New Tech Gives Artists A Fighting Chance In The Battle Against Generative AI

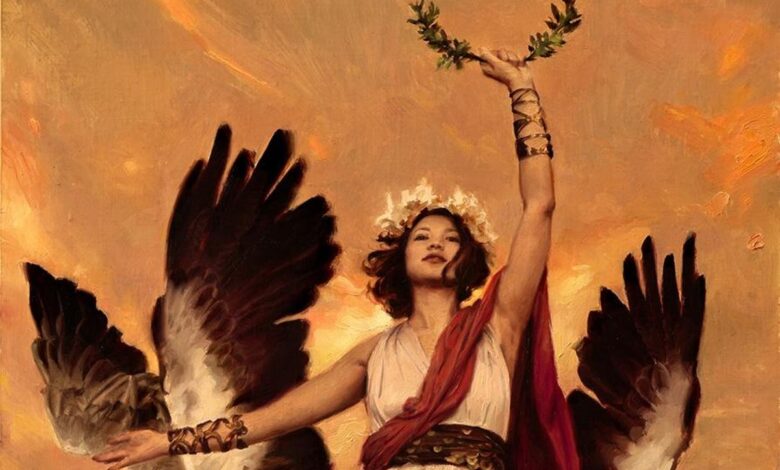

“Musa Victoria,” an original artwork by Karla Ortiz, was the first public application of Glaze, … [+]

When generative AI art tools like Dall-E, Stable Diffusion and Midjourney first appeared in 2022, they dazzled users by producing complex images in a variety of artistic and photographic styles from simple text prompts. But the novelty of the technology soon gave way to questions and concerns. How would we deal with a flood of synthetic imagery that was difficult or impossible to distinguish from reality? How would these tools disrupt the economics of the media, entertainment, advertising, publishing and commercial art industries? And what are the legal and ethical implications of building generative AI systems using data “scraped” from the Internet, including work under copyright, without consent or compensation?

Over the past two years, these concerns and the increasingly apparent implications of generative AI on business, society and politics have triggered responses from the arts community. Last summer, writers and actors unions went on strike largely to secure rules around the use of AI in the entertainment industry to protect human creators. Commercial artists working in videogame and media production, special effects, animation, illustration, comics and advertising lack that kind of unity and central organization, but are becoming increasingly outspoken, well informed and resourceful in their efforts to mitigate the negative impacts of generative AI, despite being up against the best narrative of inevitability that billions of dollars can buy.

Artist and activist Karla Ortiz

“Generative AI products are riddled with theft and legal problems,” said Karla Ortiz, a concept artist who is one of the named plaintiffs in class action suits against several of the companies developing generative AI technology. “There has to be a better way to implement this technology than a system that steals from artists for the profit of big tech companies. It’s disgusting.”

See full interview with Karla Ortiz here.

Others are active on social media, naming and shaming examples of AI-generated imagery that is infiltrating the culture, including artists who misrepresent work made with AI as their own and “tech bros” who welcome the replacement of “elitist” human artists with tools that de-skill the creation of artwork into “prompt engineering.” A Facebook group called “Artists Against Generative AI” counts over 160,000 members.

Now this effort is receiving support from an unexpected quarter: tech entrepreneurs and researchers building countermeasures to help creators and consumers restore some reality to an increasingly surreal AI-dominated landscape. These approaches fall under three main categories: “poisoning the well” using code that corrupts AI data models if images are scanned without permission; spotting the fakes using algorithms that can spot the fingerprints of AI at the pixel level; and authenticating the real by encoding original, human-produced images at the point of creation.

Poisoning the Well

Ben Zhao, professor of Computer Science at the University of Chicago, and developer of Glaze and … [+]

One of the most promising and popular countermeasures uses code embedded in the images that, if the image is used in AI data training without consent, “poisons” the sample, rendering it useless. The main tools for this, Glaze and Nightshade, were developed by a team at the University of Chicago led by computer science professor Ben Zhao.

“My focus has been on protecting human creators, especially those most vulnerable and least represented, such as artists, musicians, writers, choreographers, dancers, and voice actors,” said Zhao. “These groups are heavily impacted by generative AI in terms of employment, personal attacks using deepfakes and revenge porn, identity theft, phishing scams, and style mimicry. So, my recent work aims to defend these people against the abuses of AI.”

Zhao and his team were originally focused on the problems of AI-based facial recognition systems, but shifted focus toward artists in 2022 when the first generative art tool like Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and Dall-E2 first appeared. Zhao says he joined a town hall on AI convened by Ortiz, where over 500 artists shared their concerns about the emerging technology.

“After that call, we realized we could adapt our techniques to disrupt the training of AI on artists’ work,” he said. This led to the creation of the Glaze project and the technology called Nightshade. Artists can download the tool and apply it to their work before posting it online as a way to thwart the companies that hoover up images to train their models without consent or compensation.

“Think of Nightshade as technical enforcement of copyright,” Zhao says. “If you disrespect the copyright by training on content without the owner’s consent, it will start to eat your model from the inside and cause all sorts of corruption, leading to complete model collapse.”

The first public application of Glaze was on a work by Ortiz, who said she felt a tremendous surge of relief at the ability to share her artwork again on social media without fear of it being used to train robots designed to replace her.

“Musa Victoria,” an original artwork by Karla Ortiz, was the first public application of Glaze, … [+]

The uptake has been rapid and overwhelming. Zhao says it has been downloaded over 2.6 million times worldwide. Because the economics of the AI business dictate that companies continue to train, refine and deploy their models, the possibility that some of the “training data” (aka artwork) might include the “poison” code could be enough to force the big players to change their attitude about helping themselves to other people’s work.

