Hurricane season in Atlantic to be ‘extraordinary’

Mark Poynting,Climate reporter

NOAA/Getty Images

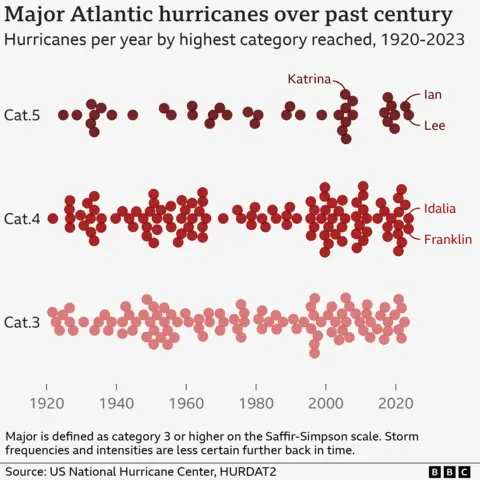

NOAA/Getty ImagesThe North Atlantic could get as many as seven major hurricanes of category three strength or over this year, which would be more than double the usual number, the US weather agency NOAA has warned.

Normally you’d expect three major hurricanes in a season.

As many as 13 Atlantic hurricanes of category one or above are forecast for the period, which runs from June to November.

Record high sea surface temperatures are partly to blame, as is a likely shift in regional weather patterns.

While there’s no evidence climate change is producing more hurricanes, it is making the most powerful ones more likely, and bringing heavier rainfall.

“This [hurricane] season is looking to be an extraordinary one,” NOAA administrator Rick Spinrad said in a news conference.

The recent weakening of the El Niño weather pattern – and the likely switch to La Niña conditions later in the year – creates more favourable atmospheric conditions for these storms in the Atlantic.

In contrast to the Atlantic, NOAA had already predicted a “below-normal” hurricane season in the central Pacific region, where a move to La Niña has the opposite effect.

On average, the Atlantic basin – which includes the Atlantic Ocean, Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico – experiences 14 named tropical storms a year, of which seven are hurricanes and three are major hurricanes.

Tropical storms become hurricanes when they reach peak sustained wind speeds of 74mph (119km/h). ‘Major’ hurricanes (category three and above) are those reaching at least 111mph (178km/h).

In total NOAA expects between 17 and 25 named tropical storms, of which between eight and 13 could become hurricanes and between four and seven could become major ones.

The highest number of major hurricanes in a single Atlantic season is seven, seen in both 2005 and 2020. NOAA’s forecast suggests that 2024 could come close to that.

The exact causes of individual storms are complex, but two key factors are behind the forecast.

Firstly, there is the likely switch from El Niño to La Niña within the coming months, which helps these storms to grow more easily.

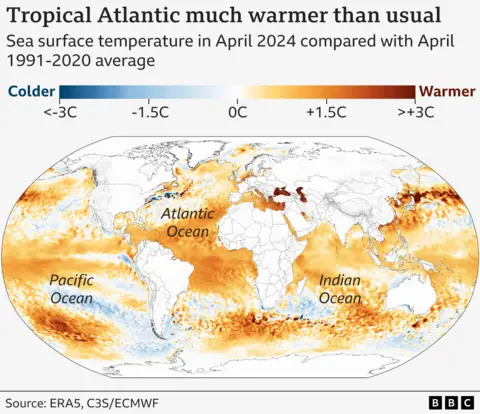

And secondly, sea surface temperatures are much warmer than usual in the main hurricane development region in the tropical Atlantic.

That often means more powerful hurricanes, because warmer waters provide more energy for storms to grow as they track westwards.

“All the ingredients are in place” for an intense hurricane season, said Ken Graham, director of the US National Weather Service.

To draw attention to the way that global warming is making the highest intensity storms more likely, a recent study explored the possibility of creating a new category six level.

This “would alert the public that the strongest tropical cyclones that we are now experiencing are unprecedented and the reason for that [is] the warming of the surface oceans because of climate change,” explains study lead author Michael Wehner, senior scientist at Berkeley Earth.

Hurricane categories only take into account wind speeds. But these storms pose other major hazards, such as rainfall and coastal flooding, which are generally worsening with climate change, NOAA warned.

Warmer air can hold more moisture, increasing the intensity of rainfall.

Meanwhile, storm surges – the short-term increases to sea level from hurricanes – are now happening on top of a higher base. That is because sea levels are now higher, principally due to melting glaciers and warmer seas.

“Sea-level rise increases the total flood depth, making today’s hurricanes more damaging than prior year’s storms,” says Andrew Dessler, a professor of atmospheric science at Texas A&M University.

Given the active forecast, researchers stress the need for the public to be aware of the hazards these storms can pose – in particular “rapid intensification events”, where hurricane wind speeds increase very quickly, and so can be especially dangerous.

“We are already seeing overall increases to the fastest rates at which Atlantic hurricanes intensify – which means that we are likely already seeing an increased risk of hazards for our coastal communities,” explains Andra Garner, an assistant professor at Rowan University in the US.

“It can still be difficult to forecast rapid intensification of storms, which in turn escalates the challenges that arise when trying to protect our coastal communities.”

Graphics by Erwan Rivault and Muskeen Liddar