Generative AI Is Broken. We Need to Break It More

Artificial intelligence, specifically generative and large language model (LLM) AI, has come a long way and is currently one of the biggest trends to watch in technology, media, law, and even medicine. It’s also a flawed, hastily implemented, and dangerous trend.

I’m not a Luddite. I’ve been an ardent technophile all my life, and I think AI has a lot of potential. But we’re moving too quickly in some areas, in part because many industries see the potential to save money on labor. AI has a lot of problems, and most of them can be fixed. We just have to break AI even more before it becomes truly useful.

The Problems: Standards, Quality, and the Human Factor

(Credit: Google)

I’m not going to talk about creative uses for AI; we don’t need to argue about the validity of AI art. Of bigger concern is its tendency to screw up when conveying quantifiable information, or when parsing and condensing a combination of quantifiable and qualitative information.

Fill its pool of training data with raw manufacturer specs or a consistent database with testing data and it can spit them out reliably. Expand that pool to mix those specs with testing data, user reviews and complaints, fake reviews, and snarky and community-specific jargon and you get some very confused summaries.

In some cases, this can result in AI giving wrong or outright dangerous information. NYC’s AI chatbot told businesses to break the law. The National Eating Disorders Association (NEDA) shut down its chatbot because it was giving dangerous advice about eating disorders. Broader chatbots, including Google Gemini and GPT-4, are providing voters with wrong information about polling locations.

LLMs can’t reliably evaluate the credibility of its training material, especially when media outlets, manufacturers, marketers, and scammers tailor their content to push it to the front of those models just like they do with search engine optimization (SEO). For chatbots that get their information from the general internet and not specific, controlled sources, anyone who wants to make sure their take on a subject gets heard will be working to game the system in an algorithm arms race that never stops.

I use a bunch of things in my work. I mean, physically use them. (Credit: Will Greenwald)

There’s also the fact that AI can’t do legwork. We’re a consumer technology website that reviews thousands of products every year. That means we test them. We consider the user experience. We physically use them. LLMs can’t. They can scrape the results of our work, sure, but they cannot pick up a device, take notes, run benchmarks, explore potential flaws, and give an accurate evaluation of its performance and value for the money.

Without our work, the only numbers AI can get are manufacturer specs and claims, and those claims are often false. At best, generative AI gives a fairly accurate summary of the results of our work. At worst, it can credulously repeat wrong claims and miss serious design and safety issues. In both cases, it pulls readers away from the people who produce the useful information in the first place, and we need readers in order to keep doing what we do.

AI can’t be implemented responsibly in these ways. Not yet, and perhaps not ever without serious legal and cultural guardrails to constrain it. That’s why, if AI has any hope in being used in a way that improves our lives, makes them better and more convenient without massive pitfalls, it needs to be broken first.

Drain the Pool: Legal Solutions

Technical solutions won’t solve AI’s problems yet, but legal ones might. LLM training datasets are vast and grimy, and regulations are necessary to drain, filter, and chlorinate them. We need laws that give clear limitations and specifications for the information sources LLMs use. I don’t mean intellectual property. I mean accuracy. The internet has some great and useful information on every subject, but for every must-know trick there are a dozen wrong or completely unhinged pieces of advice. Until AI can consistently separate the wheat from the chaff (which is going to be a constant battle with the chaff finding new ways to make itself look like wheat), it needs to be cut off from the utter gunk of the unfiltered internet.

AI firms need to be compelled to only use well-maintained, credible databases related to the subjects their tools cover. This is especially important if those subjects have anything to do with medicine, chemistry, engineering, law, or any other field where a mistake can get you arrested, injured, or killed. The stakes are too high for the remotest possibility that a chatbot giving cleaning tips might pull a Peggy Hill and tell millions of people to mix ammonia and bleach.

How do we determine what databases are credible? Academic accreditation, third-party evaluation, and/or peer review, perhaps—there are lots of standards and methods of creating standards that could work. And if we can’t find enough credibility to keep the pool clean, well, I’ll discuss that in the next section.

We also need strong legal protections regarding intellectual property, copyright, and LLMs. AI is a wild legal frontier and there isn’t enough legislation or precedent to keep AI from actively stealing work. It’s not just about generative AI art using the work of artists for training and those artists not getting compensated. It’s about all AI using the work of anyone who generates content and not compensating them. Like I said, a chatbot that can spit out a summary of a review in a search result keeps the reader from clicking on that review, and clicks are how those review sites get paid. We need legal precedent that clearly delineates what LLMs can use and what constitutes copyright and IP infringement. We also need legislation that requires those LLMs to compensate those sources, just like any partnership where an outlet’s material is licensed for publication elsewhere.

I’m not holding my breath for laws to fix things, though.

Poison the Pool: Less-Than-Legal Solutions

If the law can’t be updated to reasonably put restraints on AI and the scopes of its training data pools, social and economic pressure is necessary. Which is a problem, because while AI is clearly not ready to be used reliably and responsibly, laypeople can easily look at the result a chatbot gives and think it’s good enough. If they don’t know enough about the topic they’re asking about in the first place, they can’t recognize an incorrect response.

