Hollywood writers went on strike to protect their livelihoods from generative AI. Their remarkable victory matters for all workers.

April 2024

Growing up in a working-class immigrant family in Queens, N.Y., Danny Tolli dreamed of a career in television. “I was a storyteller straight out of the womb,” Tolli told me in November. After studying film and television at New York University, he worked his way up in Hollywood, starting out as an assistant a decade ago and rising to a TV writer and co-executive producer today.

Until last year, Tolli—like most of us—never imagined that artificial intelligence might threaten his career. For decades, automation has concentrated in the kinds of routine, blue-collar jobs he grew up around. Highly creative and cognitive roles—like writing the stories that shape our culture—were considered to have a low risk of disruption.

OpenAI’s release of ChatGPT 3.5 at the end of 2022 turned that paradigm on its head. Seemingly overnight, the generative AI chatbot captured the public’s attention by excelling at precisely the kinds of non-routine skills that have long been considered quintessentially “human.”

“It’s scary…We were watching in real time how it was starting to generate ideas, storylines, and scenes,” said Tolli. He pointed to one of AI’s defining features: its rapid expected increase in capabilities. “It’s not doing a great job 1712949996, but ChatGPT 6 might do an even better job,” he said.

Workers and AI: Voices from the front lines of disruption

In this ongoing series, Brookings Metro introduces you to workers in occupations that will likely face disruption from generative AI, including writers, legal assistants, illustrators, accountants, and customer service representatives.

In their own words, these workers will share what they feel is at stake as well as the risks and opportunities AI presents. Their stories are accompanied by in-depth case studies exploring AI’s effect on these industries and what policymakers, employers, and each of us can do to enable workers to benefit from AI and avoid potential harm.

Meet the Hollywood writers: Danny Tolli, co-executive producer; Leah Folta, TV story editor; David Goodman, executive producer; Raphael Bob-Waksberg; Showrunner; Jackie Penn, TV writer | Photo credit: Phil Cheung and David Walter Banks

For the first time, Tolli worried that Hollywood studios would use the new technology to replace writers and destroy the ladder he had been climbing. A lot was suddenly at stake: a career he felt he was born to do, the economic security that eluded his parents, and the kind of American Dream that had long been possible for successful Hollywood writers. Also at stake was the greater diversity and inclusion reflected in the newest generation of Hollywood writers, and the kinds of stories they could tell.

As Tolli’s fears grew, his union, the Writers Guild of America West, was in the middle of negotiating a three-year contract with the biggest studios in Hollywood. In just a matter of months, AI’s potential threat shot from obscurity to rallying cry for Tolli and thousands of fellow writers who went on strike in spring 2023. Among their list of demands were protections from AI—protections they won after a grueling five-month strike.

The contract the Guild secured in September set a historic precedent: It is up to the writers whether and how they use generative AI as a tool to assist and complement—not replace—them. Ultimately, if generative AI is used, the contract stipulates that writers get full credit and compensation. The victory was important for Tolli, but its implications reverberate far beyond Hollywood.

Reflecting on the strike, Tolli said:

With AI a central issue in our contract negotiation, we felt very much like the canary in the coal mine. That we were announcing to all workers and union members across the country that if these studios are going to use automation to replace screenwriters, what’s stopping them from taking your jobs?

Over the past several months, I interviewed Tolli and other Hollywood writers to document their fears and aspirations surrounding generative AI’s impact on their careers, and capture their stories from the front lines of this issue. (You can read more of their stories here.)

This report explores what is at stake for both writers and our society, what these writers were able to achieve in their contract negotiations, and what we can learn from this experience in terms of shaping the way AI is deployed in our economy. That Hollywood writers became the first and most visible face of resistance to generative AI speaks volumes about the nature of this new technology and the kinds of livelihoods that it will impact most. Their victory in securing first-of-their-kind protections offers important lessons for other unions and professional organizations, policymakers, and workers across a range of occupations who may face similar disruptions to their careers.

Danny Tolli, co-executive producer | Photo credit: Philip Cheung

Hollywood writing: A coveted career under strain from technology-driven shifts

A successful career writing in Hollywood has many hallmarks of a “dream” job: coveted, well paid, and exciting. Writing jobs in Hollywood are highly sought after and extremely competitive, if also unpredictable.

Leah Folta, a TV writer and story editor, reflected on the personal significance of her craft:

I love writing. I love all of it: the producing, the collaborating in the room, the way you get to exercise the muscles that we have in production and making sure things are executed the way you want. It is such a huge gift and so much fun. I don’t have a backup career, because I never wanted any.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, writers and authors in the motion picture and video industry earned an average annual wage of $136,690 in 2022, compared to an average of $61,900 for all job occupations in our economy. But pay varies widely by seniority and role, and Hollywood writers operate like independent contractors, seeking TV employment seasonally and selling movie scripts in a freelance fashion. Writers contend with rejected scripts, canceled shows, and periods of unemployment.

Minimum pay for Hollywood writers is negotiated by the union: the East and West branches of the Writers Guild of America (WGA). The WGA represents approximately 11,500 TV and movie writers and bargains on the sector level—meaning with all the major studios as a group, not company by company—through the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers (AMPTP). The AMPTP represents more than 350 film and television producers, including major studios such as Amazon, Apple, Discovery, Disney, NBCUniversal, Netflix, Paramount, Sony, and Warner Bros. Discovery. The WGA negotiates three-year contracts with the AMPTP that stipulate base compensation, staffing, residuals (when a show or film is reused), and other terms of employment for their members.

Here’s how it works, starting with feature films as an example. Feature film writers are compensated based on the product, type of writing, and budget of the film. The highest minimum pay of just over $160,000 is for an original screenplay for a high-budget film, and just over half this amount for a low-budget film. The lowest minimum payments are for “polishes” (which are less extensive than a full script rewrite) and for having a story (a summary of a film idea, but not a full script) included in a screenplay. Established screenwriters can command compensation that substantially exceeds these minimums rates.

Writing staff on TV shows are paid a weekly rate, by role, for a set number of weeks corresponding to a show’s season. The lowest-paid writer in the union—the staff writer—earns a minimum of $4,362 per week before fees and taxes. A writer-producer could earn about twice as much, and higher-ranked roles earn even more.

While early-career writers may struggle to make ends meet, traditionally, the most senior writers who have ascended the career ladder in film and television have been well compensated.

David A. Goodman, a TV writer with 35 years of experience and credits that include executive producer of “Family Guy,” underscored the arc of his good fortune when compared to that of the single parent who raised him on a modest income.

