How is AI being used in Colorado classrooms?

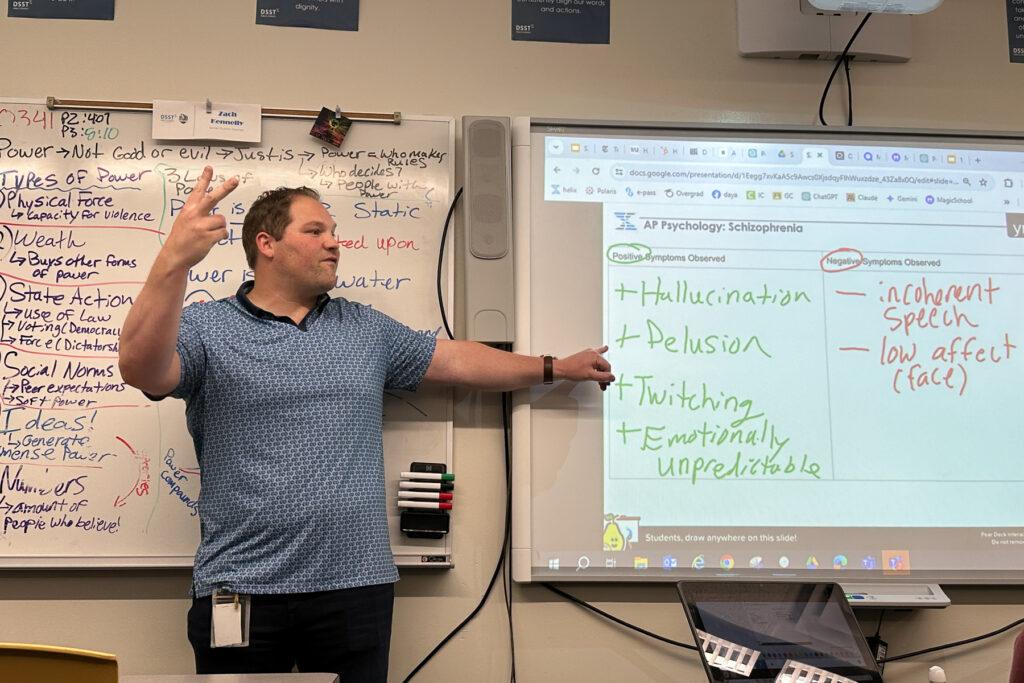

Scenes from “A Beautiful Mind” flicker on the screen in Zach Kennelly’s Advanced Placement Psychology class at DSST College View in southwest Denver.

The main character, economist and mathematician John Nash, is talking about his paranoid delusions. Every few minutes, Kennelly stops the film and students identify the symptoms of schizophrenia they’re seeing.

“Some delusions, the stress, his emotional unpredictability, the rage, and how he was seeing things other people weren’t seeing,” said one student.

“I’d agree,” said another. “Hallucinations and I saw weird movements in the mouth and body twitching. He has awareness over his own delusions.”

The film analysis is a creative but standard use of technology in a high school class.

Kennelly, however, is about to weave artificial intelligence into this lesson.

When you think of AI in the classroom, you might think of robotics and of kids coding programs using artificial intelligence. But today, Kennelly is two weeks into a pilot he created to introduce students to AI in typical classrooms.

