Do You (Really) Need A Chief Artificial Intelligence Officer?

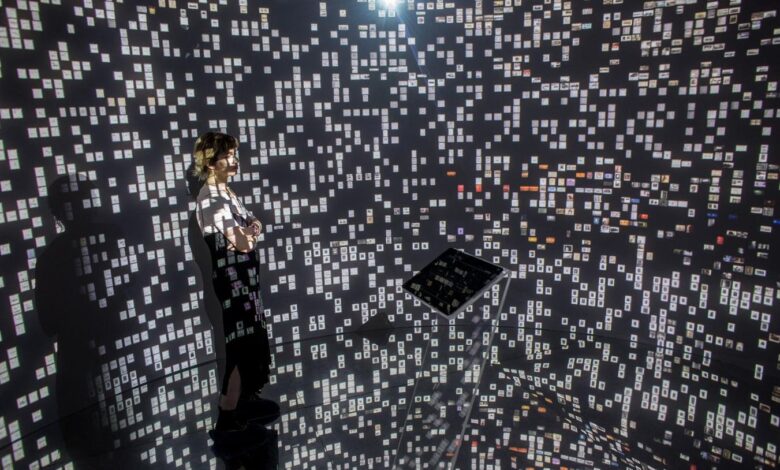

ISTANBUL, TURKEY – MAY 06: A woman views historical documents and photographs displayed in a high … [+]

AI is changing business profoundly and quickly. It is enabling new business models, making existing business models radically more efficient, and creating the potential for products conceived in entirely new ways. It is also making individual contributors more productive at day-to-day tasks, from writing code to writing memos. How should business leaders manage the breadth and depth and speed of this disruption?

Many people are advocating for a new role, that of a Chief AI Officer. President Joe Biden has issued an Executive Order on the Safe, Secure, and Trustworthy Development and Use of Artificial Intelligence, which requires that each agency designate such a leader. The Department of Justice is the first to do so, naming a Princeton computer scientist its Chief AI Officer. Mark Minevich, a Forbes Contributor, writes about “The Rise Of The Chief AI Officer: Powering AI’s Corporate Revolution.” The New York Times headlined, “Hottest Job in Corporate America? The Executive in Charge of A.I.”

Clearly something is happening. A common element in these articles is the description of a job with an extraordinary breadth. The person must be strategic, operational, deeply technical, transformational, and capable of integrating ethics with AI initiatives. Is this even possible? If it were, is it really the path to the integration of AI into the business?

In many ways, the call for a Chief AI Officer is akin to previous organizational responses to major new technological capabilities, like the Head of Re-engineering, the Chief eBusiness Officer, the Chief Data Officer and the Chief Innovation Officer. In each case, the goal was to put an executive in charge who could work across functions, break down silos, and accelerate change.

But Jane Edison Stevenson, Vice Chair of Board and CEO Services at Korn Ferry, believes that something more fundamental is happening this time. She has lived through the earlier waves with a bird’s eye view as an executive recruiter, and she was a leader in recruiting some of the very early Chief Innovation Officers. Stevenson believes that AI is a disruptive technology that all executives need to embrace – and she has not come across any who are in denial about this wave of change. The question remains: how should businesses adapt?.

The larger frame within which to place this challenge is what Stevenson calls enterprise leadership: the “ability to both perform and transform simultaneously and to think horizontally, not just vertically.” “The ability to perform consistently is table stakes,” she told me in an interview. “The need (is) to transform real-time, every day, at the same time that you perform”. AI is an important part of the current complexity this new breed of executives must manage. Although a Chief AI Officer may provide coordination and awareness, the need is deeper.

So what should executives do to respond to the AI revolution? It depends on your function. The Chief Strategy Officer needs to become deeply aware of the potential of AI to challenge the business model and strategy of the firm. This includes the potential for AI to create a new set of competitors who compete by embedding AI into every aspect of their operations. In Competing in the Age of AI, Marco Iansiti and Karim Lakhani give examples of companies that have created an ‘AI factory’ at the heart of their operations. Companies as different as Moderna and Ant Financial generate economies of scope and economies of scale at the same time. They do so by using AI to improve and speed up entire processes. People become monitors of the process and are out of the flow of execution. The Chief Strategy Officer needs to understand these new operating models and lead the organization on paths that can survive the existential threats and realize the extraordinary potential of AI.

The Chief Innovation Officer needs to look at AI through a different lens. He or she needs to foster experimentation with the ways AI is being used to dramatically increase both innovation speed and breadth. Experiments with specialized tools like Ethan Mollick’s Innovator, available through ChatGPT, indicate the potential. Mollick has shown that his students at the University of Pennsylvania move through the front end of innovation faster and more creatively when using such tools. He mandates their use in his classes.

AlgoVerde, a Silicon Valley startup, has integrated a generative AI innovation platform across the design lifecycle. Vladimir Jacimovic, CEO of AlgoVerde, says that the use of virtual twins of both customers and technical experts “can speed the path of innovation from business challenge to concept by a factor of ten“(emphasis added). To understand the role that generative AI could play in their functions, Chief Innovation Officers need to do experiments and encourage their staffs to do the same.

Chief Technology Officers and R&D leaders face a different opportunity. They can use AI to simulate products before they are even prototyped, including their integration with customer systems. They can speed up R&D processes, sometimes dramatically. Daniil Boiko, Robert MacKnight and Gabe Gomes, all of Carnegie Mellon University, used generative AI to create an AI system “for autonomous design, planning, and execution of scientific experiments,” for example, greatly increasing the pace of their research. Generative AI can also be used to increase the design space for products, as AutoDesk has demonstrated with 3D printing designs created using generative techniques. Finally, CTOs can use generative AI to create smart and accessible products – products that are easier to use and to personalize than was previously possible.

Chief Operating Officers must lead the use of AI to improve operations. This often starts with the automation of point solutions. Many companies see call centers as a ripe opportunity, though simple displacement of jobs may not be the best approach. There is room for an entirely new wave of re-engineering, one driven from the shop floor up.

Even Chief HR Officers have a unique role in the integration of AI into operations. They need to understand the emerging tools and how individuals can be empowered to use them in their work. There are already concerns that such tools might leak confidential information or create security threats. At the same time, a large body of studies is demonstrating that the use of large language models can increase productivity across a range of knowledge work in surprising ways (see “Navigating the Jagged Technological Frontier: Field Experimental Evidence of the Effects of AI on Knowledge Worker Productivity and Quality). Today, many companies limit the use of generative AI because of security and IP concerns. CHROs can break down roadblocks and encourage experimentation and sharing of results. CHROs may also take a lead in highlighting ethical issues.

The point is that the role of leading in the Age of AI is not one that can be managed by an individual, no matter how skilled. Each member of the C-Suite needs to find ways that will move his or her role to the next level. This requires that they each become educated on the potential – and spend time experimenting with tools themselves. Without some hands-on experience, the potential will seem abstract.

The easiest thing in the world a CEO can do to respond to the threat of this uncertain and poorly understood technology is to appoint a Chief AI Officer. The problem is that it is unlikely to be the silver bullet that it promises to be. At worse, it might cause others to defer their own learning journey and delay real adoption.