Certainly, when I entered the business [in 1988], if you could establish yourself as a writer in Hollywood, it led to a comfortable lifestyle. The pay was good. If you could continue to get work, you would get promotions and pay increases. It allowed me to have a life that was a much more comfortable one than I had a child. I was raised by a single mom who was a social worker in New York…There was a lot of financial anxiety in my family.

Goodman’s career allowed him to buy a home in Los Angeles, send his children to private school, take annual vacations, financially support struggling family members, and consistently pay his bills. He credited the WGA with enabling his longevity in the industry and providing stability during cyclical periods of financial difficulty.

In addition to union-provided health insurance and retirement benefits, Goodman cited the importance of residuals, which the union championed in successive contracts. Residuals are financial compensation paid out when a TV show or film is “reused,” such as through syndication, cable reruns, or licensing to a streaming platform. Goodman said that during periods of unemployment after a canceled shows or between seasons, residual checks would occasionally appear in the mail and help him keep his family afloat and continue to pay his bills until he was able to secure his next writing job.

Disruptions from the advent of streaming

Over the past two decades, the stability and compensation that have defined the careers of established writers like David A. Goodman have been eroded by disruptions from the advent of streaming, which now accounts for about half of TV writing employment.

Compared to traditional network TV, the streaming platforms such as Netflix and Amazon Prime Video typically offer writers fewer episodes per season, fewer weeks of employment, smaller paychecks, less financial reward through residual payments when shows are successful, and smaller writers’ rooms with fewer jobs. Pay has eroded: In recent years, half of TV writers earned the minimum compensation as laid out in the union agreement, up from one-third of writers in the 2013-14 season.

During the height of network TV, a show like “Seinfeld” would air 22 episodes per season and provide upward of 40 weeks of work for writers. In comparison, a popular streaming show like “Bridgerton” airs just eight episodes per season and provides fewer weeks of employment for writers.

In addition to fewer weeks of guaranteed employment, streaming platforms have also shrunk the number of writers hired for many shows. TV writers in Hollywood typically work collaboratively in a “writers’ room,” which can vary in size from two to 20 writers. While a dozen writers staffing a writing room was common in the era of broadcast television, studios today have downsized, and some have introduced “mini-rooms” with just three or four writers.

Finally, the pivot toward streaming has disrupted the model of residual compensation. Popular shows and films that are “reused” provide writers a source of sporadic payment through residual checks—an important source of financial stability for writers between jobs, and representing a share of the financial success of their shows. The business model of streaming disrupted the residuals model, as streaming platforms can keep a film or show on their platform indefinitely and not license or sell the episodes—undermining a key source of stability and compensation for writers.

These changes have impacted writers at all levels (especially newer writers), and increased barriers to steady employment and a comfortable living. These disruptions have coincided with mounting headwinds facing the industry, including cost-cutting pressure from investors in streaming platforms who are pushing a shift from focusing mainly on subscriber growth to achieving profitability, as well as increasing competition for moviegoing audiences from at-home entertainment (including streaming) and social media.

Leah Folta, TV story editor | Photo credit: Philip Cheung

Generative AI: What is at stake for Hollywood writers

Against this backdrop of technology-driven shifts from the advent of streaming, the launch of ChatGPT at the end of 2022 ushered in a substantial new source of technological disruption—and anxiety—for writers in Hollywood.

ChatGPT popularized “generative artificial intelligence”—a type of machine learning. Generative AI works as an algorithm that can produce a wide range of new content, including creative content such as images, music, text, audio, and video. The technology is enabled by large language models (LLMs) that train on vast data sets, detecting statistical patterns and structures that it then uses to generate new content. For example, generative AI can train on thousands of existing TV or movie scripts to produce scripts based on ideas, dialogue, types of characters, and even plot developments that appear to work well together. This is the “generative” in generative AI: It creates, often with astonishing speed.

Zooming out from screenwriting to consider the job economy as a whole, generative AI’s capabilities represent a sharp departure from previous technologies. For decades, technology has been “skill-biased”: it has substituted for routine skills (such as calculating expenses, filing documents, or connecting parts of a vehicle on the assembly line), and complemented non-routine skills (such as managerial decisionmaking, complex analysis, and the use of human creativity).

Take law firms, for example. In recent decades, skill-biased digital technologies have substituted for some of the routine work legal secretaries perform, such as typing, filing, and transcribing. On the other hand, the technologies have complemented the skills of the lawyer through better tools for legal research and communication, leading to a sizable reduction in the ratio of legal secretaries to lawyers.

Previously, the legal industry was forecasted to have among the lowest risks of automation. In a widely cited 2013 paper, Oxford academics Carl Benedikt Frey and Michael Osbourne noted the low projected automation risk for lawyers:

For example, we find that paralegals and legal assistants—for which computers already substitute—in the high risk category. At the same time, lawyers, which rely on labour input from legal assistants, are in the low risk category. Thus, for the work of lawyers to be fully automated, engineering bottlenecks to creative and social intelligence will need to be overcome, implying that the computerisation of legal research will complement the work of lawyers in the medium term.

ChatGPT upends this paradigm. Generative AI has excelled at many of the non-routine skills that just a few years ago experts considered impossible for computers to perform, including creativity and empathy.

Consider law again. Today, the legal industry is among those with the highest exposure to AI. In 2023, ChatGPT 4 made headlines by passing the bar exam with a score higher than 90% of human test- takers. According to a forthcoming Brookings Metro analysis of data from OpenAI, lawyers could harness existing generative AI technology to save at least half the time on more than 80% of their core tasks, including conducting legal research, preparing briefs and opinions, and reviewing legal documents.

The emerging capabilities of generative AI will have a similar impact on creative industries. As discussed above, until recently, technology was considered a complement, not a substitute in creative fields such as writing. While a writer might have used a computer to format or spellcheck a document, the imagination, creativity, and writing skills underpinning storytelling have long been considered uniquely “human” and at low risk of automation. But as generative AI advances, this is no longer true. In a forthcoming Brookings analysis, my colleague Mark Muro uses data from OpenAI to forecast that writers and authors are 100% exposed to generative AI (the highest possible exposure score), while poets, lyricists, and creative writers are 88% exposed. Those figures mean that using generative AI could save at least half the time spent on 100% or 88% of those occupations’ tasks, respectively, as they are defined by the Bureau of Labor Statistics for all occupations.

So, what will this mean for “AI-exposed” workers such as screenwriters and lawyers? It’s not yet clear, but we can outline some possibilities. A high AI exposure score does not necessarily mean that a job will be automated or displaced. It could also mean the job might be augmented by making workers in those roles more productive, more capable, more creative, or more efficient as they carry out tasks. For instance, an advertiser using generative AI might be able to create highly personalized ads, while an architect could instantly build a model for a client.

