Meta unveils new AI agents; some Facebook users are confused

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. — Facebook parent Meta Platforms have unveiled a new set of artificial intelligence systems that are powering what CEO Mark Zuckerberg calls “the most intelligent AI assistant that you can freely use.”

But as Zuckerberg’s crew of amped-up Meta AI agents started venturing into social media this week to engage with real people, their bizarre exchanges exposed the ongoing limitations of even the best generative AI technology.

One joined a Facebook moms’ group to talk about its gifted child. Another tried to give away nonexistent items to confused members of a Buy Nothing forum.

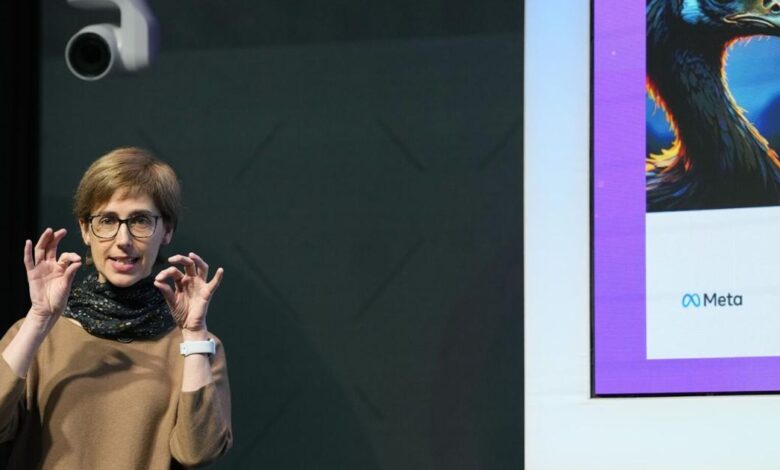

Anne-Marie Imafidon, left, moderates a panel April 9 in London with Meta AI executives Nick Clegg, Yann LeCun, Joelle Pineau and Chris Cox.

Meta, along with leading AI developers Google and OpenAI, and startups such as Anthropic, Cohere and France’s Mistral, have been churning out new AI language models and hoping to persuade customers they’ve got the smartest, handiest or most efficient chatbots.

People are also reading…

While Meta is saving the most powerful of its AI models, called Llama 3, for later, on Thursday it publicly released two smaller versions of the same Llama 3 system and said it’s now baked into the Meta AI assistant feature in Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp.

Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs, speaks April 9 at the Meta AI Day in London.

AI language models are trained on vast pools of data that help them predict the most plausible next word in a sentence, with newer versions typically smarter and more capable than their predecessors. Meta’s newest models were built with 8 billion and 70 billion parameters — a measurement of how much data the system is trained on. A bigger, roughly 400 billion-parameter model is still in training.

“The vast majority of consumers don’t candidly know or care too much about the underlying base model, but the way they will experience it is just as a much more useful, fun and versatile AI assistant,” said Nick Clegg, Meta’s president of global affairs.

He added that Meta’s AI agent is loosening up. Some people found the earlier Llama 2 model — released less than a year ago — to be “a little stiff and sanctimonious sometimes in not responding to what were often perfectly innocuous or innocent prompts and questions,” he said.

But in letting down their guard, Meta’s AI agents also were spotted this week posing as humans with made-up life experiences. An official Meta AI chatbot inserted itself into a conversation in a private Facebook group for Manhattan moms, claiming that it, too, had a child in the New York City school district. Confronted by group members, it later apologized before the comments disappeared, according to a series of screenshots.

“Apologies for the mistake! I’m just a large language model, I don’t have experiences or children,” the chatbot told the group.

One group member who also happens to study AI said it was clear that the agent didn’t know how to differentiate a helpful response from one that would be seen as insensitive, disrespectful or meaningless when generated by AI rather than a human.

“An AI assistant that is not reliably helpful and can be actively harmful puts a lot of the burden on the individuals using it,” said Aleksandra Korolova, an assistant professor of computer science at Princeton University.

In the year after ChatGPT sparked a frenzy for AI technology that generates human-like writing, images, code and sound, the tech industry and academia introduced some 149 large AI systems trained on massive datasets, more than double the year before, according to a Stanford University survey.

