Designers of collaboration mandates for sustainable natural resource management must address public agencies’ concerns about losing autonomy and influence

With climate change now influencing entire regions, there is a greater need for organizational collaboration to manage natural resources sustainably. Using California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which mandates collaboration between groundwater sustainability agencies, as a case study, Brian An and Shui-Yan Tang examine what drives integrative collaborations between agencies. They find that agencies are more likely to joint integrative collaborations if their mission addresses a broader focus, their core stakeholder groups have less concentrated interests in the policy issue, and their organizational culture is less rigid and risk averse.

With climate change now influencing entire regions, there is a greater need for organizational collaboration to manage natural resources sustainably. Using California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, which mandates collaboration between groundwater sustainability agencies, as a case study, Brian An and Shui-Yan Tang examine what drives integrative collaborations between agencies. They find that agencies are more likely to joint integrative collaborations if their mission addresses a broader focus, their core stakeholder groups have less concentrated interests in the policy issue, and their organizational culture is less rigid and risk averse.

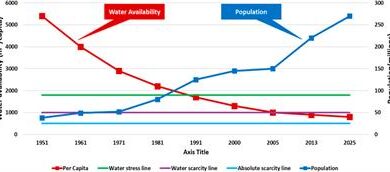

With climate change increasingly transforming our environment, governments and communities worldwide face critical challenges in managing natural resources sustainably. Resources like air, fisheries, and groundwater— called common-pool resources – often pose intractable management problems as their scale and scope may not align with existing political or administrative boundaries. Without policy mechanisms to bring together the independent efforts of different state and local governments and other stakeholder groups, sustainability remains a mere buzzword. Policymakers can advance their sustainability goals by using inter-agency collaboration mandates to push stakeholders to work together. But they first must understand why certain public agencies may be overly attached to their bureaucratic “turf”, and what prevents them and others from developing integrated collaborative frameworks that match the scope of the underlying collective action problems. Our work unpacks these agency-specific characteristics to inform the design of collaboration mandates and offers valuable lessons for policymakers and public managers interested in their use.

Public agencies’ concerns for turf loss when collaboration is wider in scope

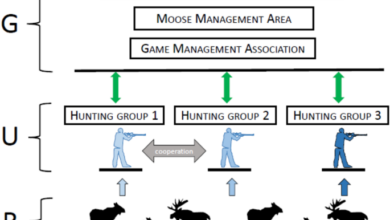

Most research which studies the collaborative governance of natural resources looks at either system or agency-level drivers and focuses on the specific forms of collaboration among those already involved or linked to an agency (the horizontal dimension of collaboration). Relatively little research has examined questions which cover the number of those who are involved, and the scope of collaboration (the vertical dimension of collaboration).

When government agencies explore options for joining an integrated public governance process to meet a collaboration mandate which has been externally imposed, they are often motivated to hedge against the risks of facing adverse outcomes which can result from severe conflicts with other organizations that are taking part. Specifically, externally imposed deadlines and considerable uncertainties can make the usual drivers for horizontal collaboration under voluntary bargaining—collaboration capacity, prior collaboration, problem severity, external facilitation, among others—less relevant for an agency’s choice on how integrated and encompassing their collaboration arrangement should be. Instead, our research shows that factors related to an agency’s autonomy and turf loss drive their choice on the vertical dimension of collaboration.

California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act

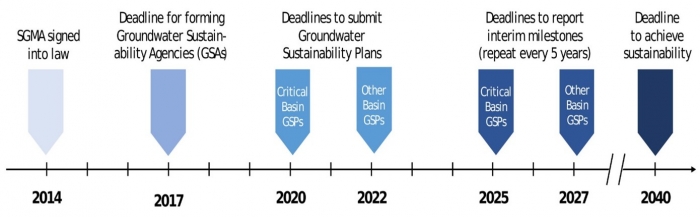

Our study setting uses the inter-agency collaboration requirement described in California’s ongoing Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA), launched in 2014. SGMA required the creation of new regulatory agencies, called groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs) by 2017, encouraging them to collaborate with one another. It then mandates these new GSA agencies to develop a single groundwater sustainability plan or coordinated ones for the entire basin to be implemented over the next 20 years.

SGMA’s flexible and tiered collaboration requirements provide a valuable window to examine how collaborative governance unfolds under the shadow of a state mandate. The initial formal collaboration framework adopted by agencies may significantly affect each agency’s ability to protect their respective interests and the prospect for success. Possible collaboration frameworks under the SGMA include forming a stand-alone GSA, joining a few other agencies to form a multi-agency GSA, or joining a single basin-wide, multi-agency GSA at the start.

Figure 1 – SGMA Mandate Timeline

Notes: Various collaboration milestones for sustainability to be achieved by SGMA.

A critical choice for an agency is, therefore, whether to join others to establish a regionally integrated GSA that covers the entire basin. With regional integration, agencies can work early on within a framework that matches the basin’s scale, reducing potentials for distributive conflicts, incoordination, and disputes down the road. The tradeoff, however, is that by joining regional integration upfront, an agency may lose its discretionary autonomy and be constrained by uncertain future collective decisions within the framework.