Whether AI will augment or automate—and whether and how much workers benefit from those gains—is not preordained. It depends on the choices of consumers, investors, employers, and technologists; the capabilities of the technology; the demand for workers’ skills; and the existence—or lack—of guardrails to protect workers.

The potential to augment the work of screenwriters

For some writers, generative AI may present the possibility of assisting them in the development of scripts and with the daily activities associated with the job. Generative AI might help writers brainstorm plot ideas, draft dialogue, spark new ideas, write outlines, conduct research, create characters, summarize notes, or think of new plot twists. Generative AI might also expedite tasks that writers consider time-consuming or tedious. For instance, a writer who doesn’t enjoy writing summaries might leverage generative AI to assist and save time.

For highly creative and talented Hollywood writers, the emerging scholarly evidence suggests limits to these benefits, and even potential threats. Several recent studies document that generative AI’s biggest gains benefit less skilled and creative writers, essentially “leveling the playing field.” For instance, a 2023 paper by Anil R. Doshi and Oliver Hauser found that while generative AI did not measurably enhance the creativity of already highly creative writers, it did improve the writing of participants who were less creative, leveling out differences between the two tiers. These findings suggest it may not be the most capable and experienced professional writers who benefit most from the technology, but rather less experienced or less talented amateur writers who might harness AI to create scripts that are closer in quality to those written by highly skilled, seasoned professionals.

The potential to replace writers

Conscious of how relentlessly companies can focus on cutting costs, including labor costs, to drive up profits, Hollywood writers have reacted with skepticism that studios will use AI as a tool to enhance their creativity and job quality. Instead, there is widespread fear that studios will use it mainly to replace writers and maximize profits, even at the expense of the quality of the work.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg, the creator and showrunner for BoJack Horseman, explained this concern::

If you were to take a technology like this and say, ‘We’re going to give this to artists and make their lives easier and make their artistic power even greater,’ I would say, ‘Oh, that’s really interesting.’ But I don’t trust the companies to do that…When you look at the larger applications of these technologies, companies and studios never want to use it to empower artists to make cooler stuff for the same amount of money. They want to make things cheaper, cut the artists out, pay people less, and use these technologies in a way that doesn’t make the work better.

While current versions of generative AI software can now autonomously generate an entire script, the quality is still rudimentary. This has provided little comfort to David A. Goodman, who expressed grave concerns about the potential threats to writers’ livelihoods as the technology improves:

In the long term, as this technology improves, I don’t think there are any limits to what it might be able to do. My imagination is limited, but I am experienced enough to know that just because I can’t imagine something, doesn’t mean it can’t happen. I do feel that this technology is impressive. At some point it could literally generate what are seemingly original scripts…It’s very scary. As soon as the companies can get rid of writers, they will.

In the nearer term, one major concern for Hollywood writers centers on truncating creative human work: Some TV writers fear that studios’ use of generative AI for drafting scripts could eliminate the writers’ room, effectively wiping out most TV writing jobs. Specifically, studios may develop the technical capacity to replace some writing jobs by generating first drafts of scripts with AI using their own copyrighted material. For instance, a studio that has a long-running procedural show with established characters and a formulaic storytelling style—like “Law and Order” or a vault of princess movies and superhero franchises—could train an AI model on its existing scripts and generate a first draft of a new episode or film.

The potential to degrade jobs and exacerbate financial insecurity

On top of possible job losses, another concern is that studios’ use of AI could transform and degrade the writing jobs that remain. Many writers fear that as studios use generative AI to create the first draft of TV or movie scripts, the few writers they hire will only polish and edit those AI-generated drafts—with sweeping consequences not only for the number of jobs, but for writers’ compensation and the nature and quality of their work. Fundamentally, the writing role could shift from writing and creating original ideas to editing AI-generated scripts, with less creative input and significantly less pay.

Danny Tolli noted:

A big concern for me is AI generating ideas and scripts, and writers only being hired for polishing and rewrites. We won’t be writers anymore. It is quite depressing and scary…Basically, we just become gig workers in an industry where we were an instrumental part of creating the product. It’s like the Uber-fication of Hollywood.

Writers have a lot at stake financially from these shifts. In films, a rewrite of a screenplay commands just over one-quarter of the minimum payment for writing an original screenplay. In TV, the guaranteed employment of writers’ rooms could be replaced with just a few days or weeks of work for a writer to rewrite a script, at a fraction of the pay.

Fewer weeks of employment and smaller paychecks would make it much more difficult for writers to support themselves—upending what is currently a financially viable career for many people and putting pressure on them to cobble together more jobs to make ends meet. Less reliable employment would also make it more difficult for writers to qualify for union-provided health insurance and limit their retirement contributions, further undermining financial stability. Ultimately, as writers face increased barriers to secure employment and financial stability, fewer writers—especially newer writers—may find they are able to continue in the profession.

The potential to undermine the career ladder for newer writers

If the use of generative AI results in smaller writers’ rooms or eliminates them altogether, it would upend the structured career ladder that has defined TV writing in Hollywood for decades. Historically, if writers secured roles in successive seasons or on new shows, they typically ascended the following hierarchy and gained valuable experience, mentorship, credits, and on-the-job training via each successive role, in one of the most successful apprenticeship systems in our economy.

TV writing career ladder

Source: WGAW, Medium Filmarket Club, and Screencraft

In addition to the roles above, which are represented by the WGA, TV writing is also supported by entry-level roles such as writers’ assistants and personal assistants, which often provide a springboard to staff writing positions with union representation.

An animating concern for many Hollywood writers is the fear that studios’ use of generative AI to draft scripts could wipe out the writers’ room—and with it, the career ladder and opportunities for newer writers. Danny Tolli explained this concern:

AI is going to completely destroy the ladder to get to be a showrunner. You are completely wiping out the career trajectory. You’re essentially saying that showrunners will be the only ones working. We’re not going to be training the future generation. If the younger generation is not getting the necessary experience, there is no way the company is going to give a showrunning opportunity to a writer who has no credits on their resume.

The use of generative AI to automate administrative tasks could also undermine career advancement for aspiring writers. Proponents often tout the productivity benefits of generative AI taking over routine tasks and “freeing up” workers to shift to more strategic, analytical, creative, and interpersonal work. In Hollywood, however, entry-level administrative roles are valuable starting points that enable aspiring writers to get a foothold in the industry and gain critical experience. Tasks that might seem like “drudgery” and ripe for automation—taking meeting notes, tweaking scripts, transcribing edits—are instrumental to an early-career writer’s ability to hone skills, build a network, get mentored, and learn the inner workings of the industry task by task and project by project.

