China-made electric vehicles: Geopolitics at the wheel

This is the 157th in the China Chronicles series.

China’s dominance over low-carbon energy technology value chains is unambiguous. China holds at least 60 percent of the world’s manufacturing capacity for most mass-manufactured low-carbon technologies such as solar PVs, wind systems, and batteries and 40 percent of electrolyser manufacturing (hydrogen production). China leads the world in renewable energy (RE) consumption and in solar and wind power generation with 30-35 percent share of the global total in each. Rather than recognising China’s contribution to the growth of RE’s global share, vital for addressing climate change, China’s investments and capacities in the low-carbon energy sector in general and the electric vehicle (EV) sector, in particular, are being portrayed as a security threat mostly by the United States (US) and its Western allies but also by some developing countries. This position is driven more by the threat to legacy automobile industries and domestic jobs and less by national security concerns.

China leads the world in renewable energy (RE) consumption and in solar and wind power generation with 30-35 percent share of the global total in each.

The electric vehicle value chain

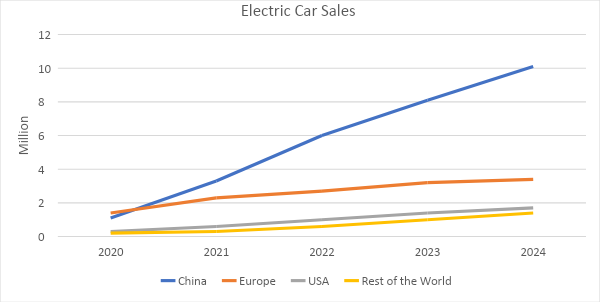

In 2023, China, the US, and Europe accounted for over 65 percent of car sales and 95 percent of EV sales globally—out of which China accounted for 60 percent of EV sales, Europe 25 percent, and the US 10 percent. China dominated battery production for EVs with over 83 percent of the global total and close to 60 percent of EV manufacture in 2023. Europe and the US together accounted for approximately 13 percent of global capacity. Although the mining of critical minerals required for manufacture of EV batteries is geographically dispersed to some degree, China’s control over the rest of the EV value chain is intimidating. China dominates the processing of all critical minerals with over 65 percent share for lithium, over 35 percent for nickel, over 75 percent for cobalt, over 90 percent for high purity manganese and almost 100 percent for graphite. 70 percent of battery production capacity planned for 2030 is in China. China also accounted for about half of the current global capacity for battery recycling. Although China’s dominant position is expected to be retained due to announced additional capacity of 3 terawatt per year (TWh/year) by 2025 and 4.7 TWh/year by 2030 (75 percent of total additional capacity) but China’s share in the total is expected to decline to some extent.

China is the world’s largest EV battery exporter and the battery production value chain of China is more integrated than in the US or Europe, given China’s domination of most segments of the EV supply chain. China represents nearly 90 percent of global installed cathode (negative terminal of the battery) active material manufacturing capacity and over 97 percent of anode (positive terminal of the battery) active material manufacturing capacity. China is home to almost 100 percent of the Lithium Ferrous Phosphate (LFP ) production capacity and more than 75 percent of the installed lithium nickel manganese cobalt oxide (NMC) and other nickel-based battery production capacity. Domestic and regional production can meet demand for batteries from the EV sector in China, Europe and the US. However, Europe and the US import more than 20 percent and more than 30 percent of EV battery demand, respectively.

China is the world’s largest EV battery exporter and the battery production value chain of China is more integrated than in the US or Europe, given China’s domination of most segments of the EV supply chain.

In terms of cost competitiveness, China remains unbeatable. Producing a battery cell in the US is at least 20 percent more expensive than in China even when assuming that material costs are identical. In reality, material costs for Chinese manufacturers may be lower as China has near total control over the supply chain. In addition, most Chinese batteries are LFP, which is more than 20 percent cheaper to produce than NMC.

In 2023, China used less than 40 percent of its maximum cell (battery excluding cathode and anode) output, and installed capacity for cathode and anode production was almost 4 and 9 times greater than global EV cell demand in 2023. As in the case of the steel and solar industries in the past, China’s industrial policy-driven strategy for developing the EV value chain has resulted in significant excess capacity. Capacity utilisation stood below 70 percent among the top EV manufacturers in 2023. This has significantly decreased the profitability of Chinese EV manufacturers, many of whom are now looking at markets outside China. The US and the EU, which are among the top three markets for cars, is their obvious export destination.

Foreign policy meets industrial policy

In May 2024, the media reported that US President Joe Biden is preparing to increase the tariff on Chinese EVs from 25 percent to 100 percent. Earlier in March, the US declared Chinese EVs a risk to its national security. During her visit to China in April, the US Treasury Secretary, Janet Yellen highlighted the issue of “overcapacity,” and criticised China’s excess production in green sectors as a threat to the US EV and solar industries. During Xi Jinping’s visit to Europe in May, the President of the European Commission observed that Europe could not absorb the massive over-production of Chinese industrial goods flooding its market.

China had a spectrum of policies to boost domestic EV and battery production and the EU’s Green New Deal supported domestic production of EVs and imposed tariffs on imports.

The clean vehicle (or EV) tax credit in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) of the US, an instrument that characterises the US’ return to industrial policy, has created large financial incentives for friend-shoring of EV supply chains or locating supply chains in allied countries primarily to reduce dependence on China. Any critical minerals or battery components from China and other unfriendly countries will disqualify a vehicle from eligibility, starting in 2024 for battery content and in 2025, for critical minerals. Among the criteria set by the US for support under IRA is that it must have national security implications. China and the EU introduced major industrial policies before the IRA or the CHIPS Act. China had a spectrum of policies to boost domestic EV and battery production and the EU’s Green New Deal supported domestic production of EVs and imposed tariffs on imports. The EU has been investigating the imports of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) from China as part of its Green New Deal.

In the context of EVs, industrial policies put in place supposedly to protect national security will impose additional costs on decarbonising mobility. The energy sector is the source of around three-quarters of greenhouse gas emissions today and decarbonising the energy sector is seen to be critical in limiting the negative consequences of climate change. Electrification of surface mobility can reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and local air pollution, particularly in urban areas. According to calculations by the International Energy Agency (IEA), if all Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles and hybrid EV sales of sports utility vehicles (SUVs) around the world were pure battery-driven EVs (BEVs) in 2023, about 770 million tonnes CO2 could have been avoided globally over the cars’ lifetimes. This is a little over a fourth of India’s CO2 emissions in 2022. However, the three regions that account for nearly three-quarters of car sales are erecting barriers to the trade of affordable EVs in the name of national security. This could increase overcapacity, heighten geopolitical tension, and slow down efforts to decarbonise mobility.

Oil majors eventually won as cheaper imported oil drove industrial production and economic growth in the US.

As distorted as the idea of national security is, it offers an excellent allegory for industrial actors to claim protection. In the 1960s and 70s, small high-cost oil producers in the US argued that imported oil threatened national security while international oil majors argued that cheap imported oil contributed to national security. Oil majors eventually won as cheaper imported oil drove industrial production and economic growth in the US. In the age where technology has replaced energy as a strategic commodity, the same arguments can be made about EVs: Domestic EV manufacturing sustains domestic jobs and thus protects national security but the import of affordable EVs accelerates decarbonisation of road transport and limits harm caused by climate change, preserving national security.

Lydia Powell is a Distinguished Fellow at the Observer Research Foundation

The views expressed above belong to the author(s). ORF research and analyses now available on Telegram! Click here to access our curated content — blogs, longforms and interviews.