US antitrust enforcer says ‘urgent’ scrutiny needed over Big Tech’s control of AI

Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

The top US antitrust enforcer will look “with urgency” at the artificial intelligence sector, following concerns that power over the transformative technology is being concentrated among a few deep-pocketed players.

Jonathan Kanter said in an interview with the Financial Times that he was examining “monopoly choke points and the competitive landscape” in AI, encompassing everything from computing power and the data used to train large language models, to cloud service providers, engineering talent and access to essential hardware such as graphics processing unit chips.

Regulators are concerned that the nascent AI sector is “at the high-water mark of competition, not the floor” and must act “with urgency” to ensure that already dominant tech companies do not control the market, Kanter said.

“Sometimes the most meaningful intervention is when the intervention is in real time,” he added. “The beauty of that is you can be less invasive.”

Kanter, now in his third year at the Department of Justice, has alongside the Federal Trade Commission spearheaded a tougher antitrust approach, suing tech giants such as Google and Apple for what the US government alleges are unfair monopolies in services including app stores, search engines and digital advertising. He has worked closely with the FTC’s chair Lina Khan.

He said the regulators were looking at the generative AI sector and examining the competitive landscape in microchips.

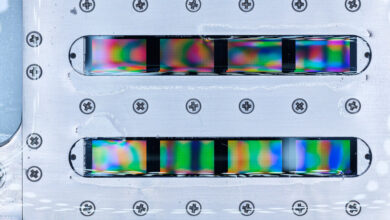

Kanter said the GPUs needed to train LLMs had become a “scarce resource”. Nvidia dominates sales of the most advanced GPUs, and its market capitalisation surged past Apple’s on Wednesday to become the world’s second-most valuable listed company.

Kanter pointed to government initiatives to boost domestic production, including the $39bn of incentives in the Chips Act, but added that antitrust regulators were looking at how chipmakers decide to allocate their most advanced products amid rampant demand.

“One of the things to think through is conflict of interest, a thumb on the scale, because they fear enabling a competitor or are helping to prop up a customer,” Kanter said. “If decisions are being made that show companies are not caring about maximising profitability or generating shareholder value, but more looking at the competitive consequences” then that would be an issue.

Since the sensation surrounding the release of OpenAI’s ChatGPT chatbot in November 2022, an arms race has broken out as companies rush to secure multibillion-dollar partnerships with some of the most promising AI companies and those building models and apps based on the technology.

Emblematic of such deals is Microsoft’s $13bn investment in OpenAI, which came with exclusive rights to the start-up’s intellectual property and a share of its profits but stopped short of an outright acquisition.

Nevertheless, the FTC as well as UK and EU competition watchdogs have said they will probe the relationship alongside Google and Amazon’s multibillion deals with rival Anthropic.

In March, Microsoft chief executive Satya Nadella hired Mustafa Suleyman, founder of another AI start-up called Inflection, and most of its 70-person staff to create a new consumer AI unit. Some industry observers saw the deal as a tactic to circumvent antitrust laws and escape a formal probe.

“Acqui-hires are something that antitrust enforcers” will look at, Kanter said, while declining to comment on any specific transactions. “We’re not using stylistic or formalistic characteristics of how these companies [explain these deals]. What we look at are the market realities.

“We are focused on the facts. If the form is different but the substance is the same, then we will not hesitate to act,” he added. “We look at what are the raw materials to produce a product. Whether that’s steel or engineers, that fits within the traditional paradigm of what we care about.”

Microsoft has pushed back against accusations that it exerts unfair influence or de facto control through its investments and cloud computing services. It has also invested in France’s Mistral and put $1.5bn into Abu Dhabi AI group G42.

“The partnerships that we’re pursuing have demonstrably added competition to the marketplace,” the tech giant’s president Brad Smith told the FT. “I might argue that Microsoft’s partnership with OpenAI has created this new AI market” and without its help, the start-up “would not have been able to train or deploy its models”.

Asked why Microsoft did not buy Inflection, he said: “We didn’t want to own the company. We wanted to hire some of the people who worked at the company.”