New Magnetic Playdough for Squishier Robots

If I asked you to picture a robot, what would you imagine? Perhaps a Star Wars droid, a robotic arm in a factory or one of those new, artificially smiling robot waiters. What you might not picture is a magnetic, moldable putty driven around by a magnetic field. This is a new material described in a paper from September 2023 in the Journal Advanced Materials, created for the next generation of robots: smaller, repairable, maneuverable designs.

The material consists of tiny magnets embedded within the putty, says Meng Li, one of the paper’s authors. But these aren’t ordinary magnets. They stay pointing in the same direction, even if they are placed in a magnetic field. This is unlike weaker magnets which can be affected by an external field and will spin around to reorient themselves.

When testing the material, Li says, “every day I found new phenomena.” The putty can be easily shaped and then re-molded, with endless opportunities for reuse. It’s cheap, scalable and easy for other labs to create. And if it breaks apart, it can heal itself if the two segments are reconnected, making it useful for adaptable designs that might need to break and reform (think how putty will stick back to itself). These properties make it an ideal material for prototyping: when engineers make models of their product to test it before manufacturing.

Its ability to heal also opens the material up to being used in robots that need to adapt over time, like robots that need to go through a tight space and reconstruct themselves on the other side. “It’s amazing because you can have robots that are damaged and repair themselves,” says Cecilia Laschi, a professor of biorobotics at the University of Singapore.

So how does the putty actually function as a robot? In the paper, Li introduces four experiments demonstrating the use of the new material. In the first experiment, the putty is used to create a magnetic field that has an adjustable strength, which can be used for testing magnets. In the second experiment, putty was attached to non-magnetic materials to make them act as magnets. Li foresees how this could be used for retrieving materials from inaccessible locations. In the third experiment, a long string of the putty is exposed to a magnetic field and grows like a vine, wrapping itself around a pole.

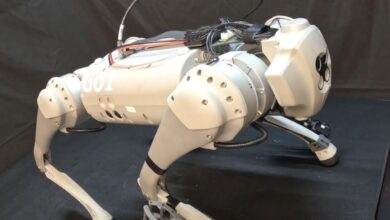

In the fourth experiment, the team created an entire robot made only of the putty. Its arms, legs and body were magnetized in different ways, so that when it was put in a magnetic field it crawled along without any computer on board. “It was very easy to make,” Li says.

Because the magnets inside the putty won’t flip themselves to align with an external field, the putty can also be used to improve the safety of medical catheters that currently use ordinary magnets to stay in place. According to Li, it can be difficult to know the orientation of the catheter’s magnet in your body: “If you want it to move to the left but the polarity has changed, it might move to the right instead.” But with this putty, the orientation of the magnet wouldn’t matter. Doctors would then be able to move the catheter inside a body more precisely.

Of course, there are applications Li admits she probably hasn’t thought of yet. “I’m excited to see how people respond to this new material,” she says. “This paper is just a proof of concept, what’s next is up to the community.”