Automobiles Cost Massachusetts About $64 Billion Every Year: Study

We like to think there’s a reason behind the way things are. And yet, in reality, our societies are shaped by arcane market forces and the maelstrom of actions by billions of individual actors. It raises the question—if we intentionally tried to change our cities, would it make a difference? A Harvard study in 2019 raises certain questions about the status quo of the automobile given the costs they incur for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Many Western societies take the car as a default. The sprawling suburbs of the United States demand vehicle ownership as the price of admission. Far-flung shopping districts mean you can’t get food if you don’t have a car. Criss-crossed highways leave no room for pedestrians. A lack of alternative transport links means you need to get behind the wheel if you want to go anywhere, or pay someone to take you.

![]()

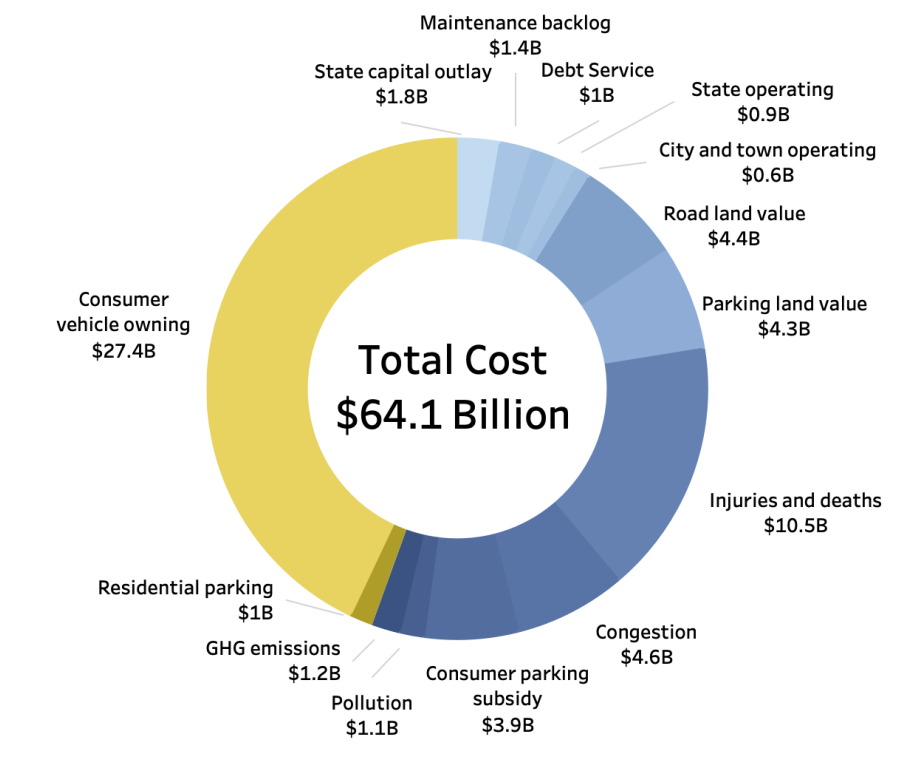

These are all very real costs for both individuals and governments alike. Cars must be fueled and repaired, licenses bought and paid for. Infrastructure must be maintained, and ever more roads built in an endless losing battle against traffic. Add it all up, and for Massachusetts, the bill apparently came to a mighty $64 billion a year. Let’s look at how it figures out.

Dollar Bills

The study was undertaken by Linda Bilmes in her role as a senior lecturer in Public Policy at Harvard, and supported by graduate students at the Harvard Kennedy School. In its conclusion, the study states that relying on cars and light trucks costs $64.1 billion a year in the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

That figure covers all the costs, both public and private, incurred in running and maintaining the 4.5 million passenger cars and light trucks that plied the state’s roads in 2019. It also takes into account infrastructure costs, such as capital costs to state authorities. Furthermore, the study measured social and economic costs from things like traffic congestion, pollution, and injuries due to road accidents. Land use impacts from parking lots was also considered. This can often be a blight on downtown areas, taking up great amounts of space and ruining walkability.

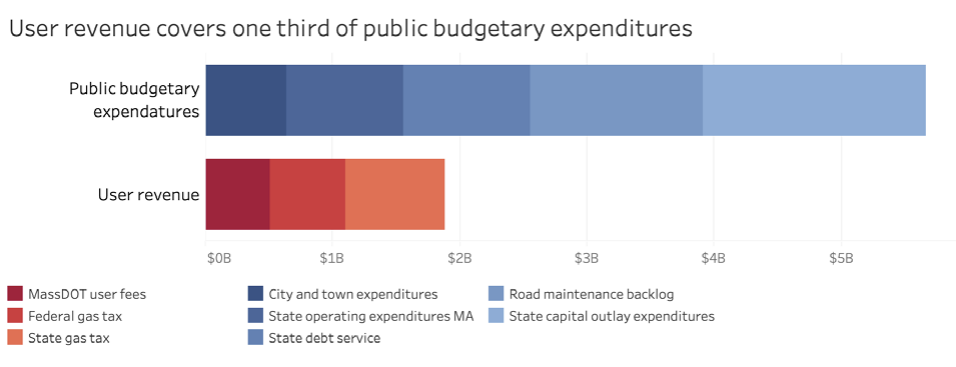

“The numbers are surprisingly high, and should make us think twice about whether cars are the most cost-effective ways to connect,” said Bilmes. As a guide, the public costs of the car economy—around $35.7 billion in total—end up costing around $14,000 per family in the state. This is irrespective of whether or not the given family owns a vehicle. That’s in part because gas taxes and infrastructure user fees aren’t enough to cover the state’s budgetary costs. In Massachusetts, they covered only a third at best in the study period. This shortfall is thus made up from other taxation revenue.

