Experiential Robotics Platform brings STEM into more classrooms

From left: Spark Academy high school students Rowan Frawley, Aiden Fournier, Connor Frawley and Quinton Pray study robotics at Manchester Community College. (Photo by Jodie Andruskevich)

A loud hum of fans can be heard at a facility at Manchester Community College (MCC) as rows of 3D printers produce tools that will go out to students in public and private schools across New England and beyond. Those tools are, in part, designed by local Granite State high schoolers.

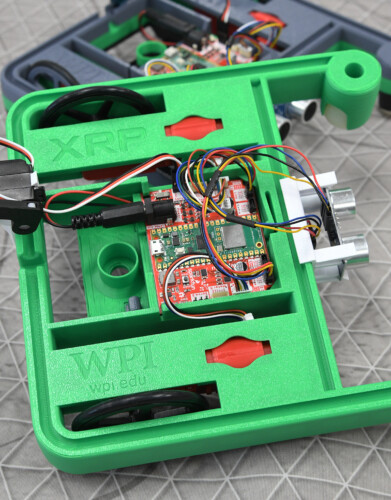

The printers are creating bodies of robotics kits that make up the Experiential Robotics Platform (XRP), an open-source robotics education initiative meant to introduce grade-school and college students to robotics, engineering and software development. To do this, XRP uses small introductory robots made up of a 3D-printed plastic chassis, and a custom-developed circuit board — all of which can be had for just under $115, or a discount rate of $65 for schools or robotics teams under Manchester-based FIRST Robotics.

The circuit board is comprised of various electromechanical parts and a Raspberry Pi microcontroller — a tiny computer onboard the kits allowing students to code and program functions. Accompanying the robot is a freely available curriculum developed by Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) through the university’s OpenSTEM initiative designed and intended to teach not only students but also their educators and even hobbyists about how to assemble, control and manipulate the XRP robot.

XRP’s lead student testers are found in that same facility at MCC, enrolled in the college’s Spark Academy of Advanced Technologies, a comprehensive public charter high school that launched in 2019, serving teens in grades 9-12.

“We pretty much already went through the learning phase on the 3D printers, but occasionally need to learn something new, like some random issue with them,” said Quinton Pray, of Amherst, a student at Spark. “What we’re currently doing is dealing with assembly and overviewing what other people are doing, trying to fix their mistakes if they do something that they probably shouldn’t.”

Unlike other public high schools that broadly teach general subjects and may have robotics instruction as an elective course or extracurricular offering, Spark Academy instead puts that front and center in addition to having humanities, math and health classes. XRP is central to that structure, and students like Pray and his peers are among the first to demonstrate its curriculum in action.

The XRP initiative is currently rolling out to schools via SparkFun Electronics, a Colorado-based electronics retailer whose engineers created the custom circuit board for XRP kits, according to Dan Larochelle, Spark Academy’s founder, and the department chair of MCC’s advanced manufacturing and robotics program.

The circuit board — which can be programmed using the coding language Python — includes components like two servo motors, a gyroscope, an ultrasonic rangefinder and a line follower, enabling the robot to seek and follow drawn lines when directed by software.

Larochelle said XRP formally launched two years ago, but its origins go back much further before Spark Academy was conceived.

“The whole concept of this is to make a generic robot that kids can play with, really to make a programming in Python class come alive,” Larochelle said. “The goal was to make a robot that was about $50 that we can send to Africa.”

About half a decade ago, Larochelle became involved in a project helmed by Worcester Polytechnic Institute professor Bradley Miller, who taught robotics engineering and was former associate director of the school’s Robotics Resource Center. Larochelle and Miller had met in 2006 through a separate robotics project unrelated to XRP, according to Miller.

Today a senior fellow of WPI, Miller said the project stemmed from then-Dean of Engineering Winston Oluwole Soboyejo’s desire to foster STEM education among schoolchildren in African nations at an affordable cost. Soboyejo, born in Palo Alto, California, but raised in Nigeria, felt more needed to be done to make STEM instruction more marketable to youth there.

At first, Larochelle said, the robots were a great teaching tool, but after a year the motors failed and led WPI and other partner organizations to end the project. From that failure, however, emerged a new strategy and an extension of educational opportunity: have students build the robots themselves, which would make them more modular and reduce retail price. At a lower cost, learning institutions may order more robots for individual students.