David Goodman, executive producer | Photo credit: David Walter Banks

Generative AI: What is at stake for society

The use of generative AI in scriptwriting raises many issues for society, from ethical concerns to questions of who gets to tell the stories that define our culture, what kinds of stories are ultimately told or not told, and their quality and impact.

Diversity and the stories that are told

The use of generative AI in Hollywood scriptwriting could undermine the recent progress made in Hollywood to diversify the ranks of its storytellers. Since Hollywood started making movies, the writers it has hired to tell stories have reflected a narrow demographic, with white men dominating the industry. Even as recently as 2022, nearly 60% of all showrunners (the top TV writing position) were white men.

Over the last decade, and particularly after the racial reckoning following George Floyd’s murder in 2020, the industry made a push for more inclusive hiring to strengthen the diversity in its ranks. These shifts reflect a growing awareness of the impact of diversity on the types of stories that are told, the perspectives and communities that are reflected, and how viewers see themselves and the world around them as a result.

Thus far, these efforts are mainly visible in the lower rungs of the writing profession, reflecting the greater diversity of new hires over the past decade. For instance, the percent of new hires that identify as women, BIPOC, disabled, or LGBTQ+ increased substantially in the past five years. The contrast between entry-level roles and the most senior is stark: Over 80% of entry-level staff writers were women and people of color in 2020, compared to only about one-third of executive producers.

Change in diversity of TV writers, 2011–2020

Source: Writers Guild of America West

Generative AI-drafted scripts also risk reinforcing existing biases and the lack of diversity in Hollywood’s past writing. TV writer Jackie Penn raised her concern that training AI models on existing scripts could marginalize the voices of diverse writers and the perspectives of different communities.

Societal concerns about the quality of AI art

The specter of AI creating movie scripts—along with other forms art and culture—raises existential and ethical questions for society. If creativity is “an expression of our humanity,” what will it mean for society if stories are generated by a computer? What will it mean for society if AI makes it harder for artists and writers to earn a living, and many stop doing so?

Echoing concerns from prominent authors and creatives, some Hollywood writers have raised ethical concerns over the training of large language models on the (often copyrighted) works of artists, without consent or compensation—threatening their livelihoods in the process. Screenwriter Cheryl Guerriero told me that it feels like plagiarism to her, and she doesn’t understand how it can be allowed.

Another key concern for society is whether AI-generated writing and art will be any good. This is especially pertinent to the use of AI for writing in Hollywood; the industry’s movies and shows are consumed by billions of people around the world and have an outsize cultural influence.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg raised concerns that AI will lead to what economists Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo call “so-so technology”—i.e., advances that do not enhance quality or productivity, but negatively impact jobs:

I love TV, I love movies, I love stories, I love good writing. I want there to be more good stuff and less bad stuff. And when I look at AI-generated art, it isn’t very good. I worry that it could get good enough and close enough that it drowns out the marketplace, and it is cheap enough that the companies rely on it more and more in a way that makes it not feasible for actual writers and artists to be paid to create stuff. I just think we’ll be so much worse off as a culture for that…I think stories are good because people have observations about life that they’re trying to express, not because they’re running through a series of language tricks they know make for digestible sentences.

For many writers, the inspiration for their characters or stories comes from personal experience: from real people in their lives, from emotions they have felt, from experiences that gave them unique human insights that they can connect to an audience. Some have questioned whether a computer can give a story emotions as effectively as humans can. David A. Goodman reflected on this potential loss of connection when AI writes stories.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg, Showrunner | Photo credit: Philip Cheung

The labor strike and groundbreaking contract: What was achieved—and how

The Writers Guild of America’s victory in securing historic protections from AI in its 2023 contract was in many ways an unlikely success story.

At the end of 2022, when the WGA leadership first began setting priorities for the negotiation of the next three-year contract, the issue of generative AI was not even on the list. While a few forward-looking board members were vocal about their AI concerns, early on, the union’s priorities centered on bread-and-butter issues such as minimum payments, residuals, and staffing size.

That changed abruptly by early 2023, as awareness of ChatGPT’s capabilities spread following its release. David A. Goodman, who served as a co-chair of the union’s negotiation committee during the 2023 strike and is a past president of the WGA, described how in just a matter of months, AI rose from being almost completely off their radar to one of the most important issues for their membership:

It was during that negotiation process in the late winter and early spring [2023] that we really started to realize this was something we were going to have to deal with in this negotiation right away. It all happened very quickly…[ChatGPT] entered the zeitgeist in a way that writers themselves became aware of it. Suddenly it went from nobody talking about it to everyone talking about it. People started using ChatGPT in casual ways and were just so impressed by it. Then people with imagination recognized, ‘Wait a second, if this gets better, can this actually replace writers? Can the companies use this to generate scripts that are good enough to produce and cut writers out of the process entirely?’ That was the fear. And it snowballed in such a way that whether this was a possibility in the short term or not didn’t matter. People’s imaginations saw this. The people working on ChatGPT were adding to that by touting, ‘This thing you’re seeing now, it’s not even half as good as the next generation.’ That made things even more dire from a writer’s point of view.

Goodman credited the union’s leadership for their adaptability in quickly figuring out what specific AI-related priorities to include in the negotiations, which were already underway. In May, the WGA proposed several AI regulations, including that AI can’t “write or rewrite literary material, can’t be used as source material, and MBA [minimum basic agreement] covered material can’t be used to train AI.”

Initially, Goodman said the union leadership assumed AI was not yet an immediate risk to their careers, but they needed to build guardrails into the contract for the future. This perception shifted when the alliance of studios (the AMPTP) categorically rejected the WGA’s proposed regulations and countered with annual meetings to “discuss” advancements in technology.

By law, the AMPTP had the right to refuse to bargain over the use of a technology like AI—an authority due to federal labor law’s designation of technology as an issue of “managerial prerogative” outside the required purview of collective bargaining. For months, the studios refused to come to the table to discuss AI.

While within their legal purview, the studios’ refusal to bargain over AI may have been a strategic misstep, which several studio executives later acknowledged. Their resistance sent a worrying signal to the writers about studios’ near-term intentions with AI and created solidarity among the writers—elevating the stakes of the negotiation from immediate concerns about compensation and staffing sizes to a new and existential threat to writers’ livelihoods.

A 148-day strike

In spring 2023, negotiations between the WGA and the AMPTP broke down. Nearly unanimously, guild members voted to authorize a strike, which began on May 2.

