It’s Not Just Russia: China Joins the G7’s List of Adversaries

President Biden was eager to get off the stage at the Group of 7 summit Thursday night, clearly a bit testy after answering questions about Hunter Biden’s conviction and the prospects of a cease-fire in Gaza.

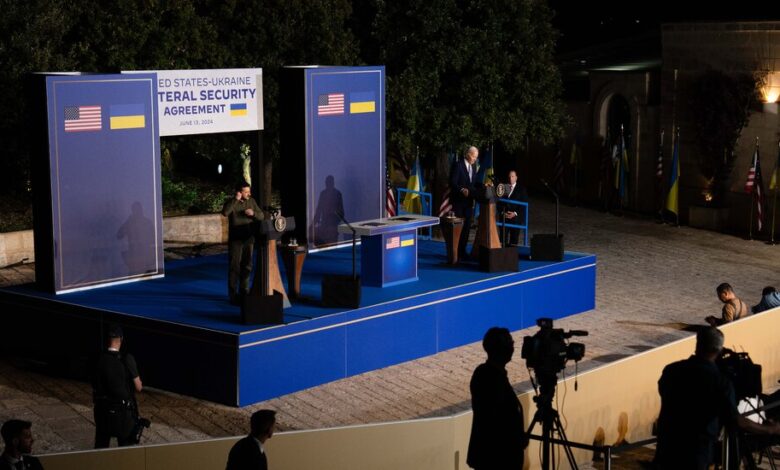

But at the end of his news conference with President Volodymyr Zelensky of Ukraine, he couldn’t seem to help jumping in as the Ukrainian leader spoke delicately about China’s tightening relationship with Russia. He leaned into his microphone as soon as Mr. Zelensky was finished.

“By the way, China is not supplying weapons” for the war in Ukraine, Mr. Biden said, “but the ability to produce those weapons and the technology available to do it.”

“So, it is, in fact, helping Russia,” he said.

Throughout the Group of 7 summit meeting in Puglia, China has been the lurking presence: as the savior of “Russia’s war machine,” in the words of the summit’s final communiqué; as an intensifying threat in the South China Sea; and as a wayward economic actor, dumping electric cars in Western markets and threatening to withhold critical minerals needed by high-tech industries.

In total, there are 28 references to China in the final communiqué, almost all of them describing Beijing as a malign force.

The contrast with China’s portrayal just a few years ago is sharp.

At past summits, the West’s biggest economies talked often about teaming with Beijing to fight climate change, counterterrorism and nuclear proliferation. While China was never invited into the G7 the way Russia once was — Moscow joined the group in 1997 and was suspended when it annexed Crimea in 2014 — Beijing was often described as a “partner,” a supplier and, above all, a superb customer of everything from German cars to French couture.

No longer. This year, China and Russia were frequently discussed in the same breath, and in the same menacing terms, perhaps the natural outcome of their deepening partnership.

A senior Biden administration official who sat in on the conversations of the leaders gathered at the summit, and later briefed reporters, described a discussion of China’s role that seemed to assume the relationship would be increasingly confrontational.

“As time goes on, it becomes clear that President Xi’s objective is for Chinese dominance,” ranging from trade to influencing security issues around the world, the official told reporters, declining to be named as he described the closed-door talks.

But it was China’s support of Russia that constituted a new element at this year’s summit, and perhaps changed minds in Europe. The subject of China’s role was barely raised in the last two summits, and when it was, it was often about the influence of its top leader, Xi Jinping, as a moderating force on President Vladimir V. Putin, especially when there were fears that Mr. Putin might detonate a nuclear weapon on Ukrainian territory.

This time, the tone was very different, starting in the communiqué itself.

“We will continue taking measures against actors in China and third countries that materially support Russia’s war machine,” the leaders’ statement said, “including financial institutions, consistent with our legal systems, and other entities in China that facilitate Russia’s acquisition of items for its defense industrial base.”

The United States had insisted on including that language and was pressing its allies to match Mr. Biden’s action earlier this week, when the Treasury Department issued a number of new sanctions devised to interrupt the growing technological links between Russia and China. But so far, few of the other G7 nations have made similar moves.

Inside the Biden administration, there is a growing belief that Mr. Xi’s view of China’s role in the Ukraine war has changed in the past year, and that it will throw its support increasingly behind Mr. Putin, with whom it has declared a “partnership without limits.”

Even just a few months ago, most administration officials viewed that line as hyperbole, and even Mr. Biden, in public comments, expressed doubts that the two countries could overcome their huge suspicions of each other to work together.

That view has now changed, and some administration officials said they believe that Beijing was also working to discourage countries from participating in a peace conference organized by Mr. Zelensky. More than 90 countries will be at the conference in Switzerland this weekend, but Russia will not participate — and China, which a year ago expressed interest in a variety of cease-fire and peace plans, has said it will not attend either.

In the view of Alexander Gabuev, the director of the Carnegie Russia Eurasia Center in Berlin, China is now opposing any peace efforts in which it cannot be the central player.

“Xi, it seems, will not abandon his troublesome Russian partner or even pay lip service to aiding Kyiv,” Mr. Gabuev wrote in Foreign Affairs on Friday. “Instead, China has chosen a more ambitious, but also risker, approach. It will continue to help Moscow and sabotage Western-led peace proposals. It hopes to then swoop in and use its leverage over Russia to bring both parties to the table in an attempt to broker a lasting agreement.”

American officials at the summit said they largely agreed with Mr. Gabuev’s diagnosis, but said they doubted China had the diplomatic experience to make it work.

But the change in views about China reached far beyond the questions swirling around an endgame in Ukraine. European countries that had worried a few years ago that the United States was being too confrontational with China, this year signed on to the communiqué, with its calls for more robust Western-based supply chains that were less reliant on Chinese companies.

By implication, the jointly issued communiqué also accused China of a series of major hacks into American and European critical infrastructure, urging China “to uphold its commitment to act responsibly in cyberspace” and promising to “continue our efforts to disrupt and deter persistent, malicious cyberactivity stemming from China, which threatens our citizens’ safety and privacy, undermines innovation and puts our critical infrastructure at risk.”

That infrastructure reference appeared to be tied to a Chinese program that the United States calls “Volt Typhoon.” American intelligence officials have described it as a sophisticated effort by China to place Chinese-created malware in the water systems, electric grids and port operations of the United States and its allies.

In congressional testimony and interviews, Biden administration officials have charged that the malware’s real purpose is to gain the capability to shut down vital services in the United States in the midst of a Taiwan crisis, slowing an American military response and setting off chaos among Americans who would be more concerned about getting the water turned back on than keeping Taiwan independent.