“Now the concept for this is to send (students) a bag of electronics that cost about $15, and send them the files to do whatever they want,” Larochelle said.

Thus, XRP was born, publicly launching in October 2022, according to David Rogers, chief development officer for DEKA. The Dean Kamen-led tech company and Kamen’s nonprofit FIRST Robotics are both core partners of XRP.

“I’ve been working on this project for about three or four years now,” Rogers said, with his and DEKA’s interest in the platform stemming from previous research work with the National Science Foundation (NSF) to implement robotics instruction into every school in the US.

“At the same time as we were doing this research, Brad Miller — who was a good friend — was trying to evangelize the concept of small-scale robotics,” Rogers recalled. “It really took off during COVID, when people couldn’t meet together face-to-face. They needed solutions that students could work on in their own homes.”

Rogers said he and other partners initially expressed reservations, mostly about any such small robots being developed for a closed software ecosystem, so the decision was made to seek what he called an “open source and community-driven (product), and not so much an EdTech product.”

“We took kind of an unconventional approach of getting together a bunch of partners to do an open-source, consortium-driven effort,” Rogers said, leading to outreach to partners like Manchester Community College.

That’s also where partner DigiKey, a Minnesota-based electronics distributor, comes in. Rogers credits DigiKey’s David Sandys, senior director of technical marketing, with having the right industry connections to construct the XRP consortium and promote the platform outside of New England.

“We do business in 22 currencies across 181 countries that we ship to,” Sandys said. “But it’s hard for us to get skill in a STEM environment if we were to hit one school at a time. So, we’ve engaged with companies and organizations like FIRST Robotics for years now, because it’s a great way for us to get messaging and help to really ensure that engineering is a living and breathing dynamic field within North America.”

Sandys said he and others at DigiKey first became aware of XRP in late 2022 and were impressed by DEKA and WPI’s collaborative work to develop the platform. However, the two entities had struggled to find partners to provide the electromechanical components needed to produce XRP kits — whose design was not fully completed — at a mass scale for national distribution.

“That’s where DigiKey excels; we are a company that has somewhere in the neighborhood of 15.3 million electronic parts on our website,” Sandys said. “When we were looking at some of the challenges we spoke to David (Rogers) about, it became abundantly clear that we could bring in some of our suppliers to help alleviate these pain points, so we brought in SparkFun.”

He’s referring to SparkFun Electronics, which besides distribution, suggested that DEKA and WPI use the Raspberry Pi RP2040 as XRP’s microcontroller. It was thanks to their insight that the robotics platform could finally begin production of its kits.

Spark Academy student, Rowan Frawley watches as a 3D printer makes the chassis for the Experiential Robotics Platform at Manchester Community College. (Photo by Jodie Andruskevich)

“Last year, six of the MCC and Spark (Academy) students built 600 of these and put them in the FIRST Global Challenges,” MCC’s Dan Larochelle said. “Today, we do everything from the quality control, the inspection and the assembly. We build all these little kits, package them in bigger boxes of 10, and send them out to schools across New Hampshire.”

Within the Granite State, XRP robots are being shipped to schools thanks in part to the New Hampshire Robotics Education Fund, launched by Gov. Chris Sununu and Dean Kamen in 2017 to commit to creating a statewide robotics educational program. Sununu visited MCC and Spark Academy in February to observe the XRP assembly process, posting photos of the occasion to social media site X, formerly Twitter.

“What we’re doing in New Hampshire now is professional development training for teachers,” WPI’s Bradley Miller said. “They come in (to Spark Academy) and get trained on XRP, and they walk out with 20 robots for their classroom. All together it comes out to about 5,500 robots — that’s what the state has paid for.”

Miller said that equates to roughly $450,000 from the state government for XRP robotics kits. Meanwhile, back at Spark Academy, Larochelle said students will remain core to the local rollout and development of XRP while seeing the personal benefits of their involvement.

“Last year, six students got a stipend for building these that was funded by DEKA and one of the grants that we had,” he said. “This year, we created an entire ELO (extended learning opportunity) program, so the students will actually get high school credit for doing some of this.”

And even after the end of the school year in summer, Larochelle said the 3D printers will still be humming.

“We’re in the process of creating another grant or opportunity for if kids want to come in the summer where we’ll pay them to keep the printers running and the manufacturing going forward,” he said.