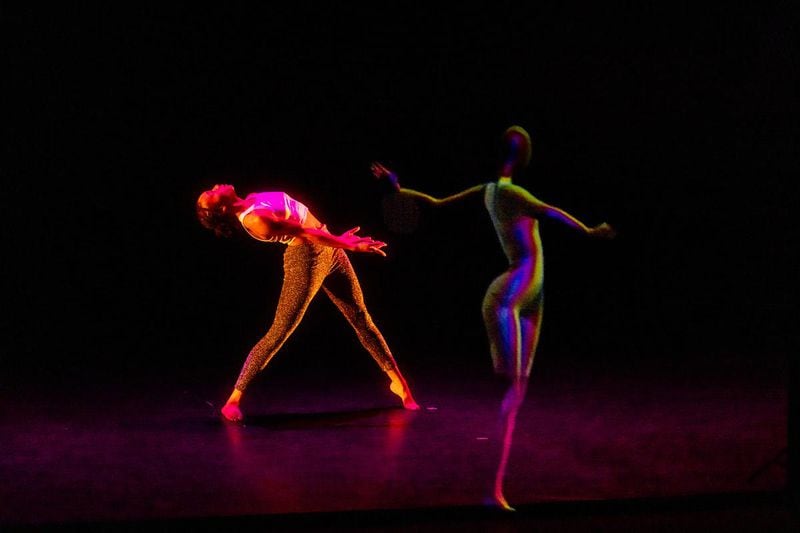

LuminAI puts human dancers and artificial intelligence on the same stage

Most of the Georgia Tech scientific team had never been onstage in a theater before and said they were profoundly moved by the experience. Nevertheless, LuminAI — and its projected avatar — literally and figuratively loomed large over a well-produced student showing combined with a proof-of-concept demonstration of the technology.

Credit: Matthew Yung | Kennesaw State University

Credit: Matthew Yung | Kennesaw State University

LuminAI is a project of the Expressive Machinery Lab at Georgia Tech, headed by Brian Magerko, professor of digital media and director of graduate studies in digital media. As he explained in the after-show talkback, LuminAI comprises two main components: 1) a computer “agent” that processes information it receives about a human partner’s movement from a motion capture device, and 2) a projected avatar that the agent controls and uses to respond to its partner through improvised movement of its own.

Dance and computers are having a moment in studios, theaters, labs, think tanks and lecture halls worldwide. Of course, the history of human-computer interaction in dance goes back decades. Last year, Dance Magazine profiled several artists who are making dance with AI and following in the footsteps of Merce Cunningham, who used computers in his choreography in the late 1980s.

The article also highlighted ethical and intellectual property concerns raised by how AI is being trained in a new wave of projects designed to teach computer agents about human motion and gestural expression.

Some dancers, for example, have helped engineers solve problems such as getting a smart-home device to respond properly to a user’s gestural commands or develop algorithms to coordinate the movements of a Boston Dynamics robot “dog.”

Other dancer-scientists and movement analysts such as Amy LaViers and Catherine Maguire, co-authors of “Making Meaning With Machines” (MIT Press), engage in fundamental research related to understanding how humans assign meaning to movement in order to create better, more accessible robots or human-computer interfaces.

Credit: Photo by Robin Wharton

Credit: Photo by Robin Wharton

LuminAI reaches a turning point

Up to this point, LuminAI — currently led by Magerko and Andrea Knowlton, associate professor of dance at KSU — leaned towards fundamental research. This performance, however, seemed to mark a potential turning point in the 12-year endeavor, one where the primary focus on building a technology that works accurately and consistently might begin a shift toward developing applications for particular contexts.

Knowlton joined the project three years ago, but Magerko has been studying human-machine collaboration for more than a decade. In 2016, he debuted an early version of LuminAI with T. Lang Dance in a special performance of choreography from “Post,” the final installment of Lang’s “Post Up” series.

