Are We Doomed? Here’s How to Think About It

I was more than charmed by the students, I admit. Their temperaments were brighter than my own, their thoughts more surprising. It was a tiny, unrepresentative group, but they didn’t resemble “young people” as they are portrayed in popular culture. When I asked them whether concern about the environment or other risks was likely to affect their decisions about having families, they looked at me as if I were a pitiable doomer—no, not really.

Holz is the chair of the Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, which sets the Doomsday Clock each year. The Bulletin was founded in 1945 by scientists in Chicago who had worked on the Manhattan Project and wanted to increase awareness, they wrote, of the “horrible effects of nuclear weapons and the consequences of using them.” (The first controlled and self-sustaining nuclear chain reaction—led by Fermi—had taken place beneath what was then the University of Chicago football field and is now a library.) The cover of the Bulletin’s first issue as a magazine was a clock set at seven minutes to midnight. The time was chosen, Holz explained, largely because it looked cool. But it was a powerful image; a ticking clock is a classic narrative device for a reason. “The farthest from midnight it ever went was seventeen minutes before midnight, at the end of the Cold War,” Holz said. A humble physical version of the clock—made of what looks to be cardboard and showing only a quarter of a clock face—is kept in a corner on the first floor of a building on the Chicago campus that houses the School of Public Policy and the Bulletin. Currently, the clock shows ninety seconds to midnight, the same as last year, and the closest to midnight it’s ever been.

Holz’s days often include listening to the detailed worries and assessments of non-agreeing experts who devote their lives to thinking about biothreats, nuclear risk, climate change, and perils from emerging technologies. It must, I imagine, feel like being pursued by a comically dogged black cloud. “It’s insane that one person can destroy civilization in thirty minutes, that that is the setup,” Holz said, in passing, while we were waiting for an elevator; no one can veto an American President who decides to launch a nuclear weapon. Yet, if you ask Holz anything about astrophysics, the sun returns. “Black holes are a beacon of hope and light,” he said, visibly pleased by the wordplay. (His papers have titles such as “How Black Holes Get Their Kicks: Gravitational Radiation Recoil Revisited” and “Shouts and Murmurs: Combining Individual Gravitational-Wave Sources with the Stochastic Background to Measure the History of Binary Black Hole Mergers.”) “Cosmology is a consolation, in part because it puts a positive valence on our smallness,” he explained. The universe is magnificent and more than immense, and we’re extremely minor and less than special—and then there are all those civilizations we keep not meeting. Somehow the vast, indifferent cosmos makes Holz feel more inspired to work to give humanity its best chance. “It’s the opposite of nihilism,” he said. “Because we’re not special, the onus is on us to make a difference.”

The students also had their own emotional weather systems. When I spoke to Lawton, a graduate student in international relations and a policy wonk, he said that he was “probably one of the most optimistic people here.” He wanted to work in government, and told me that he was counting on humanity’s desire to survive—that this desire, ultimately, would steer us from disaster. He also told me that he felt pretty different from the other students at Chicago, in part because he had attended a small college in Lakeland, Florida, and was working three part-time jobs, one of which was editing videos—work that, he pointed out lightheartedly, he would presumably soon lose to A.I. As a child, Lawton thought school was fantastic in every way; home was not a great place to be. He said that it was odd to have someone ask his opinion—he hated talking about himself and generally avoided it. When I asked him his age, he replied that he was born in 2000, the Year of the Dragon. I’m a Dragon, too, I told him. That reminded me that I was twice his age. I didn’t feel two Chinese Zodiac cycles older than him—but I did grow up thinking that the microwave was the end point toward which technology had been heading for all those years.

I was curious to learn the students’ first memories of the idea of an end-time. Mikko remembered as a kid seeing a trailer for a reality-TV show on the Discovery Channel, in which contestants battled for survival in faux post-apocalyptic environments. Isaiah recalled losing electricity during Hurricane Sandy. “I remember playing Monopoly by candlelight—at first, it was kind of novel, this lack of technology, but then it was just very depressing, so I think that was kind of when I had the sense that climate change can affect everyone,” he said. He went through a phase in middle school of being very interested in preppers and going deep into related Reddit threads. “Not much happened,” he said, smiling. “I didn’t have an allowance.”

At the start of the sixth week of class, Holz announced a linked film series that would screen at the Gene Siskel Film Center: “Godzilla,” “WarGames,” “Don’t Look Up,” “Contagion.” The visiting guest that week was Jacqueline Feke, a philosophy professor at the University of Waterloo. She guided students through the etymology of “utopia,” a word invented by the philosopher and statesman Thomas More, who was decapitated for treason. “Utopia” is the title of More’s book, from 1516, about an imagined idyllic place—speculative fiction, we might say today. More’s neologism suggested a place (from the Greek topos) that is nowhere (from the Greek ou, meaning “not”). The readings, which included E. M. Forster’s “The Machine Stops” and excerpts from Plato’s Republic, were less harrowing than those of other weeks, when students read chapters from “The Button: The New Nuclear Arms Race and Presidential Power from Truman to Trump,” by William J. Perry and Tom Z. Collina, and “The Uninhabitable Earth,” by David Wallace-Wells.

