Megacasting Is One More Way Tesla Just Has to Be Different

From the May/June issue of Car and Driver.

While much of the automotive industry continues to build electric vehicles at a loss, Tesla is making them at a profit. The now Texas-based company achieved this through a variety of measures, such as selling its carbon credits to automakers whose product lines fall short of federal mandates. But Tesla has also introduced new manufacturing methods that cut down on assembly costs.

This includes a technology called megacasting—or gigacasting in Tesla parlance—developed by Italy’s Idra Group. Tesla uses it at a number of its factories, including the Texas facility that produces the Model Y and the Cybertruck.

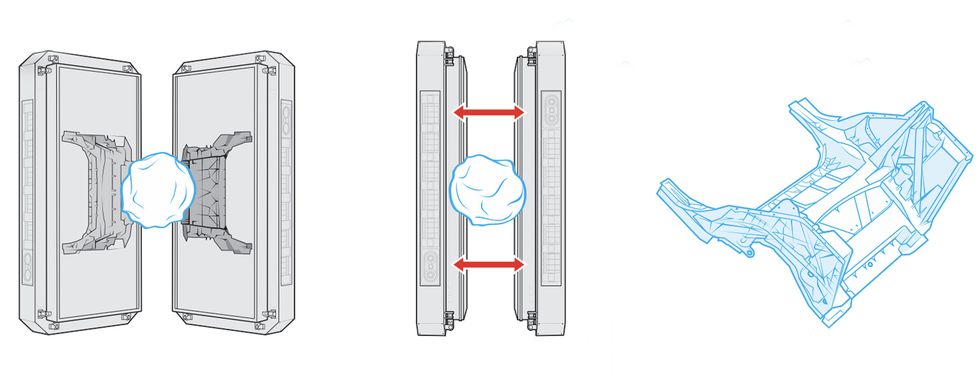

Megacasting is a form of die-casting, a process that involves jamming liquid metal (typically aluminum, in the automotive industry’s case) into a mold under high pressure. The amount of pressure depends on the size of a given component. A piece with a larger surface area needs more metal injected into the mold at higher pressure, necessitating an increase in the clamping force of the press used to hold the model together during the casting procedure.

Traditionally, automakers use dozens of different extruded, stamped, forged, and cast pieces in the structures of their models, bonding, welding, and sticking these pieces together as part of the assembly process. Megacasting, however, eliminates this assembly complexity, replacing a multitude of parts with one large piece, such as an entire front or rear structure. Whereas smaller parts stamped and cast under conventional methods may need a few hundred tons of clamping force, the additional metal and larger surface area of parts produced using megacasting requires a press capable of achieving upward of 9000 tons of force.

These so-called “megapresses” are expensive machines, but the efficiency of this casting process lowers the manufacturing cost of an individual car. And that’s why Tesla isn’t the only automaker investing in this technology.

“One megacasting replaces 70 to 100 parts,” says a Volvo Cars spokesperson. “This means that all activities connected to producing, shipping, and assembling these parts are removed.”

Megacasting doesn’t just cut production costs; it can also create parts that are lighter than the equivalent assembled cast or stamped pieces. This combination is a boon to manufacturers of battery-electric vehicles looking for ways to decrease mass while increasing EV models’ profit margins, driving range, and performance.

“With less plant floor space required, less equipment, and faster vehicle production rates, the integration of body-structure components is becoming an essential strategy for manufacturers,” says Edwin Pope, principal analyst at S&P Global Mobility.

The implementation of this manufacturing process in the auto industry is still in its nascent stage. Toyota, for instance, is developing a megacasting system that aims to improve production flexibility by dividing molds into two camps: general-purpose molds used in a number of vehicles, which stay mounted in the megacasting machinery, and interchangeable specialized molds specific to given models. Toyota claims it can swap the latter in as little as 20 minutes, a feat anticipated to deliver a 20 percent boost in productivity.

Still, there are perils to megacasting. Though casting a single structural piece mitigates the risk of potential human or robot error during the assembly of a multipiece component, it also means there’s limited leeway for error. Automakers that use traditional methods to create a vehicle structure can quickly and inexpensively address an individual part or assembly issue while salvaging any unaffected material. However, a significant flaw in a megacast structure could require scrapping the entire piece.

This concern extends to repair costs as well. “Castings have very limited capacity to deform [in a collision]; they’re going to fracture,” says Sam Abuelsamid, Guidehouse Insights principal research analyst. “When that happens, [the casting] becomes irreparable.”

For cars with megacast structures, this means that even a relatively minor impact can have substantial implications. “Instead of replacing a small component, you’re replacing an entire structure,” Abuelsamid says. “So it’s not that it can’t be repaired, but that the cost is so high the vehicle will more often end up getting totaled.”

Tim Stevens is a freelance automotive and technology journalist with more than 25 years of experience. Tim frequently contributes to major domestic and international online, print, and broadcast news outlets, sharing his insights and perspectives on everything from cybersecurity to supercars. Based in upstate New York, when not writing about or working on cars he can often be found rebuilding pinball machines or getting lost in the woods.