Is AI Being Built For The Manager Class Alone?

I know this is a weird question to bring up this far into the computer revolution, but: Who are computers for?

Is the target audience for the average computer a jet-setting executive or sales person, trying to figure out how to keep the machine running? Is it the high-flying creative or developer, hoping to reach new levels of expression or productivity? Is it the office drone or startup jockey? Or is it the nebulous end user, constantly in consumption mode, looking for new ways to enjoy their favorite TikTok video or Wikipedia page?

It’s a trick question, of course: The target audience is all of them. It’s a broad product with myriad use cases!

But it seems like tech companies are not aware of this, based on the AI-driven products they’ve been recently showing off or describing to users far and wide.

Recently in an interview with Nilay Patel’s Decoder podcast, Zoom founder and CEO Eric Yuan was asked the direction he saw meetings going in, and he was asked about AI’s role in meetings. This is what he came up with:

Essentially, in order to listen to the call but also to interact with a participant in a meaningful way. Let’s say the team is waiting for the CEO to make a decision or maybe some meaningful conversation, my digital twin really can represent me and also can be part of the decision making process. We’re not there yet, but that’s a reason why there’s limitations in today’s LLMs. Everyone shares the same LLM. It doesn’t make any sense. I should have my own LLM—Eric’s LLM, Nilay’s LLM. All of us, we will have our own LLM. Essentially, that’s the foundation for the digital twin. Then I can count on my digital twin. Sometimes I want to join, so I join. If I do not want to join, I can send a digital twin to join. That’s the future.

Essentially, he is describing a future in which he is handing off some managerial duties to AI bots, so he can be in five meetings at once, with the idea that it will supercharge his productivity and ensure that teams will continue to be able to function even though he is not able to be on every single call.

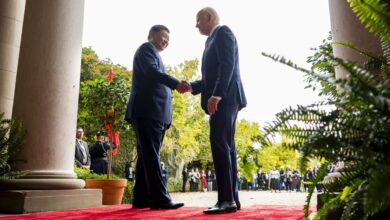

Who asked for this? (via Microsoft)

As weird as this sounds, it is clearly cut from the same cloth as a similar idea just added to Windows called Recall. The tool is designed to give you a photographic memory by tracking literally everything you’ve done on your PC, which sounds like a feature that someone who is quadruple-booked in lots of meetings would love to have access to, as it would allow them to remember a lot of information. The problem is, most people who use Windows are not, in fact, CEOs, and they do not need this level of memory in their machines, and the result has been called out as something of a “privacy nightmare.”

SEO guru Jon Henshaw, who recently took a role at CNET (where hopefully he can fix some of this mess) recently posted a quote on Mastodon that I absolutely love. It’s from author Joanna Maciejewska, who nailed down a sentiment that really describes exactly what we’re seeing right now:

I want AI to do my laundry and dishes so that I can do art and writing, not for AI to do my art and writing so that I can do my laundry and dishes.

Essentially, the people making AI software have decided that AI should clear the slates of everything else to help make management problems easier at the cost of the stuff that many people don’t think AI should be used for, like creative work.

The problem is, managers only make up a small percentage of the employees that use software. There are people who use computers to make things, and if the computer did the job for you, it would be a huge loss from a creativity standpoint, because you weren’t able to flex your muscles at all.

Executives, meanwhile, have a different mindset—they want to execute at a high level, and if technology gets them there, awesome. But the AI we’re seeing created only seems to care about the latter example, and it makes sense once you consider who signs massive software contracts. That’s right: managers and executives.