Imagining utopias, imagining dystopias—how do we get to a better place, or at least avoid getting to a much worse one? During the discussion, Mia, a graduate student in sociology who had experience in the corporate world, brought up “red teaming,” a practice common in tech and national security, in which you ask outsiders to expose your weaknesses—for example, by hacking into your security system. In this manner, red teaming functions like dystopian narratives do, allowing one to consider all the ways that things could go wrong.

But hiring people to hack into a system also lays out a road map for breaking into that system, another student argued. Thinking through how humans might go extinct, or how the world might be destroyed—wasn’t this unreasonably close to plotting human extinction?

“Yeah, it’s like ‘Don’t Create the Torment Nexus,’ ” someone called out, to laughter. This was a meme referring to the idea that if a person dreams up something meant to serve as a cautionary tale—for example, Frank Herbert’s small assassin drones that seek out their targets, from “Dune,” published in 1965—the real-life version will follow soon enough.

“Like, there’s a way that dystopian fiction is a blueprint—”

“It can be aspirational—”

“We’ll end up having a Terminator and a Skynet,” someone else said, in reference to the Arnold Schwarzenegger movies. The discussion was cheerfully derailing, with students interrupting one another.

“So are we thinking that we need to regulate dystopian fiction?” Holz asked sportively.

Evans pushed the logic: “Plato’s Republic says we can’t play music in minor keys because it’s too painful—do we want that?”

No, nobody wanted that, though the students had trouble articulating why.

“Maybe we need to stop teaching this class right now,” Evans proposed. The class laughed. “But we won’t.”

H. G. Wells, in his essay “The Extinction of Man,” writes of the possibility that human civilization might be devastated by “the migratory ants of Central Africa, against which no man can stand.” Wells chose an example that would be difficult to imagine, in part to point out the feebleness of human imagination. Although the term “existential risk” is often attributed to a 2002 paper by the philosopher Nick Bostrom, there is a long, unnamed tradition of thinking about the subject. Among the accomplishments of the sixteenth-century polymath Gerolamo Cardano is the concept that any series of events could have been different—that there was chance, there was probability. It was an intimation—in a time and place more comfortable with fate and God’s will—of how unlikely it was that we came to be, and how it’s not a given that we will continue to be. (Cardano’s mother supposedly tried to abort him; his three older siblings died of the plague.) A more modern formulation of this thinking can be found in the work of the astrophysicist J. Richard Gott, who argues that we can make predictions about how long something will last—be it the Berlin Wall or humanity—on the basis of the idea that we are almost certainly not in a special place in time. Assuming that we are in an “ordinary” place in the history of our species allows us to extrapolate how much longer we will last. Brandon Carter, another astrophysicist, made an analogous argument in the early eighties, using the number of people that have existed and will ever exist as the expanse. These and similar lines of thought have come to fall under the umbrella of the Doomsday Argument. The Doomsday Argument is not about assessing any particular risk—it’s a colder calculation. But it also prompts the question of whether we can steer the ship a bit to the left of the oncoming iceberg. The biologist Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, “Silent Spring,” for example, can be said to grapple with that question.

Jerry Brown, the two-time governor of California and three-time Presidential candidate, was set to speak to the class on a winter afternoon. One student was eating mac and cheese and another was drinking iced tea from a plastic cup with a candy-cane-striped straw. Holz entered the classroom while on a phone call. Brown’s voice could be heard on the other end, asking if “this generation” would know who Daniel Ellsberg was, or would he need to explain? Holz said that the students would know.

When Brown’s face was projected onto the classroom screen, he was red-cheeked and leaning in to the camera. “I don’t see the class,” he said, his voice on speaker. “There’s no audio here.” One of the T.A.s adjusted something on a laptop. Then Brown got going. He had plenty to say. “You’re young. The odds of a nuclear encounter in your lifetime is high,” he told the students. “I don’t want to sugarcoat this.”