Molly Cruse/CPR News

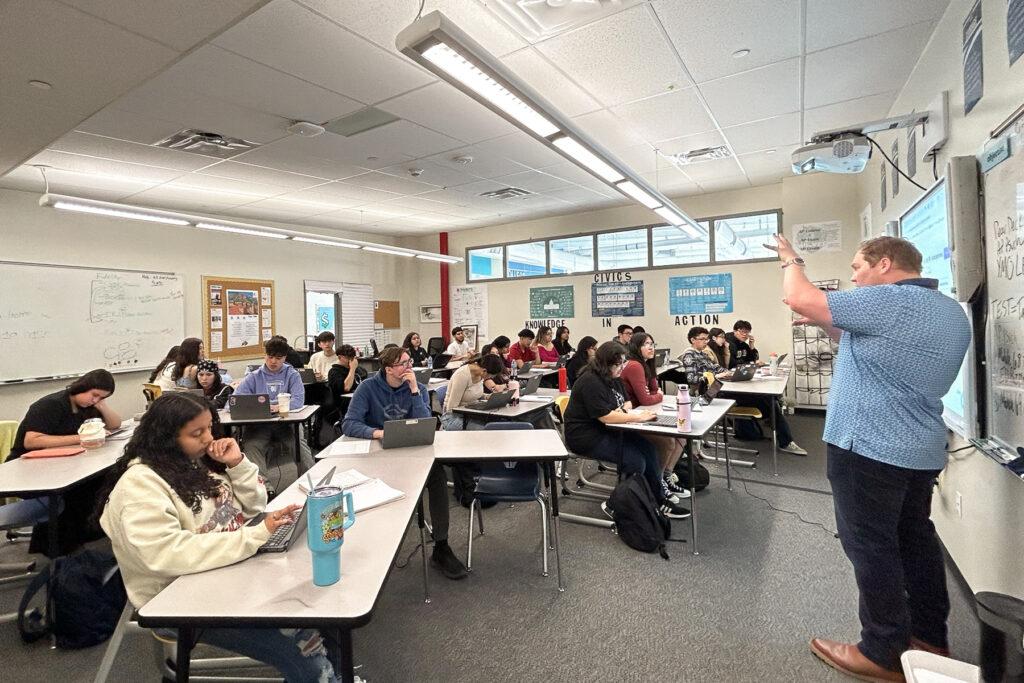

Kennelly, animated and enthusiastic, is on the cutting edge. A new RAND study shows that as of the fall of last year, just 18 percent of educators said they use AI for teaching. Most used it to adapt content to fit the level of their students and to generate instructional material.

Kennelly is going even further. He’s teaching his students about the immense power of artificial intelligence – both good and bad – and letting them use it in their work.

“The opportunity to explore, experiment, and learn alongside students, collaborating with AI, collaborating with students, them collaborating with me and across intelligences, if you will, has been really inspiring to me,” he said.

First, using artificial intelligence in AP Psychology

This week, the students have been studying schizophrenia. Before the film, Kennelly gave them a quiz he created using artificial intelligence, which he uses regularly to reduce his workload.

Next up? Students must write a paragraph stating a proposition about the symptoms of schizophrenia. They’ll use details from the film clips as evidence to support their analyses. They write their responses into a chatbot Kennelly has created using Magic School, a Colorado-based AI platform that lets teachers monitor students’ work as they use AI.

“We’re going to get some really awesome feedback from AI, and then you’re going to improve it,” Kennelly tells the class. “Again, the focus is we’re using AI to collaborate to make our work better — not do the work for us.”

Jenny Brundin/CPR News

Magic Student — from the same company that puts out Magic School — has a huge number of tools that students can use like:

- Build their own chatbots from scratch

- Create skits

- Do a rap battle between authors or famous figures in history

- Rewrite their own stories from the perspective of a character in a book

- Get tutoring

- Get help rewriting

- Talk to characters from plays

- Get help coding

- Translation

- Idea generation

- And a big one: get writing feedback.

Teachers have control over which tools to launch to students.

Kennelly, on his laptop, monitors each student as they collaborate with AI. Kennelly calls out to a student after she inputs her writing sample and gets feedback.

“Amber, what it gave you back is probably too lengthy of an example … Coach it up, tell it to give you a more concise example. Four to seven sentences, something along those lines so the feedback is really actionable for you,” he explains.

Kennelly used AI to provide the framework of sentences that students can use. They can choose “mild,” “medium” or “spicy” based on the difficulty level they want. He said those are especially helpful to the English language learners in this class.

Two weeks into the AI pilot, students are pretty impressed

Sophia, 17, found AI’s response to her writing helpful.

“I was reading it and saying, ‘This is what I lacked,’ so a lot of it was getting me the details of what I was missing like connecting back to scenes (from the film).”

Jenny Brundin/ CPR News

AI is giving something that school data shows they want most: more feedback, more quickly.

“It was like your built-in teacher giving you feedback on whatever you needed to, whatever you needed to work on, whether it was a new sentence or like, grammar, spelling, whatever … it gave it to you really quick,” said Brandon, a 17-year-old student.

Kennelly said students otherwise have to wait days sometimes to get feedback from him. Students typically would hand in an AI-improved version and their original.

They also like AI for brainstorming ideas. But ultimately, they think it will help them become better writers.

“It’s helped make my writing a lot more concise using words that I maybe haven’t used before, just expanding my vocabulary a lot,” said Rachel, a 17-year-old student.

Jenny Brundin/CPR News

The students seem to know intuitively that if they over-rely on AI to write, they won’t learn anything. Some educators may argue the struggle to fill a blank page is the way to learn.

