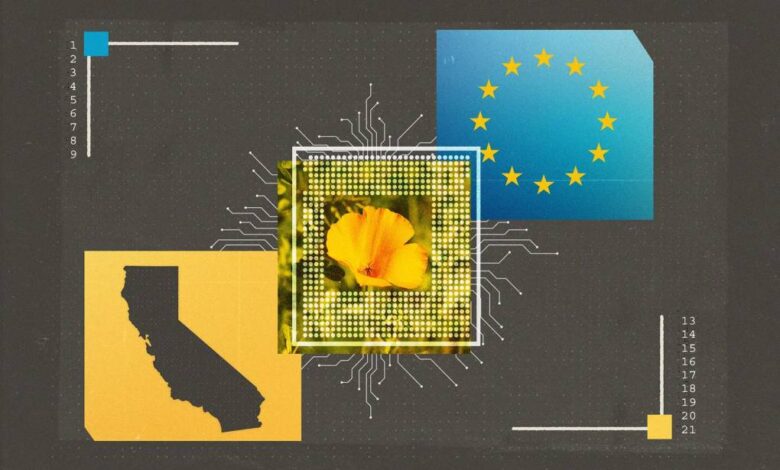

How California and the EU Work Together to Regulate Artificial Intelligence

Last month, de Graaf traveled to Sacramento to speak with several state lawmakers key to AI regulation:

The meeting to discuss the bills was at least the sixth trip de Graaf or other EU officials made to Sacramento in two months. EU officials who helped write the AI Act and EU Commission Vice President Josep Fontelles also made trips to Sacramento and Silicon Valley in recent weeks.

This week, EU leaders ended a years-long process with the passage of the AI Act, which regulates use of artificial intelligence in 27 nations. It bans emotion recognition at school and in the workplace, prohibits social credit scores such as the kind used in China to reward or punish certain kinds of behavior and some instances of predictive policing. The AI Act applies high risk labels for AI in health care, hiring, and issuing government benefits.

There are some notable differences between the EU law and what California lawmakers are considering. The AI Act addresses how law enforcement agencies can use AI, while Bauer-Kahan’s bill does not, and Wicks’ watermarking bill could end up stronger than AI Act requirements. But the California bills and the AI Act both take a risk-based approach to regulation, both advise continued testing and assessment of forms of AI deemed high risk, and both call for watermarking generative AI outputs.

“If you take these three bills together, you’re probably at 70%–80% of what we cover in the AI Act,” de Graaf said. “It’s a very solid relationship that we both benefit from.”

In the meeting, de Graaf said they discussed draft AI bills, AI bias and risk assessments, advanced AI models, the state of watermarking images and videos made by AI, and which issues to prioritize. The San Francisco office works under the authority of the EU delegation in Washington, D.C., to promote EU tech policy and strengthen cooperation with influential tech and policy figures in the United States.

Artificial intelligence can make predictions about people including what movies they want to watch on Netflix or the next words in a sentence, but without high standards and continuous testing, AI that makes critical decisions about people’s lives can automate discrimination. AI has a history of harming people of color, such as police use of face recognition, deciding whether to grant an apartment or home mortgage application. The technology has a demonstrated ability to adversely affect the lives of most people, including women, people with disabilities, the young, the old, and people who apply for government benefits.

In a recent interview with KQED, Umberg talked about the importance of striking a balance, insisting “We could get this wrong.” Too little regulation could lead to catastrophic consequences for society, and too much could “strangle the AI industry” that calls California home.

Coordination between California and EU officials attempts to combine regulatory initiatives in two uniquely influential markets.

The majority of the top AI companies are based in California, and according to startup tracker Crunchbase, for the past eight months, companies in the San Francisco Bay Area raised more AI investment money than the rest of the world combined.

The General Data Protection Regulation, better known as GDPR, is the European Union’s best known legislation for privacy protection. It also led to coinage of the term “the Brussels effect,” when enforcement of a single law leads to outsized influence in other countries. In this case, the EU law forced tech companies to adopt stricter user protections if they wanted access to the region’s 450 million residents. That law went into effect in 2018, the same year that California passed a similar law. More than a dozen U.S. states followed suit (PDF).

Defining AI

Coordination is necessary, de Graaf said, because technology is a global industry and it’s important to avoid policy that makes it complicated for businesses to comply with rules around the world.

One of the first steps to working together is a shared definition of how to define artificial intelligence so you agree on what technology is covered under a law. De Graaf said his office worked with Bauer-Kahan and Umberg on how to define AI “because if you have very different definitions to start with then convergence or harmonization is almost impossible.”

Given the recent passage of the AI Act, the absence of federal action, and the complexity of regulating AI, the Senate Judiciary staff lawyers held numerous meetings with EU officials and staff, Umberg told CalMatters in a statement. The definition of AI used by the California Senate Judiciary committee is informed by a number of voices including federal agencies, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the EU.

“I strongly believe that we can learn from each other’s work and responsibly regulate AI without harming innovation in this dynamic and quickly-changing environment” Umberg told CalMatters in a written statement.

The trio of bills discussed with de Graaf in April passed their respective houses this week. He suspects questions from California lawmakers will get more specific as bills move closer to adoption.

California lawmakers proposed more than 100 bills to regulate AI in the current legislative session.

“I think what is now the imperative for the Legislature is to whittle the bills down to a more manageable number,” he said. “I mean, there’s over 50 so that we focused particularly on the bills to these Assembly members or senators themselves.”

State agency also seeks to protect Californians’ privacy

Elected officials and their staff aren’t the only ones speaking with EU officials. The California Privacy Protection Agency — a state agency made to protect people’s privacy and require businesses comply with data deletion requests — also speaks regularly with EU officials, including de Graaf.