During the grueling, five-month strike, the existential threats posed by AI and streaming were a uniting issue writers rallied around through months of financial hardship and outdoor picketing during a record heat wave.

Leah Folta described the immense physical and mental toll of the strike:

I had no idea how hard it was to be on strike. It’s insanely difficult…The first month especially was such an emotional roller coaster. I know that in the version we had, everyone was very united. Everybody in our union and in our industry was united and on our side. The public was on our side. The majority of the press was on our side. And still, it was so hard. It is mentally and physically grueling. I had all of these background worries—I was one of the people whose health insurance was due to run out. June 30 was my deadline to make more money or lose my health insurance, and we started the strike in the beginning of May. I’m running out of money. Everyone around me is running out of money. It was scary and uncomfortable.

Despite the challenges of financial stress, uncertainty about the future, and picketing in the extreme heat, Folta said that the writers stayed united because the stakes were so high: “It was this existential, and this bad.”

Jackie Penn elaborated on the stakes:

Striking was one of the hardest things I have ever done. We showed up every day to show not only the companies, but the entire country, that we were really serious about these concerns to our livelihood…Being a writer is very hard already when you are trying to get compensated for your work. With AI potentially taking away jobs from writers, I think it was really important we fought to make sure we are in charge of how we use it, or if we use it, and not for it to be imposed on us. Our contract is only up every three years. It was important we held the line because of how things are going to develop with AI. Three years would have been too late.

As the strike wore on through the hot summer, the writers were buoyed by the presence of other workers from the entertainment industry who joined them on the picket line, including behind-the-scenes workers from the Teamsters and International Alliance of Theatrical Stage Employees (IATSE). On July 13, the Screen Actors Guild-American Federation of Television and Radio Artists (SAG-AFTRA) announced their own strike—the first time that writers and actors had simultaneously gone on strike since 1960.

The overlapping strikes brought heightened public attention to the plight of the actors and writers, raising the visibility of their shared concerns from residuals and compensation to the existential threats from AI and streaming. The strikes drove extensive media coverage: According to our search of Meltwater’s media tracking platform, more than 18,000 media stories were written about the writers’ strike between May and September. The actors’ strike further shut down Hollywood production and ratcheted up financial pressure on the studios, while drawing public attention as the filming of popular shows and movies was halted and highly anticipated film releases were delayed.

After months of impasse, momentum finally shifted in mid-September, when studio bosses and labor leadership met in person for the first time. In an unusual move, four studio CEOs attended the multi-day meetings at the WGA headquarters beginning on September 20. The presence of executives such as Disney CEO Bob Iger and Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David Zaslav reflected a new urgency to reach a deal and mounting financial pressure on the companies. The intensive negotiations yielded breakthrough progress, and a tentative deal was announced within days.

A historic contract with new guardrails on AI

After 148 days, the second-longest strike in the WGA’s history ended on September 26, 2023. The contract was heralded widely as a major victory for the writers. It includes significant concessions along all the key pillars of the negotiation, including residual payments, minimum staffing, compensation, and benefits.

But the contract also includes far-reaching guardrails on generative AI—the first of their kind for any collective bargaining agreement. The contract does not outright ban the use of generative AI, but rather, regulates its use in ways that could benefit writers and studios and reduce harms.

The contract explicitly spells out that AI is not itself a writer competing with humans, but rather a tool for writers’ beneficial use. To the extent that AI is used, the regulations specify that AI should complement the work of writers instead of replacing them. The contract permits studios and writers to use generative AI under specific circumstances, but with guardrails that protect writers’ employment, credit, and creative control, while also protecting the studios’ copyright.

More specifically, the 2023 contract includes the following AI regulations:

- AI is not a writer. The contract specifies that “neither traditional AI nor GAI [generative AI] is a person, neither is a ‘writer’ or ‘professional writer’…and, therefore, written material produced by traditional AI or GAI shall not be considered literary material”—i.e., written products that writers create, including stories, treatments, and screenplays. The implication of this is that only writers will be given credit for writing, even if generative AI is used; generative AI itself cannot be credited with authoring original material. This is an important win for writers, and also helpful to studios to safeguard their copyright.

- Writers have agency: They can choose to use generative AI in their writing process, but cannot be forced to do so by the studios. The contract specifies that writers can use generative AI with the company’s consent, but “a Company may not require a writer to use ChatGPT to write literary material.”

- Under certain terms, studios can provide writers with an AI-generated draft, but it does not count as “source material”—meaning writers get full credit and compensation for originating the idea. This set of guardrails addresses writers’ concern that studios’ use of AI-generated drafts will undercut their compensation and credit. (A rewrite of a draft, for instance, commands just over one-quarter of the minimum compensation for drafting an original screenplay, while a “polish” is paid even less.) The contract stipulates that writers will get the same credits and compensation for working off an AI-generated draft provided by the studio as they would if they came up with it as an original idea and written it from scratch.

- Studios can set AI policies and reject the use of AI when it undermines copyright. This regulation allows companies to determine AI policies and addresses studios’ concerns about the potential for AI to infringe on their copyright or intellectual property, as well as other concerns related to ethics, privacy, and security.

- The specific terms of the use of copyrighted material to train AI models remain unresolved. Writers reserve the right to prohibit the training of generative AI with their written work. This clause addresses writers’ concern about studios’ training their AI models on screenplays and scripts that writers have authored, but whose copyright is owned by the studios. The contract does not adjudicate this concern, but preserves the studios’ and union’s right to negotiate over these legal and regulatory issues in the future.

While the safeguards and regulations are designed to benefit writers and studios, society and future viewers may also win. The contract creates incentives for writers to experiment with generative AI on their own terms, find use cases that are helpful to their writing process, and improve the quality of the output, while ensuring that the writers share in the benefits of those gains. At the same time, the contract disincentivizes studios from cutting costs by turning to AI to generate poor-quality drafts. Because the contract stipulates that studios pay writers the same compensation if they work off an AI draft provided by the studios or if they write the script from scratch, studios are incentivized to use generative AI when it might improve the end product, but not simply as a means to cut labor costs at the expense of quality.

Key ingredients for success

The writers’ success was bolstered by numerous factors:

- Solidarity with other unions, and the simultaneous actors’ strike. The striking writers were buoyed by strong support from other unions that spanned markedly different industries. In addition to solidarity with SAG-AFTRA members, the writers benefitted from solidarity and support from other local unions in the entertainment industry, including the crew union IATSE and the Teamsters Local 399, whose members were involved in coordinated actions to shut down Hollywood productions. The writers were also aided by vocal support from the biggest unions in the country, including the AFL-CIO, and by workers representing a diverse cross-section of society: teachers, nurses, hotel workers, Starbucks baristas, and other union members all joined the picket line.