Though Knowlton is a relative newcomer to the project, she and Magerko described themselves and their respective institutions as full partners in the current LuminAI research. “It’s refreshing to be in a space where dance is taken seriously,” Knowlton told ArtsATL in an interview. “Dancers hold a huge repository of embodied knowledge, dating back to the beginning of civilization, and for that reason, we are poised to make valuable contributions to AI and digital embodiment.”

Knowlton and student dancers from her improvisation class at KSU have “trained” LuminAI to recognize human movement and, via its projected avatar, respond in kind. All told, they have contributed some 5,000 individual movements to LuminAI’s database through direct motion capture. They’ve also generated and annotated hours of video, which have been used to “teach” LuminAI about dance improvisation and the non-verbal cues humans use to communicate while collaborating.

Research participants who are not in Knowlton’s class are compensated for their time, and students in the class may opt out if they choose. Strict protocols established by an institutional review board, a body that oversees university and government-funded research involving human subjects, protect participant data.

Regarding how the collaboration has influenced her work as an artist and enhanced students’ learning, Knowlton said their engagement with the project has helped make the often implicit and occasionally mysterious processes around collaborative improvisation more explicit. “Using this technology, students break things down by watching themselves practicing their art. They have to explain what they’re doing at a given moment. All of that has improved their awareness of how dancers, and artists in general, move their practice forward through collaboration,” Knowlton said.

For example, Knowlton described how, even though dancers cite eye contact as being very important in their collaborative improvisation, they think they are making more eye contact than they are. “The moments are significant but brief,” she said. “Just as important are the minute changes in facial expression and breath that communicate play.”

Magerko, too, highlighted how much insight LuminAI researchers have gained into human behavior. “We have learned so much about how humans make things together. That alone would have been a productive outcome,” he told ArtsATL.

The end goal has always been, though, to create an AI that responds to human gesture and engages with human collaborators in creative activity. Friday’s performance was LuminAI’s chance to demonstrate what it learned in Knowlton’s class.

Credit: Matthew Yung | Kennesaw State University

Credit: Matthew Yung | Kennesaw State University

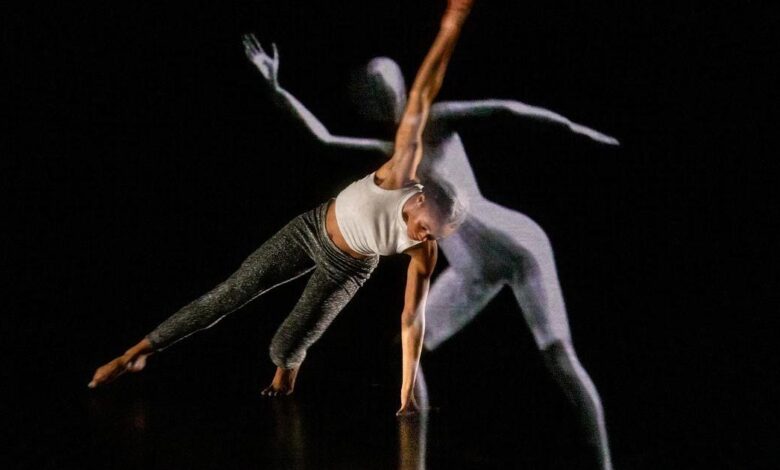

LuminAI on stage

Before the curtain came up, projection screens at the sides of the theater played short film clips and photo slideshows of LuminAI’s avatar moving on a desktop screen and dancers improvising together in the studio while wearing motion capture suits or partnering with the avatar. During the performance, sound designer Paul Stevens stood at stage right and improvised an electronic score using looping, mixing and a keyboard. He also worked settings that control LuminAI’s appearance, making it grow or shrink, multiply or break apart for a moment into pixelated streams of color.

The dancers, LuminAI’s peer tutors from Knowlton’s class, stood behind and sometimes in front of a mostly transparent scrim. Spotlights demarcated places at each side of the stage where a single dancer would be within range of the Microsoft Kinect devices the team used to capture and transmit the dancer’s movements to LuminAI’s processor.

LuminAI’s avatar looked like a vaguely feminine layman — one of those small wooden mannequins used for figure drawing — and was projected onto the scrim.

