Frederick Celani, Who Made a Career as a Con Man, Dies at 75

Frederick Celani was more than a decade into a rollicking, relentless career as a con man when he bamboozled city officials and employees in Springfield, Ill., into believing that he would make the city the hub of an overnight package delivery service.

It was 1983. Unemployment was high in Springfield, which needed the economic boost that Mr. Celani was promising. In a whirlwind few months, he hired 100 workers, including pilots; leased cars; and rented office space and an airplane hangar.

On March 1, about 1,000 people gathered at the hangar to celebrate Kayport Package Express’s first day in business. Champagne was served. A high school band played.

But it was over in four days. All the employees were laid off.

And Mr. Celani skipped town for Los Angeles, according to an account in a three-part series about him in The Standard Journal-Register of Springfield, which began in 2007.

The Kayport scheme — part of a broader fraud that involved bilking hundreds of investors around the country out of nearly $4 million for phony tax shelters and company stock — led to indictments against Mr. Celani (pronounced CHELL-ah-nee) and his partner, Aaron Binder, for racketeering, conspiracy, and mail and wire fraud charges.

Mr. Celani defended himself at his trial, with assistance from a lawyer, Jon Noll.

“To him, the trial was a tremendous amount of fun,” Mr. Noll told The Journal-Register. “It was a new adventure for him.”

Mr. Celani was sentenced to 15 years in prison — he served six — and Mr. Binder to 10 years.

The cons would continue after Mr. Celani was released.

“The thing that I thought was odd,” Bruce Rushton, who wrote the three-part series, said in a phone interview, “is that of all the people I talked to, nobody was mad at the guy.

“They saw the humor in it.”

Mr. Celani’s body was found on Feb. 7 in Queens, according to a listing on the National Missing and Unidentified Persons System that includes a postmortem photograph of his face. The New York City medical examiner’s office said the cause of death was cardiovascular disease. He was 75.

Frederick George Celani was born on Aug. 26, 1948, in Buffalo, to Joseph and Grace Celani. His father was a bus driver. The federal judge sentencing Mr. Celani in a real estate scheme in 2013 cited a presentencing report saying that he had been beaten by his father and brother when he was young.

Mr. Celani and his first wife, Anita Celani — they married in 1971 — eventually divorced. In 1991, she was convicted of second-degree murder for hiring a hit man to kill a later husband, Robert DiGiulio. Mr. Celani later married Mary Rudolph.

Information about his survivors was not immediately available.

By his own account, Mr. Celani never held a legitimate paying job. And while he took courses at Canisius College (now University) in Buffalo from 1976 to 1977, he did not matriculate.

His history of hoaxes began in his hometown. In 1974, he was sentenced to a year in prison for being the mastermind of a bogus plan to build a $100 million waterfront development — all while being held in the Attica Correctional Facility for another case that involved taking $2,000 from a couple for a house that he didn’t intend to build.

At his sentencing for the waterfront fraud, the judge, Robert F. Kiener of West Seneca, N.Y., said: “Robert Redford and Paul Newman received recognition for their roles as con men in ‘The Sting.’ But you, Mr. Celani, for your efforts, have been stung.”

Stung, perhaps, but unbowed. He enjoyed what he was doing too much to stop.

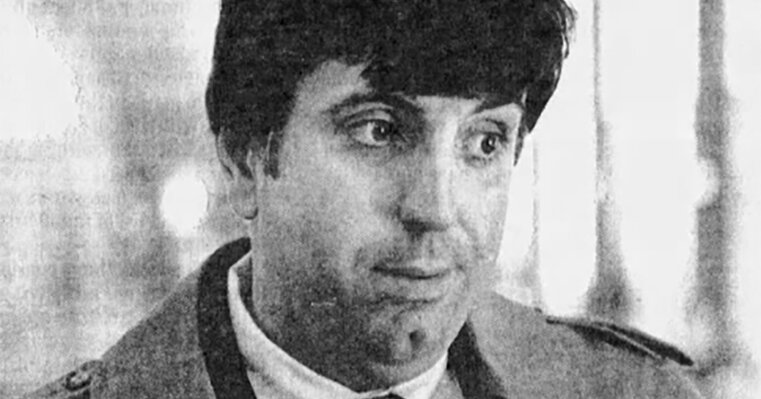

“He was smart, shrewd, a great talker with a baby face, friendly but never slick,” Mr. Rushton wrote in the Journal-Register series.

“You expect a con artist to be suave. He wasn’t,” Thomas Glascott, a retired Buffalo police lieutenant and district attorney’s investigator, was quoted as saying.

Soon after being released from prison in 1991 after serving time for the Kayport scheme, Mr. Celani turned up in North Hollywood, Calif., as Fred Sebastian, the founder of a civil rights law firm that he called the Center for Constitutional Law and Justice. He was not a lawyer, but he hired five attorneys to represent federal inmates, some of whom paid the center thousands of dollars, hoping to overturn their convictions or get them early release.

It was also a scam.

“He could sell ice to Alaskans and shampoo to the bald,” Alaleh Kamran, one of the center’s lawyers, told The San Francisco Examiner in 1993. “If you didn’t know he wasn’t an attorney, and I didn’t, he could really fool you.”

The center collapsed after Mr. Celani was arrested in 1992 for promising an inmate’s wife that he could get her husband released from prison if she gave him $50,000 to bribe the prosecutor in Little Rock, Ark. She told the F.B.I. about the offer and recorded a conversation with Mr. Celani about the bribe. He was convicted of eight counts of fraud and sentenced to seven years in prison.

At his sentencing, Mr. Celani claimed that his troubled life had its roots in his alcoholic parents’ kicking him out of their house, turning him into a “kid on the street.”

The judge called him a “human tragedy.”

In 2000, he was free again. Under the name the Rev. Bob Hunt, he reprised his earlier legal scam. Posing as a lawyer and also as a minister, he offered legal services to federal inmates. An estimated 150 inmates were defrauded of nearly $200,000, according to court documents.

“Needless to say,” Mr. Celani said at the 2013 hearing, “there’s a whole bunch of unhappy inmates coast to coast who would like to see me as soon as possible.”

He also started a congregation in East Peoria, Ill., where he once delivered a sermon called “Honesty.”

In 2004, he moved on to a real estate scheme on Long Island. Over the course of a year, he operated as a lawyer named Sidney Levine who, with at least two partners, cheated investors out of $8 million that the partners said they would use to buy, build and refurbish assisted living facilities, guaranteeing a 25 percent annual return. They paid about half the money to themselves and only $850,000 in interest to investors.

When F.B.I. agents confronted Mr. Celani at his office in 2005, he told them that he was a diabetic and needed his insulin. He left and did not return. Four years later, he was arrested near his office in Oakdale, N.Y., on Long Island — he had been on the F.B.I. most-wanted list as Sidney Levine — and revealed in a court appearance that he was Frederick Celani.

He spent the next nine years in prison and pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit wire fraud and money laundering. While incarcerated, he had three strokes and lost vision in one eye.

At his sentencing hearing in 2013, he said: “The first 64 years of my life is nothing to be proud of. What I did, I did. And I apologize to the court and to those I have harmed.”

Two months after his release in 2018, he described himself as a “homeless man” on a Facebook post that asked for donations to a GoFundMe campaign.