Canada – Patent – Generative AI And IP: Challenges In Protecting And Using GenAI Tools

“ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE” (AI) was the most searched topic on Wikipedia in 2023. Dictionary publisher Collins dubbed AI the most notable word of the year…

Canada

Intellectual Property

To print this article, all you need is to be registered or login on Mondaq.com.

“ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE” (AI) was the most searched

topic on Wikipedia in 2023. Dictionary publisher Collins dubbed AI

the most notable word of the year, and millions of ordinary people

gained direct access to sophisticated AI products through ChatGPT,

Midjourney, and other generative AI tools. Given the close

relationship between intellectual property (IP) rights and

technology, it comes as no surprise that AI is rapidly shaking up

the world of IP.

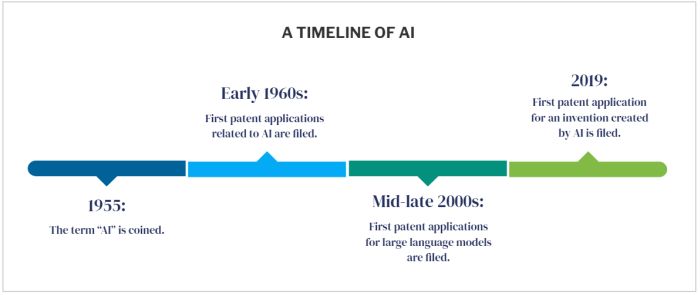

AI, however, is not new. The earliest patents relating to neural

networks, an AI method of processing data in a manner inspired by

the structure of the human brain, date back to the 1960s. Other AI

technologies, including computer vision (the identification of

objects in images and videos by computers) and natural language

processing, have been widely discussed in scientific publications

and patents for more than 50 years. According to a study by the

World Intellectual Property Office, between 1960 and 2018, 340,000

originating patent applications relating to AI inventions were

filed.

The focus of these patent applications has evolved over the

years, but the number of patent applications related to AI has

steadily increased. The majority of AI technology today involves

the use of models trained to categorize inputs into two or more

classes. These models are derived by analyzing patterns in

historical data sets and are then used to provide output

predictions by classifying a specific set of inputs. Though these

models have been refined over the years and can now make

predictions with lower error rates and based on very large data

sets, at their core, they are fundamentally very similar to the

models and algorithms first described by AI pioneers more than 50

years ago.

The latest AI boom, however, has increased access to these

models, allowing almost anyone to make use of these models with

minimal training. This has led to the proliferation of new business

offerings for services or products and a corresponding rise in AI

companies seeking patent protection for the application of AI

concepts to a wide range of technical, business, and other

problems. While some of these services are commercially valuable

and fill real gaps in the market, they may not always be

patentable. The criteria for patentability have not changed. An

invention must still be new and inventive to be patentable.

Furthermore, an invention must be described in a patent application

with sufficient detail to enable an ordinary technologist in the

field to understand and make use of it. In many cases, inventors do

not understand the models created with AI tools to sufficiently

explain how they work.

The ongoing democratization of AI tools has led to a shift in

the standard for patenting inventions that incorporate AI. Until

recently, it was typically possible to obtain a patent for a new

application of existing AI models to solve a new problem. However,

as ever-more sophisticated AI models and larger data sets become

ubiquitous, obtaining valuable patent protection merely for

applying AI techniques in a new area is more difficult. In general,

it is much easier to obtain a valuable patent for an invention that

involves an inventive, unconventional, or unexpected approach to,

for example, collecting or organizing a data set particularly

suited for making a specific tool or developing a new AI model,

which is often a refinement of an existing model.

While the underlying AI technology has been under development

for decades, the increasing availability of computing power through

both individual users’ computers and distributed computing

networks and extremely large data sets has led to the widespread

availability of large language models and other generative AI

tools. Generative AI includes algorithms that can create new

content based on training data and user prompts. These technologies

pose new IP challenges for users.

In Canada and around the world, whether the use of data to train

a generative AI model is a fair use of that data remains unclear.

Similarly, whether the output of a generative AI tool can infringe

copyright or other IP rights in the data that was used to train the

tools and what legal tests will be used to assess such an

infringement are unclear. There is often little information on the

training sets used to train the models and whether they could

include content to which IP rights attach. Then, there is also the

question of whether a generative AI model could generate the same

content multiple times in response to different inputs and whether

this could be problematic if used by different individuals. The law

is slowly adapting to these new realities as cases arise.

The rise of large language models (LLMs) has also led to the

creation of tools that will disrupt how IP firms operate. Several

AI-powered tools for drafting documents such as patent

applications, for example, have been launched in the past few

years, and many of these tools are accessible to the public. At

present, these tools can deliver only very rudimentary patent

applications of limited scope. Their output still requires

substantial revision by experienced practitioners to produce a

valuable patent application. However, given the rapid rate of

development of LLMs, in just a few years, these tools may well be

capable of generating work that, at least at first blush, appears

to have all the hallmarks of a high-quality patent application.

These tools are constrained by both the relevance of their

training data to the drafting task at hand and the extent to which

the tools can extrapolate from that training data to produce a

description of new and inventive technology. For individuals or

companies seeking to reduce costs or to rapidly build large patent

portfolios, these tools could provide an appealing alternative to

traditional law firms. However, overreliance on the tools may

introduce substantial risk that the ultimate rights obtained will

be narrow and easily designed around. Our experiments with these

tools indicate that while the output they generate superficially

complies with legal requirements for patent applications, the

applications are narrow and of limited value. However, the

differences between a document generated by these tools and a

document prepared by an experienced practitioner may not be

immediately perceptible to a layperson.

Generative AI tools can provide substantial efficiency and

reduced costs when used for appropriate tasks and with good inputs.

For example, tools for assessing examination reports and preparing

first drafts to respond to objections in those reports are

increasingly well developed and useful. Continuing investments will

undoubtedly produce IP prosecution tools that will be a welcome

addition to the toolbox for IP attorneys, freeing up time for

strategy and analytical tasks that cannot (at least not yet) be

accomplished by AI tools.

Originally Published by Lexpert Business of Law

The content of this article is intended to provide a general

guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought

about your specific circumstances.