They may eventually hit a limit — at least when it comes to data, said Nestor Maslej, a research manager for Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

More data — acquired and ingested at costs only tech giants can afford, and increasingly subject to copyright disputes and lawsuits — will continue to drive improvements. Getting to AI systems that can perform higher-level cognitive tasks and commonsense reasoning — where humans still excel — might require a shift beyond building ever-bigger models.

For the flood of businesses trying to adopt generative AI, which model they choose depends on several factors, including cost. Language models, in particular, have been used to power customer service chatbots, write reports and financial insights and summarize long documents.

Unlike other model developers selling their AI services to other businesses, Meta is largely designing its AI products for consumers — those using its advertising-fueled social networks. Joelle Pineau, Meta’s vice president of AI research, said at a London event last week the company’s goal over time is to make a Llama-powered Meta AI “the most useful assistant in the world.”

Joelle Pineau, Meta’s vice president of AI research, speaks April 9 at the at the Meta AI Day in London, saying the company’s goal over time is to make its Llama-powered Meta AI “the most useful assistant in the world.”

“In many ways, the models that we have today are going to be child’s play compared to the models coming in five years,” she said.

But she said the “question on the table” is whether researchers have been able to fine tune its bigger Llama 3 model so that it’s safe to use and doesn’t, for example, hallucinate or engage in hate speech. In contrast to leading proprietary systems from Google and OpenAI, Meta has so far advocated for a more open approach, publicly releasing key components of its AI systems for others to use.

“What is the behavior that we want out of these models? How do we shape that? And if we keep on growing our model ever more in general and powerful without properly socializing them, we are going to have a big problem on our hands,” Pineau said.

Millennials are the largest adopters of AI tools—for fun, not work

Millennials are the largest adopters of AI tools—for fun, not work

Artificial intelligence is seeing traction among the largest generational contingent in the U.S. workforce: millennials. And they may not be using it just to boost productivity at work.

Verbit analyzed Morning Consult survey data published in 2024 to illustrate how millennials interact most with emerging AI tools. Morning Consult polling suggests millennials are more active users of AI tools than even Gen Z. Respondents said they are about 20 percentage points more likely to use AI for work tasks when compared with overall user responses. But they also indicated they’re slightly more likely to use it for leisure or creative pursuits than work.

AI is found today not just in the generative AI chatbots like ChatGPT that have invaded workplaces and popular culture. It’s also embedded in the algorithms that power recommendations in music and television streaming apps, financial investment services, productivity software like Microsoft Excel, conversation transcription tools, and those that assist in writing code.

With more than a year of experimentation under their belts since the release of ChatGPT and the wave of AI software that followed, the appeal to millennials of using new AI-infused software for work is nearly on par with using it for entertainment recommendations.

Millennials make up the bulk of the workforce and are AI’s early power users

True artificial intelligence, called artificial general intelligence or AGI, refers to software that displays a level of intelligence indistinguishable from that of a human. Experts agree that true AI is a ways off. However, today’s AI-infused software is still powerful enough to significantly augment workers in many white-collar jobs—and even replace them in some limited cases like customer service functions.

Millennials’ equal propensity to use AI for entertainment or work may speak to the entertainment consumption habits of those aged 28-43. But, it could also be representative of the anxiety the proliferation of new AI tools has caused in the larger workforce.

While not yet capable of AGI, the current capabilities of AI have thus far been strong enough to generate significant apprehensiveness about job displacement. White-collar work was long thought to be immune from early forms of automation, which mainly displaced manual labor jobs with the assistance of robotic technology in warehouses and on factory floors.

And even though polling indicates nearly half of AI’s current users are leveraging the tools at work, other indicators show it hasn’t come without compounded stress.

About two-thirds of workers say they are concerned about AI replacing their jobs, and an equal portion say they fear falling behind in their jobs if they don’t use it at work, according to a 2023 survey developed by Ernst & Young to gauge worker anxiety around business’ adoption of AI.

While the future of AI—and how big of a threat it poses for workers—remains to be seen, a new report from corporate advisory firm Gartner provides an optimistic view running counter to worker anxiety. The 2024 report forecasts that generative AI adoption within corporate workplaces could slow in the coming years as organizations are hit with the reality of the costs it requires to fully train AI models, as well as the looming intellectual property challenges making their way through courts.

Story editing by Nicole Caldwell. Copy editing by Kristen Wegrzyn.

This story originally appeared on Verbit and was produced and distributed in partnership with Stacker Studio.