LuminAI’s relatively conventional form, Knowlton said, came out of a design process that began with the average measurements of all KSU dancers, which were taken by the program’s costume designers over the years. It also involved numerous rounds of feedback from the student participants in her class.

The program alternated between dance improvisation and screening segments of a short documentary Knowlton produced about the project.

LuminAI first appeared on stage as a shadowy overlay, hovering in front of one dancer as she moved in the spotlight at stage right.

At first, the avatar mimicked her movements. Later, as the projection appeared at different scales and places in relation to the human ensemble, LuminAI’s interactions evolved from mimicry into amplification of or contrast with the movements of its human partners, depending on what phase of engagement it determined their interaction had entered.

Following the performance, Knowlton and the Georgia Tech research team took their seats in chairs onstage for the talkback. The dancers joined them a few minutes later, sitting on the stage floor in front of the others.

LuminAI’s performance was cool but uneven. Its motions were recognizable but nowhere near as fluid and technically clear as a human dancer’s. It seemed to glitch, occasionally shifting position as if it had been flipped front to back by the flick of a giant invisible finger. LuminAI looked plausibly humanoid when still and even when mimicking a partner, but its original movements were stilted and sometimes very alien.

Part of the problem, Magerko explained to ArtsATL, is that during the performance, LuminAI accurately recognized the ebb and flow of a collaborative engagement and predicted the appropriate gestural response only about 20% of the time. That low score is connected to an issue with the team’s data collection, one they solved during preparations for the performance. “With another two days in studio with the dancers, we can get that number up to 80%,” said Magerko.

The other challenge stems from using the Kinect for motion capture. During the question and answer session, Magerko said the fancy suits provide higher fidelity data but have an unfortunate tendency to catch fire. So the researchers settled on continuing with the Kinect, which Magerko has been using since very early on.

Once LuminAI can more accurately parse gestural input, the team can experiment with more sophisticated motion capture technology.

Better inputs will presumably lead to better outputs in future performances. Magerko said an educational museum exhibit about LuminAI will be traveling to the Museum of Science and Industry in Chicago at the end of May. This summer, the exhibit will pop up at the Museum of Design Atlanta as part of MODA’s Sunday Funday series.

ArtsATL asked both researchers what happens when LuminAI achieves an accuracy rate of 80% or higher and its gestural responses become more coordinated and realistic. They acknowledged the potential for military and security applications. Magerko gave another example: “One of my colleagues suggested LuminAI could be used to identify suspected pickpockets in a crowd.”

The researchers themselves, however, are interested in LuminAI’s capacity to boost human potential. Knowlton described how LuminAI might facilitate physical therapy during recovery after an injury or surgery. Magerko said Milka Trajkova, a dancer and lead research scientist on the Georgia Tech side, envisions LuminAI as an assistive technology in dance training, helping dancers optimize their technique for both artistry and injury prevention.

One option would be releasing the technology under an open source license, making it freely available to the public. “After all, this research has been funded by taxpayer dollars,” Magerko said.

He and Knowlton both had to stop and think for a moment when asked what part the dancers would play in deciding LuminAI’s commercial future. They agreed, however, the artists should have a seat at the table when that decision is made.

::

Robin Wharton studied dance at the School of American Ballet and the Pacific Northwest Ballet School. As an undergraduate at Tulane University in New Orleans, she was a member of the Newcomb Dance Company. In addition to a bachelor of arts in English from Tulane, Robin holds a law degree and a Ph.D. in English, both from the University of Georgia.

Credit: ArtsATL

Credit: ArtsATL

MEET OUR PARTNER

ArtsATL (artsatl.org) is a nonprofit organization that plays a critical role in educating and informing audiences about metro Atlanta’s arts and culture. ArtsATL, founded in 2009, helps build a sustainable arts community contributing to the economic and cultural health of the city.

If you have any questions about this partnership or others, please contact Senior Manager of Partnerships Nicole Williams at nicole.williams@ajc.com.