Implementing integrated solutions at scale

4.2 Action area II: Implementing integrated solutions at scale

The international community has promoted sound and sustainable natural resources management and restoration, including specific approaches for land, soil and water and ecosystem services. These approaches can help define critical thresholds in natural resource systems, leading to beneficial outcomes when wrapped up as packages or programmes of technical, institutional, governance and financial support.

4.2.1 Planning land and water resources – a crucial first step

Sustainable resources management across all agroclimatic zones is a crucial first step. As pressures on land and water systems risk compromising agricultural productivity where growth is most needed, land and water resources planning at different decision-making levels will play a key role in promoting sustainable and efficient resource use.

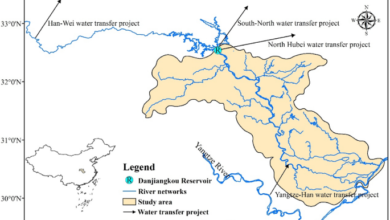

A wide range of resource planning tools and approaches support decision makers, planners and practitioners, working at global, national and local levels, to plan, take actions and scale out SLM options (Box S.4). Although lack of data often constrains effective planning, resources planners respond to the challenge and use remote sensing, big data and innovative analytical methods that revolutionize planning. Models are increasingly used in participatory approaches involving all stakeholders. They are used to develop and adapt food and agricultural systems to improve economic and social conditions and generate multiple benefits and opportunities for local and national economies and private/public investments.

©FAO/Jim Morgan

Box S.4 Integrated catchment planning and governance for SLM scaling out

The Transboundary Agroecosystem Management Project in the Kagera River basin was one of the 36 projects of the TerrAfrica Strategic Investment Programme for SLM in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Kagera River basin (Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and United Republic of Tanzania) supports the farming, herding and fishing livelihoods of over 16 million people. Yet, rapid population growth, intensification of agriculture, progressive reduction in farm sizes, and unsustainable land and water management practices have degraded the resource base.

Catchment planning and management approaches were integrated into local governance strategies to promote participatory and sustainable land, water and biodiversity management. In Burundi and the United Republic of Tanzania, watershed management groups were established to prioritize and oversee implementation, resulting in improvements in food security and resolution of resource conflicts. In Uganda and the United Republic of Tanzania, participatory land-use planning enabled communities and the government to endorse the results of catchment planning and integrated agroecosystem management for achieving agricultural productivity, natural resources, climate, biodiversity, food security and livelihood benefits.

©FAO/Giulio Napolitano

Source: FAO, 2017.

©FAO/Simon Maina

New tools are helping resources planners to understand the extent and location of yield and production gaps, as many regions continue to suffer poor rainfed crop yields and production shortfalls. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, yields are only 24 percent of what is achievable with higher levels of input and sound resources management. Substantial yield gaps also occur in Central America, India and the Russian Federation, attributed to low inputs and ineffective management. Effective planning enables decision makers to target interventions and enhance food production according to needs and investment opportunities.

The land resources planning toolbox developed by FAO offers a resource that supports participatory land resources planning. It provides information and an inventory of tools and approaches to help stakeholders working in different regions and sectors and at different levels. It is web based, freely available and updated regularly with summary descriptions and links to a comprehensive range of land resources planning tools and approaches developed by FAO and other institutions.

FAO water resources tools include water accounting and auditing, water harvesting, modular farming systems, non-conventional water resources planning, a drought toolbox including early warning systems, AquaCrop, the environmental flow tool and an integrated fisheries system to increase benefits and sustainability by integrating fisheries with irrigation schemes.

Land and water management also needs to be an integral part of disaster risk management plans, flood and drought management plans, national adaptation plans and plans to meet NDCs developed under the Paris Agreement.

4.2.2 Packaging workable solutions

The private sector’s diverse spectrum, from small-scale farmers through to those involved in processing, storing, transporting and marketing phases of the food value chain, including their suppliers, offers a significant opportunity to respond to land and water challenges. Their choice of technology and site selection for operations, environmental stewardship and social responsibility practices are under a spotlight, and offer more initiatives and best-practice examples, including certification and corporate disclosure schemes.

FAO adopted sustainable intensification and CSA to help Members adapt to future increases in demand for calories and to limited land and water resources. Sustainable intensification includes increasing resource-use efficiency and optimizing external inputs, minimizing adverse environmental impacts of food production, closing yield gaps on underperforming existing agricultural lands, and using improved crop varieties and livestock breeds. Climate-smart agriculture aims to increase agricultural productivity and incomes, adapt and build resilience to climate change, and reduce GHG emissions.

©FAO/Benedicte Kurzen/NOOR

©FAO/Believe Nyakudjara

The World water development report 2018 focuses on NbSs for water. These solutions can be a powerful strategy for encouraging the agricultural sector to redirect investment in ecosystem services. They offer long-term and cost-effective interventions to address water management, soil restoration, biodiversity and conservation.