- A post-pandemic reckoning. The writers’ grievances resonated with a broader post-pandemic reckoning around income inequality and how corporations treat workers. These were reflected in a wave of strikes and labor unrest in 2023 spanning numerous industries: autoworkers, Starbucks baristas, Kaiser Permanente health workers, Washington Post journalists, and UPS drivers and package handlers. At another time, the public may have perceived the writers’ grievances as self-interested compensation demands from an elite group. Instead, the writers tapped into the national zeitgeist and connected their plight to broader public concerns about corporations prioritizing profits over workers, AI’s threat to jobs, and the degradation of job quality.

Leah Folta reflected on this national mood:

Income inequality was already so bad. We’ve seen so much corporate consolidation and so much wealth transferred upward. When the pandemic started, and we had this huge disruptive event, it seemed like a lot was being rethought at the same time that the transfer of wealth from workers to the very few people at the top accelerated. I think the business model of a huge corporation valuing its stock more than doing business well or treating its workers well is in every part of our country right now. We are finally at a point where it is so bad that everyone’s ready to band together and fight it. Nobody wants to spend our time doing this. It’s not fun. It’s because things have gotten so bad.

- Shaping public opinion. The writers effectively harnessed their creativity and writing talents to shape the story of the strike and influence public opinion. In particular, they successfully leveraged social media: sharing selfies, videos, messages, and humor to garner publicity and sympathy during the strike. The writers were also effective in framing studio executives’ critical comments about their demands as cruel and out of touch—contrasting these comments unfavorably to the CEOs’ lavish pay packages. As the strike wore on, it was clear that public support skewed strongly in favor of the writers rather than the studios: 72% versus 19%, according to an August 2023 Gallup poll.

- An alignment of interests around copyright. In securing AI protections, the writers benefited from the studios’ shared interest in protecting copyright. The U.S. Copyright Office has determined that only works authored by a human can be copyrighted: “In the Office’s view, it is well-established that copyright can protect only material that is the product of human creativity. Most fundamentally, the term ‘author,’ which is used in both the Constitution and the Copyright Act, excludes non-humans.” Under this interpretation, the interests of writers and studios align: A human writer needs to be involved in creating written stories in order for the works to be copyrighted by law, which in turn protects studios’ financial interests. This confluence of interests is somewhat unique to a narrow set of industries in entertainment, creative arts, and writing, where copyright is a salient concern for employers. Workers seeking protections in most other industries that generative AI will disrupt—from customer service to law, finance, computer programming, clerical work, and education—may face a more challenging battle in securing similar protections without this mutual interest between content owner and producer.

- Leverage—workers are indispensable, for now. In negotiating with the studios, writers continued to wield their most basic source of leverage as workers: their creative talents. Even with recent advancements in generative AI, studios cannot succeed today without the talents of the writers.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg reflected on this leverage and timing:

Right now, we’re at a place where if we say, ‘It’s us or the machines,’ they’re going to pick us because they know the machines aren’t good enough to completely replace us right now. This is the time when we have the leverage and the power to get some of this into our contract before it’s too late. And not rely on the studios believing in the greater good or believing in our rational arguments that that this would be better, but to actually just exert our power and make them listen. And that’s what we did.

- Economic hardship, culpable villains. While studios may have assumed that writers’ strained pocketbooks were a source of leverage, they may have underestimated the extent to which it was also a source of an inspiration and solidarity. In an anonymous comment to the media, one studio executive highlighted the (unsuccessful) strategy of prolonging the strike until writers run out of money as a way to gain leverage: “The endgame is to allow things to drag on until union members start losing their apartments and losing their houses.” But in the end, the increasingly precarious nature of their writing career fueled writers’ motivation to fight for a better contract—and it provided many writers with the training to weather a prolonged strike, including experience finding second jobs and side hustles to make ends meet. As the anonymous executive’s comment underscores, the mere suggestion by a studio executive that the goal was to drive workers into hardship also reinforced the workers’ preferred moral narrative of the strike and garnered more public sympathy for their cause.

Jackie Penn, TV writer | Photo credit: Philip Cheung

Lessons for other unions and workers in industries poised for AI disruption

The writers’ success in securing historic AI protections dispelled the narrative of inevitability that often frames discussions around AI and work. By exercising their power, the writers pushed back and succeeded in setting their own terms for the use of AI. Their success has far-reaching implications for workers across many other industries—and not just those in the creative arts, but also in knowledge work, STEM careers, customer service, clerical work, and sectors such as law, finance, and journalism. That said, the implications are greatly complicated by the fact that these are mostly non-unionized occupations.

There are several important lessons for other unions, and AI-exposed workers generally, in the WGA’s approach and ultimate success:

- The agreement offers an historic precedent as well as a blueprint. The WGA agreement set an important precedent about the possibility of collective bargaining over the use of AI. The contract proves that it is possible for unions to bring employers to the negotiating table for technology like AI—and the terms of the agreement provide a roadmap for other unions seeking similar protections. Importantly, in future contract negotiations, other unions can cite the writers’ agreement if employers refuse to bargain over AI, and look to the specific protections it provides as a guide.

- The contract reflects workers’ decision to shape—not ban—the use of a powerful new technology. The WGA’s approach of shaping the use of AI and its benefits—and not fighting to ban it—was instrumental to their success and a model for other unions.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg elaborated on this:

If we can have some protections where we, the workers, can control the automation, then the automation can be used to help us do our jobs. I don’t think anyone would be against that. We’re not saying we want to go back to the rotary phone. We’re not saying we want innovation to stop in its tracks. We’re saying we need to hold the keys. Because when companies hold the keys, we get cut out. And it’s devastating for communities, it’s devastating for families, it’s devastating for workers.

- The contract terms could facilitate bottom-up, worker-led innovations that benefit workers and employers. The guardrails in the contract protecting compensation, credits, and job security create an enabling environment where writers may feel “safe” to experiment with the technology and explore ways to enhance their job. Compared to other big-tech inventions, generative AI is especially amendable to “bottom-up” innovations. Through this experimentation, there are important lessons that can be learned from writers’ uses of AI, which can inform future development of these tools in ways that benefit workers.

Ultimately, this worker-driven experimentation is good for workers—and good for employers too. A growing body of research is documenting the benefits of incorporating end users (meaning workers in this context) into the design and roll out of new technologies, compared to top-down implementation. But most of us don’t need formal scholarly research to confirm that: Every white-collar worker who has suffered the confusing and frustrating roll out of “amazing” new software in their organization can attest.