Our analysis uses data derived from archival records and a statewide survey of local groundwater managers whose agencies have chosen divergent collaborative arrangements in response to the mandate set out in the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act.

“California Aqueduct from Interstate 5, S” (CC BY-SA 2.0) by Ken Lund

Three major drivers for a regionally integrated collaboration arrangement

After accounting for the usual drivers of inter-agency collaboration set out in the literature, our analysis shows that, when the agency’s core mission and their key constituencies’ interests are at stake, agency officials focus on their own organization’s priorities: protecting organizational autonomy and bureaucratic turf by not participating in a regionally integrated arrangement. Such risk calculus overwhelms prior trust, collaborative experience, and leadership efforts. In other words, many well-known factors that contribute to voluntary collaboration become less relevant when agencies must consider participating in a more regionally integrated collaboration arrangement under the state mandate.

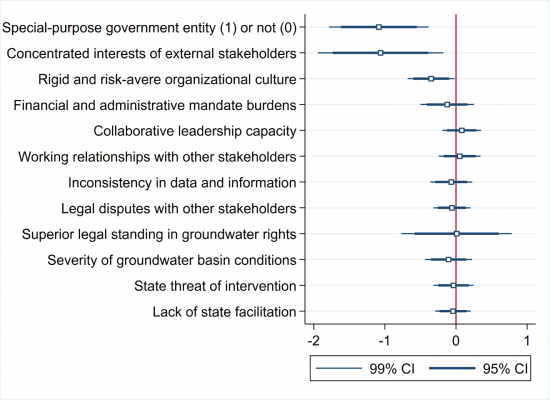

We used several analytical methods to examine which agencies are more likely to commit to regionally integrated collaboration that matches the scale of a groundwater basin. As Figure 2 shows, we find that agencies are more likely to collaborate in this way if their mission addresses a broader issue focus (i.e., general-purpose local government entities rather than special-purpose governing entities), their core stakeholder groups have less concentrated interests in the policy issue, and their organizational culture is less rigid and risk averse.

In contrast, other well-known drivers of horizontal collaboration do not matter in explaining agencies’ likelihood of participation in regionally integrated public governance.

Figure 2 – Drivers for Agency Choice on Regionally Integrated Public Governance

Notes: n= 107. This figure summarizes the results of probit regression in which the dependent variable is whether an agency participated in a regionally integrated GSA or not. The first independent variable in the list is (single) issue specificity, measuring if an agency is a special-purpose government entity (coded 1) or a general-purpose government entity (coded 0). The next variable measures the extent to which an entity has major external stakeholders with concentrated interests in the policy issue. It is operationalized by a survey-based Herfindahl-Hirschman Index with four groundwater consumption sectors: (1) agricultural use, (2) domestic and municipal use, (3) industrial use, and (4) other use. Full results and details can be found at https://doi.org/10.1093/jopart/muac014.

Inter-agency collaboration mandates must address agencies’ concerns for autonomy and turf loss

By unpacking the agency-specific sources of turf and reputation protection, our research contributes to an understanding of risk management in government mandate use. Our findings mean that state authorities should reconsider imposing overly rigid collaborative mandates on local agencies. If agencies face the prospect of being forced to deviate from their core issue responsibilities and constituencies, they will be inherently cautious about working with one another toward an integrated public governance framework. Principled engagement and shared motivation can develop more effectively if the mandate includes procedural arrangements that can protect agencies from potential risks of autonomy and turf loss.

Agencies serving external stakeholders with highly concentrated interests must be convinced that the long-term benefits of collaboration outweigh the potential losses. Otherwise, they will only protect their existing rights without the benefits of working in an integrated collaborative framework. Also, general-purpose government entities whose mission addresses a broader issue focus tend to be more willing to engage in a more regionally integrated form of collaboration than special-purpose entities when mandated to collaborate. As well as considering, agency-specific characteristics and incentives, when designing mandates, policymakers may draw on these entities’ resources and leadership to spearhead collaborative efforts.

Please read our comments policy before commenting

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3A9CA3M

About the authors

Brian Y. An – Georgia Institute of Technology

Brian Y. An – Georgia Institute of Technology

Brian Y. An, PhD, is an assistant professor in the School of Public Policy at the Georgia Institute of Technology. His research examines how governance design and institutional choice affect policy and management processes and outcomes at all levels, from local and regional organizations to national governments across the globe. At Georgia Tech, he leads the Urban Research Group. He also co-leads the Pandemic Governance Research Group—a multi-institution and international team.

Shui-Yan Tang – University of Southern California

Shui-Yan Tang – University of Southern California

Shui-Yan Tang, PhD, is the Frances R. and John J. Duggan Professor in Public Administration and Chair of the Department of Governance and Management in the Sol Price School of Public Policy at the University of Southern California. His research focuses on institutional analysis and design, collaborative governance, common-pool resources, and environmental politics and policy.