Brown, eighty-six years old, spoke with the energy of someone sixty years his junior who has somehow had conversations with Xi Jinping and is deeply knowledgeable about the trillions of dollars spent on military weapons globally. “We’re in a real pickle,” he said. He brought up Ellsberg, a longtime advocate of nuclear disarmament. Ellsberg, who died last June, thought that the most likely scenario leading to nuclear war was a launch happening by mistake, Brown said. There are numerous examples of close calls. In June, 1980, the NORAD missile-warning displays showed twenty-two hundred Soviet nuclear missiles en route to the United States. Zbigniew Brzezinski, Jimmy Carter’s national-security adviser, was alerted by a late-night phone call. Fighter planes had been sent out to search the skies, and launch keys for the U.S.’s ballistic missiles were removed from their safes. Brzezinski had only minutes to decide whether to advise a retaliatory strike. Then he received another phone call: it was a false alarm, a computer glitch—there were no incoming missiles. In 1983, a Soviet early-warning satellite system reported five incoming American missiles. Stanislav Petrov, who was on duty at the command center, convinced his superiors that it was most likely an error; if the Americans were attacking, they wouldn’t have launched so few missiles. In both instances, only a handful of people stood between nuclear holocaust and the status quo.

“A world can go on for thousands of years, and then all hell can break loose,” Brown observed. Nonlinear. He spoke of the Gazans, the Ukrainians, the Jews in Germany in the nineteen-thirties. He spoke of the Native Americans. It wasn’t just a matter of worst fears being realized—it was a matter of catastrophes that had not been foreseen. It was only luck, Brown said, that we had gone seventy-five years without another nuclear bomb being dropped in combat.

The conversation shifted to student questions. What about the nuclear-arms package that Congress had passed? Was there a way to talk about nuclear disarmament without quashing nuclear energy? What did Brown think about the idea that with existential risk there’s no trial and error? How can predictions be made if they aren’t based on events that have happened? The time passed quickly, and Holz asked Brown if he was up for five more minutes. “I’m up for as long as you want,” he said. “We’re talking about the end of the world.”

Nuclear destruction had also been the topic of the first class of the term, when Rachel Bronson, the C.E.O. and president of the Bulletin, was the guest lecturer. In that first class, more than half the students had listed climate change as their foremost concern. By the end of the course, nuclear threats had become more of a concern, and students were speaking about climate change as “a multiplier”—by increasing migration, inequality, and conflict, it could increase the risk of nuclear war.

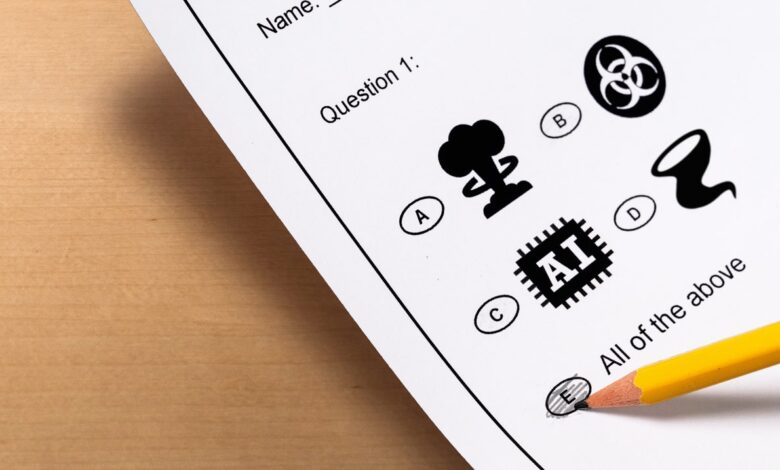

Toby Ord, who has systematically ranked existential risks, believes that A.I. is the most perilous, assigning to it a one-in-ten chance of ending human potential or life in the next hundred years. (He describes his assessments as guided by “an accumulation of knowledge and judgment” and necessarily not precise.) To nuclear technology, he assigns a one-in-a-thousand chance, and to all risks combined a one-in-six chance. “Safeguarding humanity’s future is the defining challenge of our time,” he writes. Ord arrived at his concerns in an interesting way; as a philosopher of ethics, his focus was on our responsibility to the most poor and vulnerable. He then extended the line of thinking: “I came to realize . . . that the people of the future may be even more powerless to protect themselves from the risks we impose.”

“I think about the Fermi paradox literally every day,” Olivia told me near the end of the course. “When you break down the notion that it’s not going to be aliens from other planets that will be the end of us, but instead potentially us, in our lack of responsibility . . .” But she wasn’t fearful or anxious. “I’d say I’m more interested in how we cope with existential threats than in the threats themselves.”

Finals week arrived. It’s like the world stops for finals, one student said, of the atmosphere on campus. Evans was doing downward dogs during a break in class; Holz was drinking a Coke. Both seemed discreetly tired, like parents nearing the end of their kids’ school sports tournament. The class had been a kind of high for everyone. And soon it would be over. The students had been working on their final projects; the assignment was to respond creatively to the themes of the class. In the 2021 course, a student wrote and illustrated a version of the children’s classic “Goodnight Moon” which was “adapted for doom.” (“Goodnight progress / And goodnight innovation / Goodnight conflict / Goodnight salvation.”) One group made a portfolio of homes offered for sale by Doomsday International Realty: a luxury nuclear bunker, a single-family home on the moon.