With writers in the driver’s seat, generative AI may prove to be a helpful tool. This is also the case for workers across many industries—from paralegals to auditors, market research analysts, educators, and engineers—who may find productive and job-quality-enhancing uses of the technology if given the right opportunity to experiment, shape, and benefit from its use. A lesson from the writers’ contract is that it is possible to open the door to mutually beneficial uses of generative AI.

- The workers were proactive, not reactive, to looming technological change—acting before the horse had left the barn. Following ChatGPT’s release, WGA leadership moved with notable speed to formulate regulations and guardrails to protect their members. They did not wait until studios were harnessing the technology to take action. By taking a proactive approach, the union was able to shape the use of this new technology more or less from the beginning, and put in place contract terms for future negotiations. The writers should continue this proactive approach, taking advantage of the scheduled discussions with the studios to engage in a dialogue about AI well ahead of the next contract negotiations.

Other unions can learn from this forward-looking approach. Several have already moved quickly to develop AI positions, mobilize members, and negotiate terms of AI use in collective bargaining agreements. For instance, just months after the screenwriters and studios announced their historic agreement, the Communication Workers of America (CWA) published a set of AI principles and recommendations, including a proactive approach to educating their members and a comprehensive strategy for addressing AI concerns.

- Continued dialogue around AI outside of the collective bargaining process. Importantly, the contract specifies that studios and the WGA commit to semi-annual meetings, at the request of the union, to “discuss and review” the use and intended use of generative AI. These opportunities for semi-regular dialogue are important opportunities for continued monitoring and learning to ensure that technologies are deployed in ways that augment human creativity and share prosperity.

The need for policy reforms and new forms of worker voice and governance

In their pathbreaking approach to shaping the use of a new tool, the screenwriters reminded us of an old one: the power of unions and collective bargaining. The writers’ success was a clear vindication of collective action, and a reminder to a nation with very low rates of unionization, especially in the private sector, compared to other advanced economies.

Danny Tolli noted that what they accomplished as 11,500 writers standing together would never have been possible if he acted alone. Similarly, Leah Folta reflected:

I feel that unions are literally the only way for workers to protect themselves or make change in this day and age. There is such an imbalance between the giant companies we all work for and each individual worker. It’s the only protection we have…I feel so lucky to be in a union that is exercising its power and its leverage.

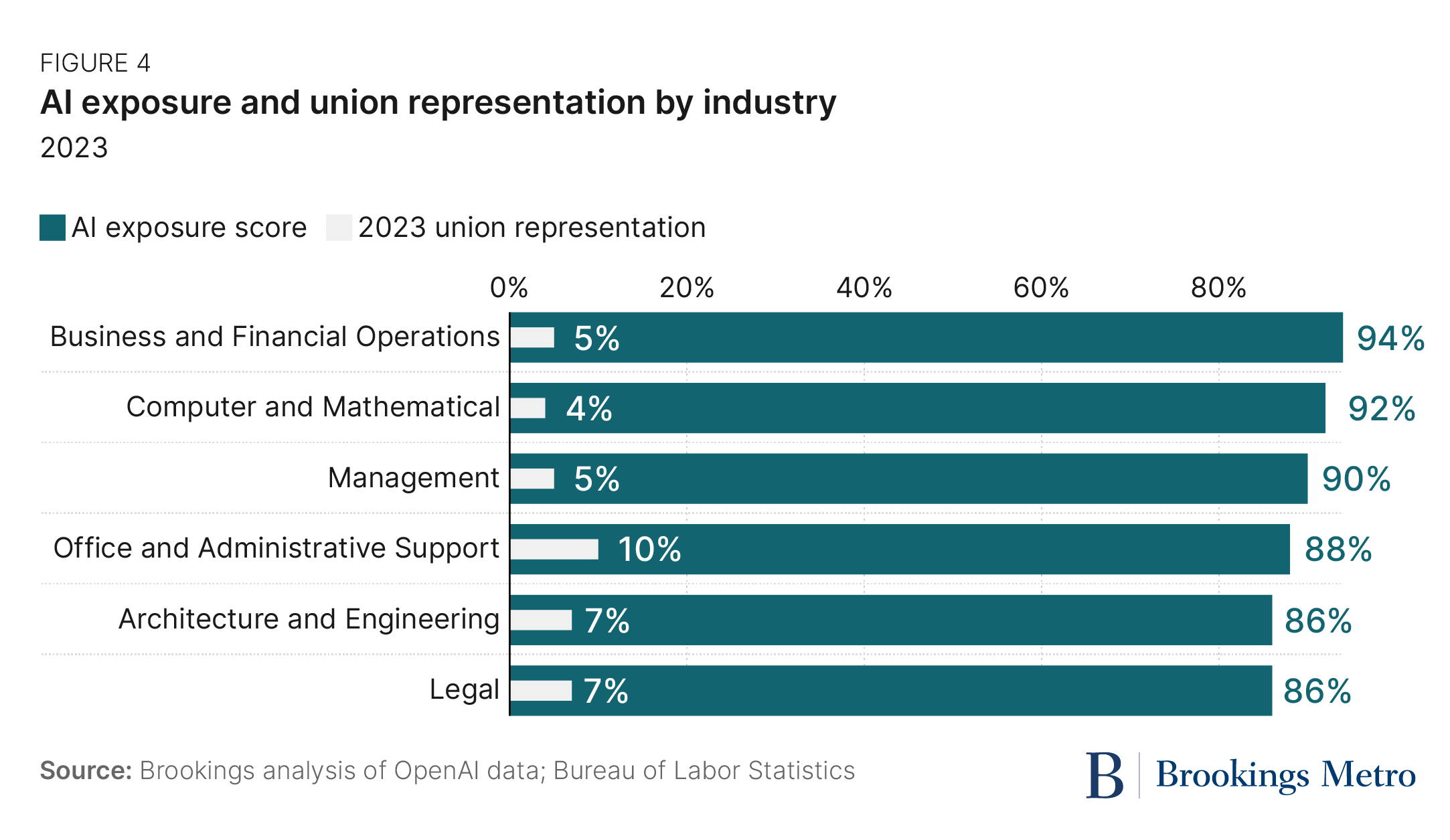

While historic, the replicability of the writers’ success in securing worker-friendly AI protections is limited in many of the industries that AI is poised to most disrupt. Nationally, 10% of workers and just 6% of private sector workers were represented by a union in 2023. In the top three industries with the highest AI exposure, unions represent an even smaller percentage of workers.

