AI hype is deflating. Can AI companies find a way to turn a profit?

It’s not the only case of AI hype coming back down to Earth. After 11 months of public testing, Google’s AI search tool still constantly makes mistakes and hasn’t been released to most people. New scientific papers are undermining some of the flashier claims about the tech’s capabilities. The AI industry is also facing a growing wave of regulatory and legal challenges.

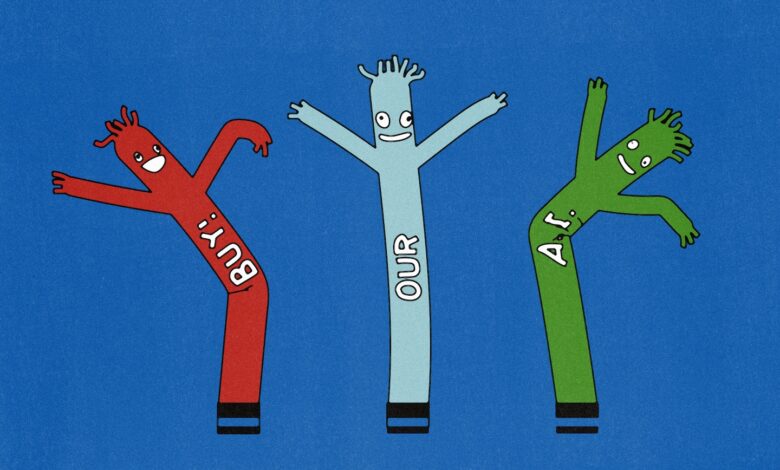

A year and a half into the AI boom, there’s growing evidence that the hype machine is slowing down. Drastic warnings about AI posing an existential threat to humanity or taking everyone’s jobs have mostly disappeared, replaced by technical conversations about how to cajole chatbots into helping summarize insurance policies or handle customer service calls. Some once-promising start-ups have already cratered and the suite of flashy products launched by the biggest players in the AI race — OpenAI, Microsoft and Google — have yet to upend the way people work and communicate with each other. While money keeps pouring into AI, very few companies are turning a profit on the tech, which remains hugely expensive to build and run.

The road to widespread adoption and business success is still looking long, twisty and full of roadblocks, say tech executives, technologists and financial analysts.

“If you compare a mature market to a mature tree, we’re just at the trunk,” said Ali Golshan, founder of Gretel AI, a start-up that helps other companies create data sets for training their own AI. “We’re at the genesis stage of AI.”

The tech industry is not slowing down its charge into AI. Globally, venture-capital funding in AI companies grew 25 percent to $25.87 billion in the first three months of 2024, compared with the last three months of 2023, according to research firm PitchBook. Microsoft, Meta, Apple and Amazon are all investing billions into AI, hiring PhDs and building new data centers. Most recently, Amazon poured $2.5 billion into Anthropic AI, bringing its total investment in the OpenAI competitor to $4 billion.

The immense cost of training AI algorithms — which requires running mind-boggling amounts of data through warehouses of expensive and energy-hungry computer chips — means that even as companies like Microsoft, OpenAI and Google slowly begin charging for AI tools, they’re still spending billions to develop and run those tools.

Google Cloud CEO Thomas Kurian said earlier this month that companies including Deutsche Bank, the Mayo Clinic and McDonald’s were all using Google’s tools to build AI applications. And Google CEO Sundar Pichai said on the company’s most recent conference call that interest in AI helped contribute to an increase in cloud revenue. But on the same call, Chief Financial Officer Ruth Porat said the company’s investment in data centers and computer chips to run AI would mean Google’s expenses would be “notably larger” this year than last year.

“We are helping our customers move from AI proof-of-concepts to large-scale rollouts,” said Oliver Parker, an executive with Google Cloud’s AI team. He pointed to Discover Financial Services as one example — the company used Google’s AI to build a tool for its call centers that reduced the amount of time it took to do each call.

Microsoft has also been trumpeting the interest in its AI tools and says 1.3 million people now use its “GitHub Copilot” AI code-writing assistant. It’s also pushing a $30-a-month AI assistant to the millions of Microsoft Office users around the world. But the company has been mum on whether any of the tools are profitable when compared with the cost of running them. Like Google, the firm has focused much of its energy on getting customers to use its cloud services to run their AI apps.