But in this new world, could learning how to collaborate with AI be part of the learning journey? But what about if AI spits back feedback on your writing? Should you just blanket accept it? This is one of the most powerful tools in the world, so it’s gotta be right, no?

Amber disagrees.

“If AI told me, ‘Hey, you might want to change this,’ but I personally feel like it’s strong in my defense, I would keep it. So, AI doesn’t totally overpower everything,” she said.

But that’s something students need to be taught and that takes a certain confidence – something that Rachel feels is part of the learning process.

“Over time, you’re going to be able to develop the skills once you’ve seen how AI works.”

And what does the teacher think about the AI experiment so far?

Kennelly sees lots of potential — but also challenges that he’s looking forward to tackling.

One challenge will be helping students find their own authentic voice in their writing as they get assistance from AI. I ask if it could be squashing some of the student’s creativity. He said at this stage, he doesn’t know.

“And what I mean by that is I really do think only time we’ll be able to tell, and we as educators have such an important role in this because trying to ban AI or hide AI, it’s completely futile.”

Molly Cruse/CPR News

He knows AI in the classroom is still in the experimental phase. But the more teachers have the freedom to experiment, the more they can refine how this powerful tool should be used, he said. Right now, he’s sensing that using AI in targeted spots in classrooms is the right move. There are some classrooms where it probably shouldn’t be used as much. But there are other challenges.

Helping students understand what it means to collaborate with AI, peers and the teacher — that’s really a higher order of thinking than what students do now, which is to analyze their own work.

Then there’s privacy. Teaching students to not put any personally identifiable information into AI is key.

And another big AI learning curve Kennelly will tackle is in civics class.