This low union density means that most workers whose jobs will be disrupted by generative AI will very likely not have the same ability as the Hollywood writers to bargain collectively or exercise real power in shaping the way AI impacts their livelihood. Even for those who are represented by a union, few will have the ability to bargain at the sector level (as opposed to the individual enterprise or workplace level), as the WGA did.

This mismatch between union representation and AI exposure underscores the importance of labor law reforms that enhance workers’ ability to exercise power and voice in their workplace, and even at the sector level. Today, labor unions are enjoying their highest public approval since 1965. Despite this soaring popularity, workers face an uphill battle in efforts to unionize, largely due to fundamental weaknesses in current labor laws.

Federal and state labor law reforms could level the playing field between workers and employers and give workers a stronger voice, including regarding AI. While proposed labor reform legislation at the federal level has languished in the Senate, progress in the near term might be possible at the state level. State governments are the nation’s most frequent and active labor regulators, albeit with huge variation between relatively pro-labor versus anti-labor states.

Labor law reforms are also needed to replicate some of the best examples of institutions of worker voice in other advanced economies, including those in Europe. Sectoral bargaining, which entails negotiating across an entire sector to create industry-wide standards, offers an impactful model of worker voice that can lead to more effective labor-management collaboration around technology. So does “worker co-determination” of how enterprises will produce—i.e., how work will be done, as distinct from how it will be rewarded. Works councils in Germany and Scandinavian countries give elected worker representatives an opportunity to influence the deployment of technology. The adoption of works councils and sectoral bargaining face numerous barriers, including requiring labor law reform, the cooperation of potentially reluctant employers, and overcoming resistance from some unions. The Clean Slate for Worker Power project at Harvard Law School has delineated several reforms and recommendations that could pave the way for works councils and sectoral bargaining. Absent broader reforms, new ideas should be explored, including AI-specific bargaining at the sectoral level.

With the limited reach of unions and absence of formal institutions such as works councils, workers will also need civil society organizations, policymakers, worker groups, and industry itself to play a role in creating new opportunities for worker voice, collaboration, and guardrails.

States have moved faster than the federal government in exploring legislation to provide AI protections to workers, especially around avoiding harms related to surveillance, bias, and data privacy. To date, there are few examples of legislation specifically addressing the harms of automation and its risk to livelihoods.

Workers in impacted industries can learn from campaigns such as Bargaining for the Common Good and Athena. Workers, policymakers, and concerned citizens can also learn from voluntarily adopted codes of conduct for “good” employers, and they can influence those with their buying and investing power, as nonprofit organizations focused on business reform such as JUST Capital and the Good Jobs Institute have shown.

However we motivate good employer practice—whether by formal rule, new industry norms reinforced by a watchful public and policy environment, or both—we have some emerging indicators beyond the screenwriters’ agreement of what it can look like. In new research on bringing worker voice into the deployment of generative AI, Tom Kochan and colleagues at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology cited the new tech-labor partnership between Microsoft and the AFL-CIO as an example of the new, collaborative forums needed to bring industry and workers together to adopt shared-gain—rather than zero-sum—approaches to AI. This includes work further upstream in how the technology is designed in the first place. For instance, the AFL-CIO’s Technology Institute has partnered with universities including Carnegie Mellon to bring workers’ perspectives and voices into the research and design of AI and other new technology products.

Conclusion

In some ways, the writers’ success reflects something of a best-case scenario. They were organized in a highly effective union, in a unionized industry, in a union town. They leveraged one of their greatest skills—their imagination—to project into the future and swiftly anticipate threats to their livelihood. As creators of popular shows and movies watched by millions of people, they enjoyed a visibility that other workers in similarly AI-exposed industries—such as paralegals, call center workers, bookkeeping assistants, engineers, and insurance underwriters—lack.

Even with this groundbreaking success, many writers remain anxious about the future. While historic, the contract they secured covers only the next three years, rendering the future uncertain as technological capabilities continue to advance. Many writers spoke frankly about the tension between corporations’ interest in maximizing profits and the security of their jobs. Shaping the future of their work will require vigilance, organizing, policy change, and attention from policymakers.

Raphael Bob-Waksberg reflected on the challenge ahead:

I think Washington should take this seriously. This is something that unites workers across all industries: the fear that automation is going to take over our jobs…I think we need to organize. I think it’s going to require unions. I think it’s going to require rallying politicians, and it’s going to require large groups of people working together. Obviously, you’re not going to stop innovation—that’s a foolish thing to hope for, nor would I want to. But I think you can create some guardrails around it and use political power and worker power to protect people.

What gives Danny Tolli hope for the future is the broad solidarity he witnessed during the strike, with workers banding together across industries as diverse as hospitality, health care, and manufacturing. Their victory was bigger than just one industry: It has already inspired worker mobilization and additional safeguards, and provided a blueprint for what is possible.

Acknowledgements

I am immensely grateful to the writers who generously shared their stories: Raphael Bob-Waksberg, Leah Folta, Cheryl Guerriero, David A. Goodman, Jackie Penn, and Danny Tolli. Special thanks to Leah Folta for her connections to many of the writers, to Becca and Matt Portman, Colleen Kinder and Brian O’Connor for their helpful introductions, and to Charlie Kelly for sharing his perspectives. Thanks to Phil Cheung and David Walter Banks for their excellent photography. Thanks to Leigh Balon, Alec Friedhoff, Michael Gaynor, and Carie Muscatello for their incredible creativity, talent, and collaboration in bringing the stories to life. Thanks to Glencora Haskins for her excellent work creating the visualizations in this report, to Benjamin Swedberg for fact checking, and to Erin Raftery for her promotion of the report. Thanks to Fred Dews, Gastón Reboredo, and Kuwilileni Williams-Hauwanga for their enthusiastic support in recording and transcribing the interviews. Thanks to Leigh Balon, Alan Berube, Xavier de Souza Briggs, Walter Frick, David Goodman, Glencora Haskins, Tom Kochan, Mark Muro, and Bharat Ramamurti for helpful feedback on the report draft.

This publication is part of a series on generative AI and workers made possible by support from Omidyar Network. The views expressed in this report are those of its authors and do not represent the views of the donors, their officers, or employees. Thanks in particular to Lauren Alexander, Anmol Chaddha, Laura Chavez-Varela, Anamitra Deb, Beth Kanter, Alexis Krieg, Mike Kubzansky, Michele Jawando, and Tracy Williams for recognizing the importance of worker storytelling and for supporting this series.

These interviews were conducted between November 4, 2023 and January 16, 2024. Participants have provided permission to Brookings to use their names, likenesses, transcribed words, and audio for this series. The quotes have been edited for clarity and brevity.