Recommended by Our Editors

So AI needs to get so bad that its limitations are undeniable. It needs to be catastrophically humiliated, on a massive scale. It needs to get so many things so wrong that its flaws can’t simply be swept aside as something that can eventually be fixed, and considered good enough to use in the meantime.

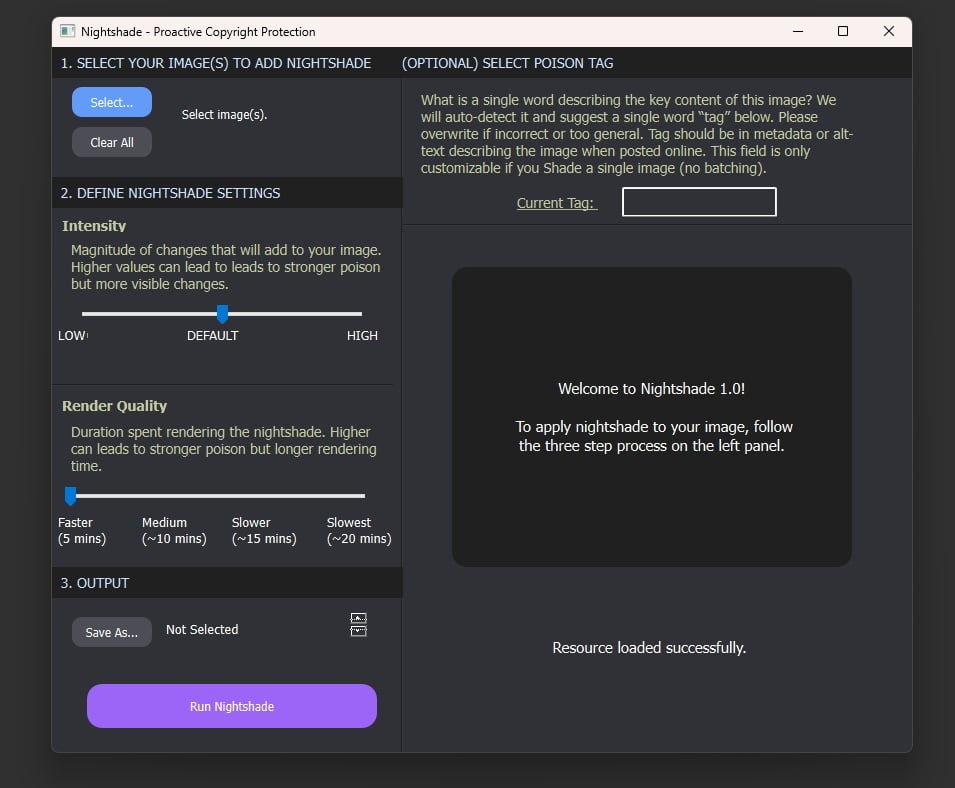

(Credit: Sand Lab/University of Chicago)

The answer to this is to outright poison the learning pools of LLMs. We’ve seen this tactic used legitimately in the form of Nightshade, a tool that injects information into art that gets scraped by generative AI engines to corrupt that training data. The same developer, Ben Zhao of the University of Chicago and his team, also created Glaze, another tool that helps obscure the style of artists to keep it from being scraped. It’s brilliant, and this type of tool should be used by every artist and photographer who puts their work online.

Text is trickier. Image files have plenty of options in how they’re compressed and encoded to hide data with corrupt learning pools without affecting what users see. Text is text, and while there could potentially be some way to poison that training data through scripting, metadata, or page layout, the text will still be there.

Okay, the usual preamble. I am in no way condoning or recommending any illegal action. This is purely a thought experiment about the potential effect an extralegal activity might have in response to current AI trends. Don’t break the law.

I don’t care what anyone says. Hackers is still a great movie. (Credit: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc.)

Anyway, what if a bunch of black hats came up with worms that actively poisoned the text training data scraped by LLMs? Something that would make them give complete nonsense answers en masse. Clearly wrong values, like saying a Honda Civic weighs 14 miles or that the capital of Portugal is a xylophone. Nothing dangerous like telling people to mix ammonia and bleach, but maybe the suggestion that they should mix ammonia and Nesquik. Something that makes the current implementation of LLMs not just unreliable and loaded with unfortunate implications, but outright embarrassing. If we can’t force AI to be used responsibly through legislation, we can stop it from being used irresponsibly through humiliation.

It’s just a thought. Honestly, there is no perfect solution here. Technological solutions aren’t sufficient. Legal solutions aren’t likely. Non-legal-but-technological solutions aren’t feasible and I can’t recommend them.

But AI desperately needs to be fixed before it can do serious damage. And the only way for it to be fixed where it is right now is if it’s broken further.

Get Our Best Stories!

Sign up for What’s New Now to get our top stories delivered to your inbox every morning.

This newsletter may contain advertising, deals, or affiliate links. Subscribing to a newsletter indicates your consent to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. You may unsubscribe from the newsletters at any time.