Next up, using AI in civics class

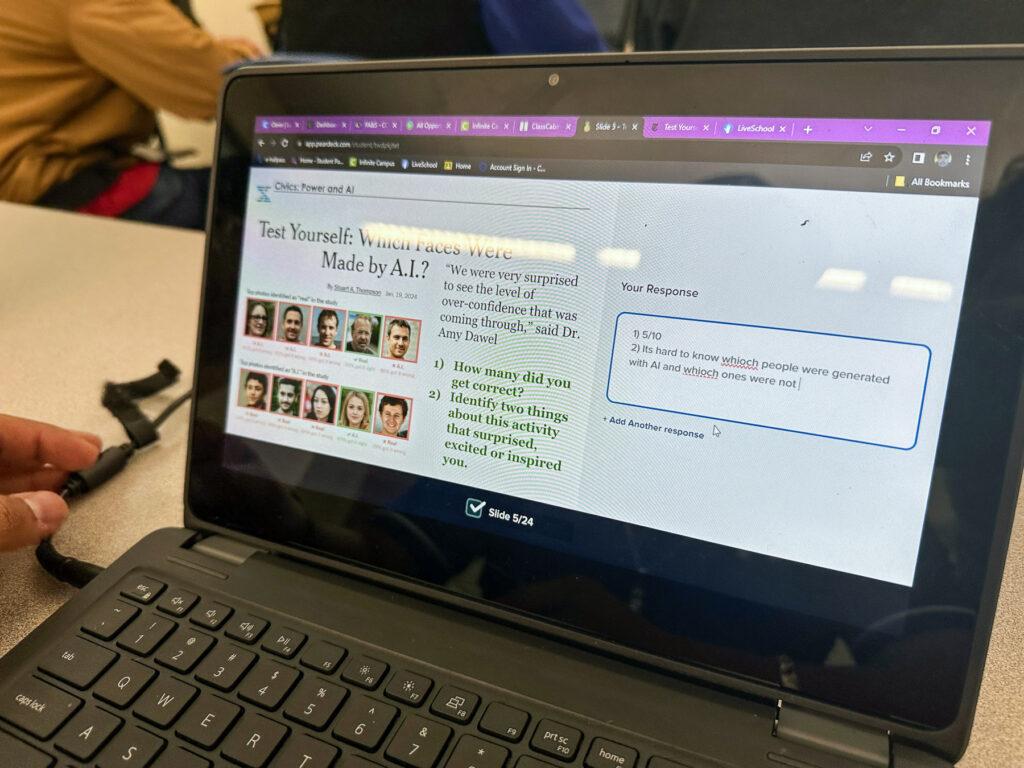

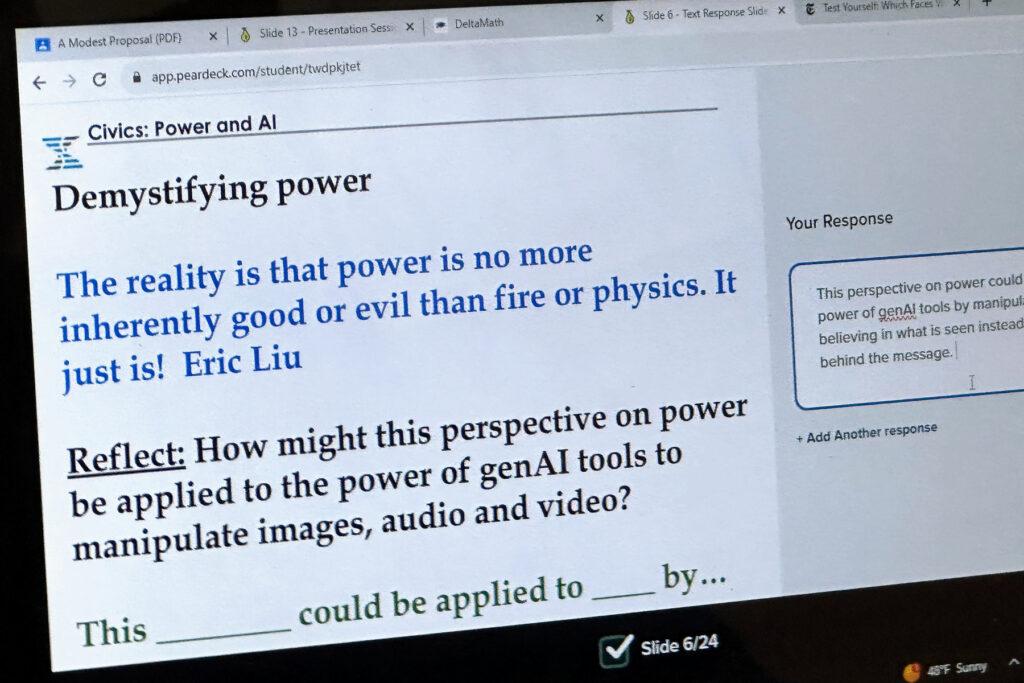

Kennelly’s next class of the day is civics. This class is studying power — who holds it, how AI is influencing it, and who is responsible for regulating it.

They start the lesson by studying AI-generated images and deep fakes, images, audio and video that are digitally altered often to spread false information. Then they take a New York Times quiz to see if they can tell which faces were made by AI. Most of the class is faked out the majority of the time. (One student does get 9 out of 10.)

Jenny Brundin/CPR News

“It made me trust pictures less … there’s some pictures where you think it’s real but it’s not,” Giovanni said.

“I feel the exact same way, right?” Kennelly said. “I am questioning so much especially about social media and news … has this been vetted? Has this been analyzed for some level of deep fake? What are some of the key things that I need to be on the lookout for that clearly can effectively mislead me?”

The class examines a graph based on a national survey of where people stand on who should regulate AI: industry, government or a combination. One student notices that of the people who use AI, most believe there should be some kind of government regulation.

That squares with what Estrella, a senior, thinks about AI regulation.

“If the government is not there to put laws (in place) to protect us and our personal stuff, it’s going to take over,” she said.

The class watches a video on deep fakes, and examines a case study by deep-fake detector Reality Defender — a campaign where Chinese actors used deep fakes to sow conflict and confusion and possibly alter a Taiwanese election.

The civics students first foray into learning about the overwhelming power of AI is … well, overwhelming

“I knew about AI but I didn’t think much about it,” Estrella said. “But after learning about it, it just blows your mind … it’s just really big and they’re ways to use it that are good and ways it can be bad.”

She said it’s crucial to learn about it in high school. The class has made Jayla more skeptical of taking what she hears from political candidates at face value.

“Who you’re voting for could actually not be their true selves … and who you really want as a president.”

Jenny Brundin/CPR News

But Kennelly’s goal in this civics class is a positive one. Ultimately the students will collaborate with each other and use generative AI tools to write a letter to one of their elected representatives about a challenge they want to address.

The class has already studied the ways that predictive AI impacts their life, including their ability to get a mortgage, to potentially be wrongfully flagged as having committed fraud, and to make it harder to complete the federal financial aid form (FAFSA).

“Helping students realize they have power, they know how to use their power, and they can use AI to scale their power to address some of the inequities that they see in their world,” Kennelly said.