Lucy and three classmates were putting together syllabi that imagined what Are We Doomed? classes might look like at different points in time: the Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and the year 2054. The majority of Lucy’s contributions had been to the Industrial Revolution syllabus. Alexander Graham Bell was the guest lecturer on technology and society, and the readings for his week included works by John Stuart Mill, various Luddites, and Thomas Carlyle. Lucy spoke of how Carlyle wrote with alarm, in “Signs of the Times,” about what had been lost to mechanization, the decline of church power, and how public opinion was becoming a kind of police force—observations that, she pointed out, are still relevant. Everything was going to hell, and always has been. A question that came up repeatedly in class discussions was whether our current moment is distinctively risky; most experts argue that it is.

Lawton was working with two friends on a doomsday video game, in which a player makes a series of decisions that move the world closer to or farther from nuclear destruction. “You have three advisers: a scientist, a military chief of staff, and a monocled campaign manager who is focussed entirely on getting you reëlected,” he said. After facing these decisions, each with difficult trade-offs, the player receives an update on how various dangers—nuclear war, climate change, A.I., biothreats—have advanced or receded. If your decisions lead to nuclear annihilation, the screen reads “The last humans cower in vaults and caves, knowing they are witnessing their own extinction.”

Mikko, too, had incorporated a game into his final project. Holz had asked the class to think about how effective the Doomsday Clock was in drawing attention to existential risk. Mikko and his project partner wanted to develop graphics that would better communicate the idea of climate change as a progressive existential threat. “We are already knee-deep, and it’s about mitigation and adaptation,” he said. He thought that the Doomsday Clock, while effective, had a nihilistic feel: even though the time on it can be changed in either direction, our human experience is of time ceaselessly moving forward, which makes nuclear Armageddon feel like a foregone conclusion. The game Snakes and Ladders was an inspiration for one of the graphics, which included a stylized ladder. “More rungs can be added to the ladder or removed from it,” Mikko said, explaining that this made it focussed on action. With climate, he feels that it is not only counterproductive “but also a kind of cowardice” to give up. We can never go back to what we had before, he said, but that was “a prelapsarian ideal about being pushed out of the Garden of Eden.” In his own way, the nay-saying Mikko sounded like what most of us would call an optimist.

I decided to rewatch “La Jetée,” by Chris Marker, a short film from 1962 that was on the syllabus for the week of “Pandemics & Other Biological Threats.” In “La Jetée,” the protagonist is part of a science experiment that requires time travel to the past. But he must also travel to the future, so that he can bring back technology to save the present from a disastrous world war, left mostly undetailed, that has already occurred. The protagonist prefers returning to the past, where he has—as one does in French films from the nineteen-sixties—become close with a beautiful woman whom, before the time-travel experiments, he had seen only once.

I remembered being perplexed and bored by the film when I watched it years ago. Isaiah had made it sound interesting again. “What was so compelling was that the main story wasn’t exactly whatever the disaster was, or what the future was like,” he said. The way the character was stuck in the past, even as the future kept proceeding without him, reminded Isaiah of the pandemic, of how he felt stuck in a “liminal state.” He remembered feeling as if he needed to be told, as happens to the character in the film, to go to the future.

The students were so much less daunted or flattened by reflecting on the future than I was—than most people I speak with are. I wondered, Do we have less equanimity because we know or feel something that the students don’t, or because we don’t know or feel something that they do?

Mikko described a change of sentiment that he had experienced in the final weeks of the course. “I was thinking about the nature of being doomed, on a personal level and on a societal level,” he said. Being doomed is connected to a lack of autonomy, he had decided: “You’re fated to a negative outcome—you’re on rails.” On a societal level, he said, he doesn’t think we’re doomed. But, on an individual level—the majority of people probably are doomed. “And that sucks.”

He said that the course had made him think about people throughout time who believed that their world would soon end. “The last week of discussion, I wrote about the cathedral-building problem,” he said. How could people who faced such uncertain lives build cathedrals, the construction of which could go on for lifetimes? “The argument I made was that the people who built cathedrals were people who believed in Revelations, who were sure they were doomed.” He digressed for a moment: “It’s astonishing how many end-of-the-world myths there are, almost as numerous as creation myths.” Then he returned to the cathedral builders, or maybe to himself. “It’s a weird feeling—to be certain that the world will end,” he said. “But also not certain about the specific hour or day of when it will happen. So you think, I may as well dedicate myself to something.” ♦