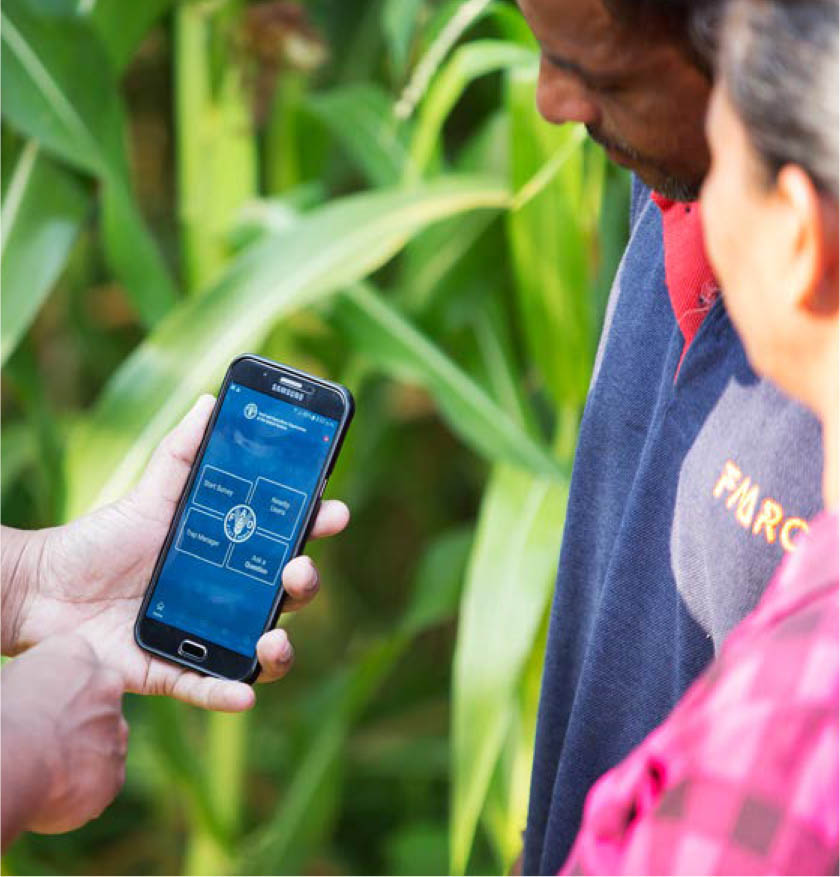

Integrated land and water management approaches are now supercharged with information and communications technology (ICT) and products. Even the simple introduction of mobile phones will provide the coordination backbone for multidisciplinary and multi-stakeholder land management and will remove many barriers to scaling out (Box S.5). Climate-smart programmes can now push sophisticated environmental or pest control content to users in the field.

Box S.5 Advances in ICT help smallholder rice farmers to exploit crop diversification

Advances in ICT, remote sensing and big data can push targeted policies and strategies cost-effectively. Knowledge and mobile phone applications to support farmers and herders improve productivity, manage associated environmental risks, and ensure sustainable land and water management are available. An example includes identifying rice fallows in Asia in real time. This provides opportunities to exploit fallows for crop diversification, such as growing food legumes, applying nutrients to address soil and plant deficiencies, and minimizing agrochemicals, and also for climate forecasting.

Source: Biradar et al., 2020.

©FAO/Hoang Dinh Nam

Treating land and soils with care and managing water responsibly can be emphasized through knowledge-based approaches, particularly when targeted through landscape or environmental services approaches.

Agriculture’s “solution space” has expanded. Advances in agricultural research have broadened the technical palette for land and water management. Nature-based solutions can be combined with pest control, crop phenology and soil biodiversity, and applied at scale to reduce the build-up of environmental pressures.

Increasing land and water productivity is crucial for achieving food security, sustainable production and SDG targets. However, there is no “one size fits all” solution. A “full package” of workable solutions is now available to enhance food production and tackle the main threats from land degradation, increasing water scarcity and declining water quality. But these will succeed only when there is a conducive enabling environment, strong political will, sound policies and inclusive governance, and full participatory planning processes across all sectors and landscapes.

Measures to adapt to and mitigate the impacts of climate change in agriculture are part of a continuum ranging from addressing the drivers of vulnerability to explicitly targeting climate change impacts.

©Pixabay/Sasint

4.2.3 Avoiding and reversing land degradation

Human-induced land degradation is now a priority, although it has been largely ignored in the past. It is avoidable and reversible in many instances. Approaches such as SLM that address soil degradation challenges and manage soil moisture, plant growth and associated and biodiversity will be crucial in meeting global food security aspirations and SDGs. These will need mainstreaming and scaling out with support from effective policies and financial mechanisms. Studies suggest that restoration costs less than a third of the cost of inaction, and preventing degradation is generally far less costly than restoration.

©FAO/Benedicte Kurzen/NOOR

Land degradation neutrality, a state where land area and quality support ecosystem function and enhance food security, can help governments face the challenges of degradation and set targets and plan interventions based on the principle of Avoid > Reduce > Reverse land degradation.

The World Overview of Conservation Approaches and Technologies (WOCAT) is a knowledge system to inform SLM and LDN implementation. The WOCAT system includes techniques and approaches that include water harvesting, soil and water conservation, rainfed and irrigated agriculture, livestock and agropastoral management, watershed management, and climate adaptation and mitigation.

©FAO/Lekha Edirisinghe