Ed Zitron identified the problem that led to this aptly in a 2021 Atlantic piece titled “Say Goodbye to Your Manager,” noting a Harvard Business Review piece from five years earlier that put the percentage of managers at what he described as “an alarming statistic that shows how bloated America’s management ranks had become.” His take is basically the same one I have; we force good employees into management roles unnecessarily:

Right now, we basically have only one track (management), and it actively drains talent from an organization by siloing and repressing it in supervisory roles. Employees may rise into management, then leave to go make more money managing somewhere else. What we need—and will likely see—are more organizations opening a different track for people who are very good at their specific job, where these people are compensated for being great at what they do and mentoring others. While not everybody is a born teacher or mentor, I’ve yet to see someone very good at their job who doesn’t have anything useful to impart to the younger generation. Countless companies let high-flying performers write books and do seminars about their successes, but rarely take that success and look inward to see how it might be given to others. And instead of vacuous perks such as pool tables and free lunches, perhaps we simply give talent the means to get distractions and annoyances out of the way, such as assistants and software that automates parts of their job.

Zitron, whose excellent newsletter Where’s Your Ed At is the perfect level of cynicism for the current economy, was right at the time. And he probably still is. But there’s a problem—in the past few years, the management class has come roaring back in a big way, using tools like back-to-office mandates to reassert their role in the ecosystem. And AI, rather than helping to solve the problems of over-management, seems intent on solving the surface-level problems of managers and the executive class, while ignoring the fact that their high-level performers are getting bogged down by those very things.

Think about it. “This writer seems to have a hard time hitting deadlines!” That’s OK, we’ll replace him with a bot, so you can meet your business goals and don’t have to rejigger your team. “I don’t want to hire a freelancer to make this poster!” Perfect, we’ll figure out a way to make something that is almost as good as the poster they would have made!

And it goes on and on. Now, we’re starting to see tools that literally seem focused on trying to make managers remember more things, or take on an omnipresent role. It is not long before your quote-unquote “boss” is in every one of your Zoom meetings, looking over your shoulder and ensuring that you’re meeting a given quota and limiting small talk.

The pitch of this is that, if we get rid of all of these busywork tasks, we’ll eventually be opened up just enough for higher-level tasks. Which, great! But that just assumes that all of us want to be managers.

I think about how there’s this assumption in journalism that every reporter secretly wants to be an editor, and how the incentive structures are built around this fact. But the truth is, sometimes reporters just want to report.

Mitch Hedberg’s best joke, in my estimation, points at this tension:

I got into comedy to do comedy, which is weird, I know. But when you’re in Hollywood and you’re a comedian, everyone wants you to do other things besides comedy. Say, “Alright, you’re a stand-up comedian, can you act? Can you write? Write us a script.” They want me to do things that’s related to comedy but not comedy. That’s not fair. So if I was a cook and I worked my ass off to become a good cook, they said, “Alright, you’re a good cook. Can you farm?”

Not everyone wants to be a manager or an executive, and that’s fine. Sometimes, people just really like making things.

But the problem is, the people making and marketing the AI are executives or managers, and they’re seeing the problem as executives or managers. The people buying the software? They’re also executives or managers, which means the incentives are built around their needs, not the needs of the broader organization.

Once I was at a job where a piece of enterprise software was brought in to manage complex projects, and it was hyped up for weeks internally. But by the time it actually ended up in the hands of the end-user, it was clear that it was a complex, jumbled mess, and it was gone in six months, despite the fact that a presumably huge contract was put in to set up this software.

Can you guess who decided to bring it in? It probably wasn’t a rank-and-file worker.

Compare this to how tools like Slack entered the workplace. IT teams initially hated tools like Slack because they were added by actual workers outside the chain of command. But Slack eventually won out over the mandated tools with the insane overhead, because it actually matched how people worked.

Right now, we’re at the stage of AI software where it’s being pushed from on high, which means it’s being sold to executives that may or may not fully understand how the technology is going to work for their teams. That’s a recipe for disaster, and leads to ideas like embedded OS spying and digital twins in meetings. If AI is going to work, it needs to come from the bottom-up, like Slack, or AI is going to be useless for the vast majority of people in the workplace.

With the new generation of AI software, we keep asking our cooks to farm, instead of enabling them to be the best cooks they can be. By the time we’re done, nobody will remember the recipe anymore.