Consumer costs make up the remaining $28.4 billion of the $64.1 billion bill, or roughly 44.3%. Families that own a vehicle spend an extra $12,000 of their own money on average, in direct costs like gas and vehicle maintenance.

Beyond consumer vehicle ownership, injuries and deaths come in as particularly expensive. At an estimated $10.5 billion a year, it’s a big handbrake holding back the state. These numbers are based on the calculations of the “value of a statistical life” (VSL), based on US Department of Transport methodology. There’s a very human cost when humans are injured or killed on the roads. There’s also an economic cost due to the loss of that person’s future contribution to society. Congestion also plays a big role. In 2019, there was an estimated $4.6 billion cost for all the time the people of Massachusetts waste sitting around in traffic.

The authors were keen to note that this high cost should be taken into account when pricing out public transport projects. “Of course we need cars and roads–but we also need to remember that cars and roads are not free,” said Blimes.

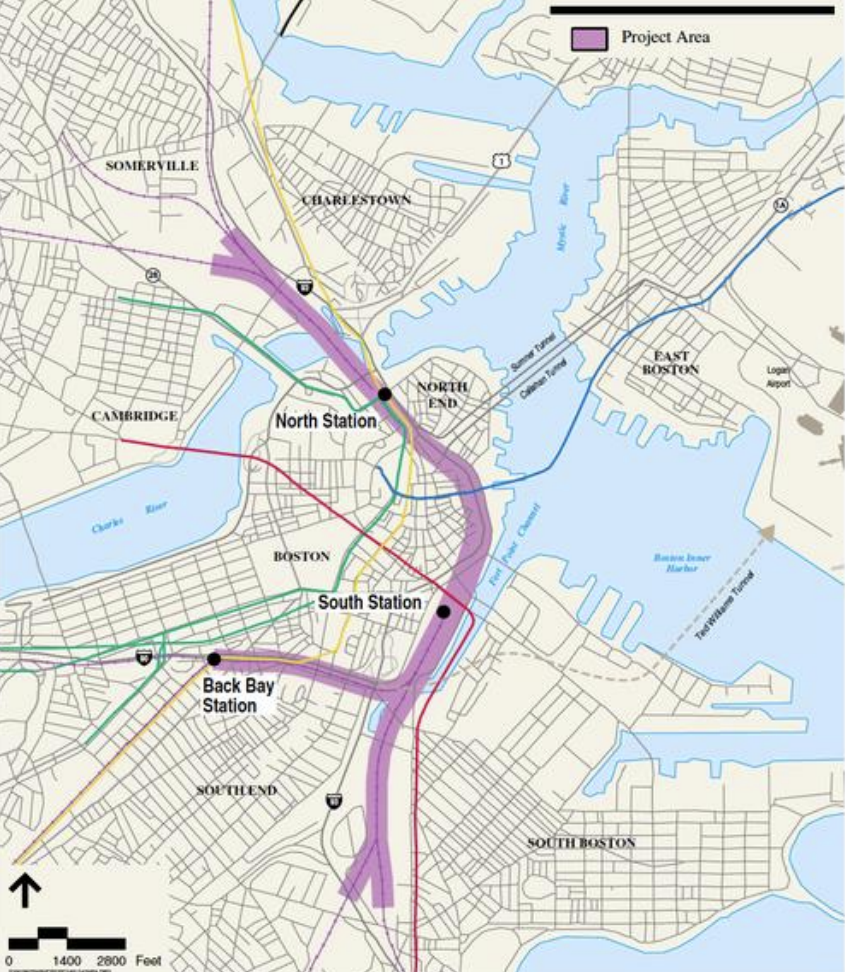

Think of it this way. The construction cost of a project like the North-South Rail Link might incur $3.8-$12.3 billion in one-off costs. In turn, it would reduce reliance on-road vehicles and help shave down that massive $64 billion that’s being spent on automobile transport every year. Suddenly, it sounds like a much more compelling deal.

Obviously, public transport projects come with their own maintenance and staffing costs. They’re not free, either. But the general assumption needs to be that these projects come with a side economic benefit. When built and utilized properly, they can cut personal and public spending on roads and vehicles significantly.

Personally, as a huge car fan, I’m picking up what the study is putting down. I love driving, but I hate commuting. In fact, a lot of my daily car trips are frustrating and dull. I yearn to live somewhere I can walk to get a coffee instead of having to drive for ten minutes and go through four traffic lights. I’d love to catch the train for a night out instead of spending huge sums on Uber rides to get home.

Cars are great, and it’s good to love them. But they come with a caveat. When we build our cities and our lives around them as a necessity, it’s costing us more than we might think.

Image credits: Harvard study, Harvard Study, Leon Bredella via Unsplash License incl. top shot