Spotting the Fakes

Whereas Nightshade attempts to address the problem of data scraping and IP theft at the source, another countermeasure can help identify the output of generative AI systems by spotting the fakes. One of the leading tools is a free, online consumers service developed by Hive, a commercial company that builds AI models for content moderation and other industry-specific applications.

“A lot of people think AI systems are getting so good that it is, or will soon become, impossible to detect,” said Kevin Guo, cofounder and CEO of Hive. “We believe they are incorrect. It is definitely possible, and our tool has shown that you can differentiate with high fidelity and confidence.”

Guo says the Hive Moderation tool allows users to check images, text, video and other content to identify whether generative AI has been involved in the creation. Just drag and drop the sample onto the tool and it returns a confidence level between 0-100%, depending on how extensive the presence of synthetic content. Consumers are limited to several hundred tests per day, but Hive sells a commercial version for enterprise customers as well.

The Hive Moderation tool can help identify synthetic AI-generated content, even work that visually … [+]

“We’re a for-profit company building proprietary models, but we offer this for free because it’s a nice tool,” said Guo. “We want to help people, especially with the election coming up, be sure that what you’re looking at is real.”

While positively identifying AI-generated content is a moving target, Guo says the model rarely if ever produces false positives – that is, misidentifying human-created work as AI in cases where the artist has been heavily sampled by models. “To your human eye, the outputs can look similar, but they are not. The relationship is so distinct for these diffusion models that it is just completely different from how humans would create content.”

Verifying What’s Real

In addition to spotting the fakes, another tactic coming into use is authenticating human-created content at the source, so both artists and consumers can gain assurance, and control, over their original work.

One startup in the space, Swear, just released an app that watermarks photos and videos at the moment of creation to provide a baseline to identify any future modification, whether by traditional digital tools like Photoshop, or by AI.

“Swear is a company with a single focus: protecting the authenticity of digital content,” said Jason Crawforth, founder and CEO of Swear. “While you’re recording something—I’ll use video as an example since it’s the most evocative type of content—whether it’s on a smartphone, a police body cam, or a security camera, we capture frames, visual aspects, audio aspects, and metadata. For a smartphone video, for instance, we create a fingerprint of every frame in real time. This fingerprint, or hash, is a one-way formula that maps every pixel of a frame. If even a single pixel is changed, the fingerprint changes.”

The main application Crawforth envisions for Swear is forensic, certifying the authenticity of surveillance video and other digital evidence used in legal proceedings, medical and scientific studies, logistics and finance. He also believes authenticating archival content will become important in the future, in cases where bad actors fabricate historical documents or imagery to create or enforce their own narratives.

“Our technology addresses several issues, including deep fakes and synthetic content,” said Crawforth, but added it is not necessarily a solution for artwork as opposed to photo or video content, since it does not include a way to incorporate its technology into art creation platforms.

For that scenario, we are starting to see some software makers respond to the challenges of AI by giving artists and their audiences more transparency into the way digital artwork is created. One of the first out of the gate with a potential solution is Magma, a collaborative creative platform that combines professional design tools with workflow and social media capabilities.

Magma, which had previously run afoul of the anti-AI art community for implementing a version of Stable Diffusion built on scraped content, recently deployed a feature developed by Story Protocol, which automatically tracks and tags the exact usage of AI in the creation of any image on the platform as a way of verifying compliance with copyright, workplace rules, ethical standards and transparency.

According to Story Protocol, “Programmability means giving creative assets built-in rights for enforcement, remixing, and monetization. Story Protocol allows creators to attach legally binding and automatically enforced rights onto their work through the blockchain. Creators seamlessly set the pricing and permission terms for how their work can be used. Anyone interested in using that work can then accept the terms and license it in a single click.”

“It’s something we offer our B2B clients like animation or game studios, who may have trained models on their house style,” said Magma CEO Oli Strong. “We believe AI will be part of the workflow of the future, but we want to make sure it is introduced in a safe, responsible and protective way.”

Strong says the technology assures the provenance of a piece of work so the artist can prove AI was not involved, or remove the layers and elements where it was. “We can literally produce a certificate that demonstrates the artist is responsible for each layer, and that no other technologies were involved,” he says.

Both Magma and Swear use blockchain as the method for registering ownership and authenticity, as it is the best way to provide an immutable, decentralized ledger for digital assets. That may get them into trouble with some artists who are as down on blockchain due to its association with scammers, cryptocurrency, NFTs, environmental impact and tech bros, as they are against AI.

Swear’s Crawforth acknowledges that recent business developments have brought the technology into disrepute, but contends it is just a tool for achieving the larger goal of authoritatively telling truth and reality from AI-generated fiction. “Our use of blockchain is simply a method to create a distributed ledger that no single entity controls,” he explained. “This ensures the authenticity and ownership of digital content without the environmental impact associated with cryptocurrency mining.”

Ragtag Rebels vs The AI Empire

None of these approaches offer any guarantees. The generative AI juggernaut is well funded and entirely convinced of its own inevitability. The performance and scale of blockchain may not be up to the task of authenticating so much content; AI developers are locked in an arms race to punch holes in technologies designed to slow them down. If all else fails, the financial might of the big players might be enough to “catch and kill” any remedies that prove especially effective.

Amid the hype, the demand for countermeasures serves to call attention the underlying ethics of a technology dependent on stolen (sorry, “scraped”) content for its raw material, whose essential value proposition is the displacement of human creators and the centralization of control in the hands of management. These tools may not be perfect, but they put some potent weapons in the hands of the ragtag group of rebels raging against the machine. Death Stars have been blown up with less.