,” Keating said.

“So [manufacturers] are thinking constructively about which regions they roll this out to and how they’re made strategic allocation and their requirements around what dealers have to do.”

And while dealerships may have feared that EVs, which require less maintenance due to simpler parts, could reduce their service income, that hasn’t been shown to be the case, said Geoff Pohanka, chair of Pohanka Automotive Group in the Washington area. He said the idea rests on “false fears.”

“EVs need repairs too. They burn tires more frequently,” Pohanka said, noting that even with a sharp increase in EV sales, the current combustion engine cars will stay on the road for a while. “We have time to adjust for that.”

Decrying a ‘mandate’

A coalition of thousands of dealerships — dubbed “EV Voice of the Customer” — sent a pair of letters to the Biden administration in November and January complaining about his EV push.

“Today, the supply of unsold BEVs (battery electric vehicles) is surging, as they are not selling nearly as fast as they are arriving at our dealerships — even with deep price cuts, manufacturer incentives, and generous government incentives,” they said in November.

“With each passing day, it becomes more apparent that this attempted electric vehicle mandate is unrealistic based on current and forecasted customer demand.”

In January, the plea was more urgent.

“It is uncontestable that the combination of fewer tax incentives, a woefully inadequate charging infrastructure, and insufficient consumer demand makes the proposed electric vehicle mandate completely unrealistic,” they said. “On behalf of our customers, we ask that you pause on the electric vehicle mandate.”

After the rule was published in March, the dealer coalition updated its website to acknowledged the standards were “softened” but said the rule still requires an EV transition that “is far beyond the consumer interest we are experiencing at our dealerships.”

None of the dealers the lawmakers own signed on.

The National Automobile Dealers Association, the industry’s main trade group, has also pushed back against Biden’s EV agenda.

The group said in comments on EPA’s proposal last year that the standards “are premised on overly aggressive assumptions regarding future EV market penetration” and they disregard “critical demand‐side marketplace factors” against EVs.

NADA didn’t respond to requests for comment, but its President Mike Stanton told the Washington Post in November that the EV transition, with Biden’s goals, “is going way too far.”

Regional differences

Not all lawmakers with ties to the auto dealer industry are so down on EVs.

Don Beyer, the Virginia Democrat, sold his interests in 2019 in a chain of northern Virginia dealerships to his brother, Michael Beyer. They sell Volvo, Subaru, Hyundai, Land Rover and other brands.

The member of Congress said he’s sympathetic to dealers having trouble selling EVs, but he supports what the Biden administration is doing.

He further applauded EPA’s decision to dial back some parts of its tailpipe regulation, arguing it was a smart move to help the industry.

“I don’t think this is an anti-environment piece at all on their behalf. I think they’re just closer to the market, and understand it’s taking longer than we had hoped to get the upturn,” he said of dealerships.

Beyer attributed some of the reluctance to EVs on regional differences. At his family’s dealerships in the wealthy, progressive Washington area, “every EV we get is gone,” but he recognized that’s not the case in other areas.

“I think what the Biden administration has just done in terms of lengthening the phase-in time is a responsible thing to do. They’re responding to what the market uptake is,” he said. “And we still want it to go as fast as possible.”