How A.I. Tools Could Change India’s Elections

For a glimpse of where artificial intelligence is headed in election campaigns, look to India, the world’s largest democracy, as it starts heading to the polls on Friday.

An A.I.-generated version of Prime Minister Narendra Modi that has been shared on WhatsApp shows the possibilities for hyperpersonalized outreach in a country with nearly a billion voters. In the video — a demo clip whose source is unclear — Mr. Modi’s avatar addresses a series of voters directly, by name.

However, it is not perfect. Mr. Modi appears to wear two different pairs of glasses, and some parts of the video are pixelated.

Down the ladder, workers in Mr. Modi’s party are sending videos by WhatsApp in which their own A.I. avatars deliver personal messages to specific voters about the government benefits they have received and ask for their vote.

Those video messages can be automatically generated in whichever of India’s dozens of languages the voter speaks. So can phone messages by A.I.-powered chatbots that call constituents in the voices of political leaders and seek their support.

Such outreach requires a fraction of the time and money spent on traditional campaigning, and it has the potential to become an essential instrument in elections. But as the technology races onto the political scene, there are few guardrails to prevent misuse.

Chatbots and personalized videos may seem more or less harmless. Experts worry, however, that voters will have an increasingly difficult time distinguishing between real and synthetic messages as the technology advances and spreads.

“It’ll be the Wild West and an unregulated A.I. space this year,” said Prateek Waghre, the executive director of the Internet Freedom Foundation, a digital rights group based in New Delhi. The technology, he added, is entering a media landscape already polluted with misinformation.

Around the world, elections have become a testing ground for the A.I. boom. The tools have been used to turn an Argentine presidential candidate into Indiana Jones and a Ghostbuster. During the New Hampshire primary, voters received robocall messages urging them not to vote, in a voice that was most likely artificially generated to sound like President Biden’s.

And in India, Mr. Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, or B.J.P., and the opposition Indian National Congress party have accused each other of spreading election-related deepfake content online.

One outpost on this new Indian frontier is in the western desert state of Rajasthan. On the ground floor of a residential building on a dusty back lane, a 31-year-old college dropout, Divyendra Singh Jadoun, operates an A.I. start-up, The Indian Deepfaker.

His team of nine people has been making commercials with A.I.-generated avatars of Bollywood actors and actresses. But earlier this year, political parties and politicians began asking him to do for them what he had done for celebrities. Of the 200 requests, Mr. Jadoun said, he took on 14.

Among those getting the A.I. treatment is Shakti Singh Rathore, a 33-year-old B.J.P. member. His job this election season is to tell as many people as possible about Mr. Modi’s programs and policies. So he decided to create a replica of himself.

“A.I. is wonderful and the way forward,” Mr. Rathore said as he settled in front of a video camera at the office of The Indian Deepfaker, preparing to become digitally incarnated. “How else could I reach the beneficiaries of Mr. Modi’s programs in such large numbers and in so short a period of time?”

As Mr. Rathore adjusted a saffron scarf with the party’s logo that hung around his neck, Mr. Jadoun instructed him, “Just look into the camera and talk as if the person is sitting right in front of you.”

With about five minutes’ worth of material, including an audio recording and profile shots, Mr. Jadoun went to work. He said he uses open-source A.I. systems and builds upon them with his own code.

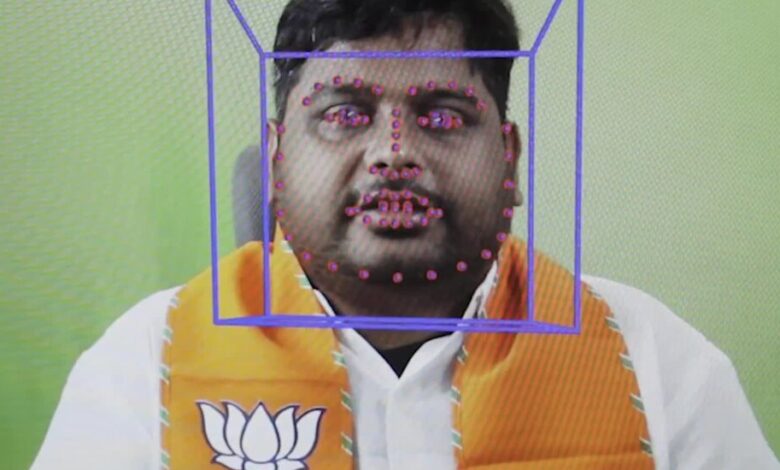

First, Mr. Rathore’s face was isolated from each frame of the recording.

Then data was collected from his facial features, including the size of his face and lips, as well as his gaze.

Mr. Jadoun said the data set was then fed into A.I. models that learn to predict facial patterns.

“You need to keep running it through the program and fine-tuning the face until you get the best face possible,” he said.

A “cloning algorithm” also analyzed the audio recording, learning the voice’s cadence and intonations. Mr. Jadoun said it often takes six to eight hours of tweaking to perfect the face and for the lips to sync with the words. The rest is largely automated.

In one demo, it took about four minutes to create around 20 personalized greeting videos.

Mr. Jadoun said his team could produce up to 10,000 videos a day. For larger jobs on deadline, it will rent graphics processing units.

Generative A.I. can also remove language barriers, which is especially helpful in a linguistically diverse country. Mr. Rathore’s avatar can be programmed to speak regional languages to reach the remotest corners of India.

Political parties are not only texting constituents video messages but also using cloned voices to call people directly, all powered by chatbots like ChatGPT.

In the past, when a party representative would call voters, they would hang up, Mr. Rathore said. “But now, when a local leader utters a voter’s name, it immediately catches their attention.”

During the conversation, the chatbot asks about local government programs that offer free electricity or funding for start-ups. Mr. Jadoun said the calls were recorded and transcribed for quality control and A.I. training.

Mr. Rathore said he had spent around $24,000 of his own money to reach about 1.2 million people through his video messages and phone calls and to receive information about who didn’t answer. He called it an investment in his future with the B.J.P.

Nikhil Pahwa, the editor of MediaNama, which covers digital media in India, said the personalized messages could be particularly powerful among Indians.

“India is a country where people love to take photos with celebrity impersonators,” he said. “So if they receive a call from, say, the prime minister, and he speaks as if he knows them, where they live and what their issues are, they would actually be thrilled about it.”

Mr. Waghre of the Internet Freedom Foundation questions whether A.I. content is persuasive enough to affect this year’s election. But he said the long-term effects could be problematic. “Once you normalize this in people’s information diet, what happens six months later when there are deceptive videos?” he said.

Mr. Modi himself has discussed adding disclaimers to A.I.-generated content so people are not being “misguided.” Mr. Jadoun and representatives of two other A.I. start-ups in India created what they call an “A.I. coalition manifesto,” pledging to protect data privacy and uphold election integrity. For instance, Indian Deepfaker videos are labeled “A.I. generated,” and its chatbots announce that they are A.I.-generated voices, Mr. Jadoun said.

Narendra Singh Bhati, 28, the owner of resorts in Rajasthan, received an A.I.-generated call from Mr. Rathore this week. Mr. Bhati said he was impressed with its personalization.

He said he had not realized that the call was A.I.-generated, although the script made that clear. “I even said goodbye to Mr. Rathore” at the end, Mr. Bhati said.