Live Updates: Search Continues for 6 Missing in Baltimore Bridge Collapse

The Baltimore bridge disaster on Tuesday upended operations at one of the nation’s busiest ports, with disruptions likely to be felt for weeks by companies shipping goods in and out of the country — and possibly by consumers as well.

The upheaval will be especially notable for auto makers and coal producers for whom Baltimore has become one of the most vital shipping destinations in the United States.

As officials began to investigate why a nearly 1,000-foot cargo ship ran into the Francis Scott Key Bridge in the middle of the night, companies that transport goods to suppliers and stores scrambled to get trucks to the other East Coast ports receiving goods diverted from Baltimore. Ships sat idle elsewhere, unsure where and when to dock.

“It’s going to cause a lot of chaos,” said Paul Brashier, vice president for drayage and intermodal at ITS Logistics.

Sources: Maryland Port Administration, OpenStreetMap, MarineTraffic

Note: Ship positions are as of 2:46 p.m. Eastern time.

The New York Times

The closure of the Port of Baltimore is the latest hit to global supply chains, which have been strained by monthslong crises at the Panama Canal, which has had to slash traffic because of low water levels; and the Suez Canal, which shipping companies are avoiding because of attacks by the Houthis on vessels in the Red Sea.

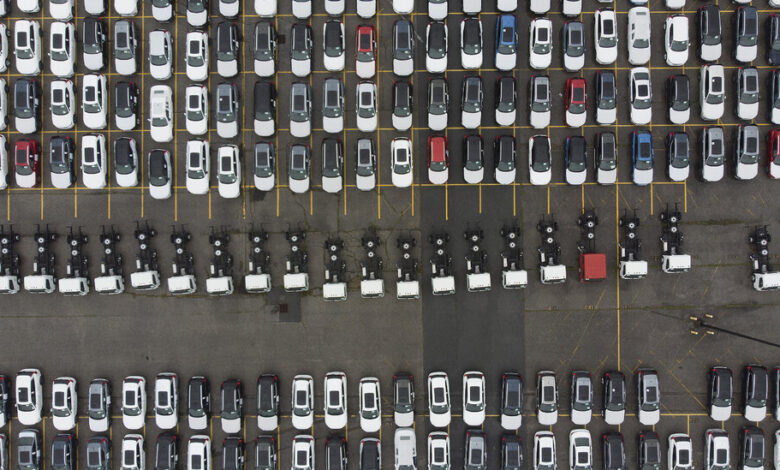

The auto industry now faces new supply headaches.

Last year, 570,000 vehicles were imported through Baltimore, according to Sina Golara, an assistant professor of supply chain management at Georgia State University. “That’s a huge amount,” he said, equivalent to nearly a quarter of the current inventory of new cars in the United States.

The Baltimore port handled a record amount of foreign cargo last year, and it was the 17th biggest port in the nation overall in 2021, ranked by total tons, according to Bureau of Transportation Statistics.

Baltimore ranks first in the United States for the volume of automobiles and light trucks it handles, and for vessels that carry wheeled cargo, including farm and construction machinery, according to a statement by Gov. Wes Moore of Maryland last month.

The incident is another stark reminder of the vulnerability of the supply chains that transport consumer products and commodities around the world.

The extent of the disruption depends on how long it takes to reopen shipping channels into the port of Baltimore. Experts estimate it could take several weeks.

Baltimore is not a leading port for container ships, and other ports can likely absorb traffic that was headed to Baltimore, industry officials said.

Stephen Edwards, the chief executive of the Port of Virginia, said it was expecting a vessel on Tuesday that was previously bound for Baltimore, and that others would soon follow. “Between New York and Virginia, we have sufficient capacity to handle all this cargo,” Mr. Edwards said, referring to container ships.

“Shipping companies are very agile,” said Jean-Paul Rodrigue, a professor in the department of maritime business administration at Texas A&M University-Galveston. “In two to three days, it will be rerouted.”

But other types of cargo could remain snarled.

Alexis Ellender, a global analyst at Kpler, a commodities analytics firm, said he expected the port closure to cause significant disruption of U.S. exports of coal. Last year, about 23 million metric tons of coal exports were shipped from the port of Baltimore, about a quarter of all seaborne U.S. coal shipments. About 12 vessel had been expected to leave the port of Baltimore in the next week or so carrying coal, according to Kpler.

He noted that it would not make a huge dent on the global market, but he added that “the impact is significant for the U.S. in terms of loss of export capacity.”

“You may see coal cargoes coming from the mines being rerouted to other ports instead,” he said, with a port in Norfolk, Va., the most likely.

If auto imports are reduced by Baltimore’s closure, inventories could run low, particularly for models that are in high demand.

“We are initiating discussions with our various transportation providers on contingency plans to ensure an uninterrupted flow of vehicles to our customers and will continue to carefully monitor this situation,” Stellantis, which owns Chrysler, Dodge, Jeep and Ram, said in a statement.

Other ports have the capacity to import cars, but there may not be enough car transporters at those ports to handle the new traffic.

“You have to make sure the capacity exists all the way in the supply chain — all the way to the dealership,” said Mr. Golara, the Georgia State professor.

A looming battle is insurance payouts, once legal liability is determined. The size of the payout from the insurer is likely to be significant and will depend on factors including the value of the bridge, the scale of loss of life compensation owed to families of people who died, the damage to the vessel and disruption to the port.

The ship’s insurer, Britannia P&I Club, part of a global group of insurers, said in a statement that it was “working closely with the ship manager and relevant authorities to establish the facts and to help ensure that this situation is dealt with quickly and professionally.”

The port has also increasingly catered to large container ships like the Dali, the 948-foot-long cargo vessel carrying goods for the shipping giant Maersk that hit a pillar of the bridge around 1:30 a.m. on Tuesday. The Dali had spent two days in Baltimore’s port before setting off toward the 1.6-mile Francis Scott Key Bridge.

State-owned terminals, managed by the Maryland Port Administration, and privately owned terminals in Baltimore transported a record 52.3 million tons of foreign cargo in 2023, worth $80 billion.

Materials transported in large volumes through the city’s port include coal, coffee and sugar. It was the ninth-busiest port in the nation last year for receiving foreign cargo, in terms of volume and value.

The bridge’s collapse will also disrupt cruises traveling in and out of Baltimore. Norwegian Cruise Line last year began a new fall and winter schedule calling at the Port of Baltimore.

March 26, 2024

:

An earlier version of this article misstated the Port of Baltimore’s rank among U.S. ports. It was the nation’s 17th biggest port by total tons in 2021, not the 20th largest.

How we handle corrections