“We’re finding that AI requires a paradigm shift,” said Jared Spataro, Microsoft’s corporate vice president of AI at Work. “It’s not like a traditional technology deployment where IT flips a switch. Businesses need to identify areas where AI can make a real impact and strategically deploy AI there.”

In October, OpenAI announced its own version of the app store, where people could make their own custom versions of the popular chatbot, ChatGPT, upload them to a public marketplace, and get paid by OpenAI if many people used them. Three million custom GPTs have been created, but the company hasn’t said whether it has paid out any money yet.

“These tools are not yet pervasive, not even close,” said Radu Miclaus, an AI analyst at tech research firm Gartner. He expects that to begin changing soon. “My expectation is that this year the applications will start taking off.”

Beyond the Big Tech companies, a legion of start-ups are trying to find ways to make money with “generative” AI tech like image generators and chatbots. They include trying to replace customer service agents, writing advertising copy, summarizing doctors’ notes and even trying to detect deepfake AI images made by other AI tools. By replacing workers or helping employees become more productive, they hope to sell subscriptions to their AI tools.

Many computer programmers say they already use chatbots to help them write routine code. Usage across the rest of the workforce is also slowly increasing, according to Pew Research Center. Around 23 percent of U.S. adults said they’d used ChatGPT at work in February 2024, compared with 18 percent in July 2023, the research organization found.

“We’re at the very, very beginning,” said John Yue, founder of Inference.AI, a start-up that helps other tech companies find the computer chips they need to train AI programs. AI will work its way into every single industry, but it might take at least three to five years before people really see those changes in their own lives, he said. “We have to take a longer look.”

There are big roadblocks that could slow down the industry, too. Governments have also bought into AI hype, and politicians in the U.S. and abroad are busy debating how to regulate the tech. In the U.S., smaller AI companies have expressed worries that AI leaders like Google and OpenAI will lobby the government to make it harder for new entrants to compete.

In Europe, final details of the E.U.’s AI Act are being hammered out, and they promise to be more restrictive than companies are used to. One of the biggest concerns that Golshan, the AI data start-up CEO, hears from business clients is that new AI laws will render their investments a waste in the future. A battery of lawsuits have also been launched against OpenAI and other AI companies for using people’s work and data to train their AI without payment or permission.

Though the tech continues to improve, there are still glaring problems with generative AI. Figuring out how to make sure models that are supposed to be reliable don’t make up false information has vexed researchers. At Google’s big cloud computing conference in early April, the company offered a new solution to the problem: customers using its tech to train AI models could now let their bots fact-check themselves by simply looking things up on Google Search.

Some claims about AI’s near-magic ability to do human-level tasks have also been called into question. A new paper from researchers at the University of Massachusetts, Adobe, the Allen Institute for AI and Princeton showed that AI models routinely made factual mistakes and errors of omission when asked to summarize long documents. Another recent paper suggested that a claim that AI was better than the vast majority of humans at writing legal bar exams was exaggerated.

The big improvement in AI tech showcased by ChatGPT that kicked off the boom came from OpenAI feeding trillions of sentences from the open internet into an AI algorithm. Subsequent AIs from Google, OpenAI and Anthropic have added even more data from the web, increasing capabilities further. Seeing those improvements, some famous AI researchers moved up their predictions for when they think AI would surpass human-level intelligence. But AI companies are running out of data to train their models on, raising the question of whether the steady improvement in AI capability will plateau.

Training bigger and better AI models has another crucial ingredient — electricity to power the warehouses of computer chips crunching all that data. The AI boom has already kicked off a wave of new data center construction, but it’s unclear whether the United States will be able to generate enough electricity to run them. AI, coupled with a surge in new manufacturing facilities, is pushing up predictions for how much electricity will be needed over the next five years, said Mike Hall, CEO of renewable energy management software company Anza, and a 20-year veteran of the solar power industry.

“People are starting to talk about a crisis, are we going to have enough power?” Hall said.

Ethan Mollick, an associate professor at the University of Pennsylvania who studies AI and business, said company executives are seeing the benefits of AI to their businesses in early experiments and tests, and are now trying to work out how to work it into their organizations more broadly.

Some of them are concerned that their AI tools might be made obsolete by new tech released in the future, making them hesitant to invest a lot of money right now, he said. OpenAI is set to unveil its latest AI model in the coming months, potentially offering a whole new set of capabilities, Mollick said.

“The underlying technology drumbeat hasn’t really stopped,” he said. “It’s going to take some time to ripple through.”