Opinion | Where Am I From?

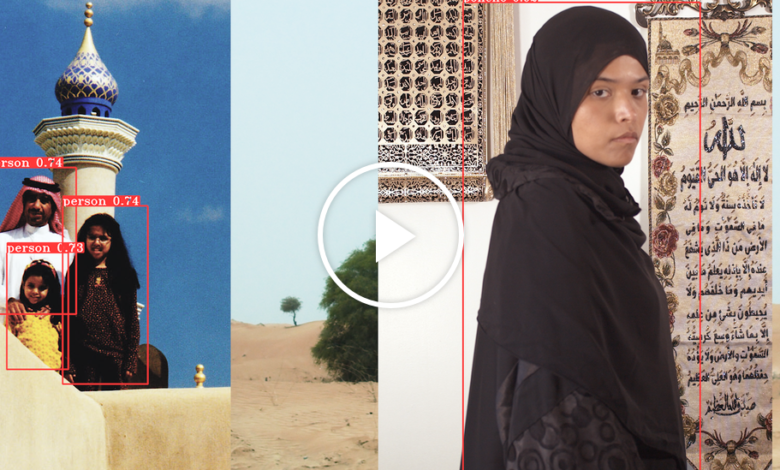

“Where are you from?” I don’t know where I’m from. Part of me is from Saudi Arabia, where I was born and where I lived for 13 years. But another part of me is from the U.S., where I immigrated to and have been living since then. “How can I help you?” I guess I want to remember where I’m from. For so many years, I pushed this part of me down, pushed it away so that I can fit in. Now that I’m older, I’m tired of doing this. I want to reconnect and remember the adan playing every morning, five times a day. “I found a castle made of wood. — 95.4 percent accuracy rate. Is this where you are from?” Why do I live in a world that doesn’t see me? Why do the forces that kept me hiding who I am persist today? We don’t have castles in my culture. Traditionally, our houses were built from mud, as it helps heat and cool during the harsh desert weather. I remember visiting these old buildings with my dad. We’d go to the park and walk around. You would see a sea of black and white. That’s how it was back home. Women wearing abayas and men wearing white thobes and checkered pink-and-black shemaghs. “I see women wearing hats. I’m detecting men wearing dresses, men with turbans, men with cloaks sitting in a garden. Is this where you are from?” My father wore a shemagh, not a turban. I remember always admiring its elegance, the way that men would adjust it on their heads, as if it were beautiful long hair, the way that they delicately folded it to frame their face. Putting on a shemagh represented tradition, elegance and power. “I don’t recognize this word, ‘shemagh.’” When I was 13 years old, I moved to America to get a better education. I moved to a place where no one looked like me. It was hard fitting in. I remember hearing Americans always being confused and thinking I’m Indian or Hispanic, that I didn’t look Arab. Maybe it was because I didn’t wear my hijab. What was I supposed to look like, then? What do you expect me to look like? “I’ve detected a tent in nature. My results indicate Northeastern United States. Is this where you are from?” Virginia was not home. I felt like an alien, an intruder. Every night I would lay down in my dorm room and remember what was previously home. I would feel the distance that I created, replaying my childhood, my old school, the old uniform I used to wear and my old routines. As I grew older in America, I felt that distance from home increasing and this deep hole getting bigger and bigger. “Calibrating. Where are you from?” Part of me feels like I’m not from one specific place, that I’m fragmented from different pieces. I’m from Basra, where my mom grew up. I’m from Baghdad, where my grandmother was born. Iraq has always held a special place in my heart. My mom’s stories were so beautiful and vivid. I wanted anything to go back and be a part of it. “Iraq. I found pictures of the Iraq. Is this where you are from?” Iraq was never like this. My Iraq is different. My perception and memories of it are different. Mama, tell me about Basra. “According to my search results, The Iraq is classified as Level 4 travel risk, due to terrorism, kidnapping, armed conflict and civil unrest. Is this where you are from?” “Saving new information. Your mother is from Basra. You are not from the Iraq. You are not from the United States. You are not from the Middle East. I don’t know how I can help you. I don’t know where you are from.” This question has been very hard for me to answer. Is there one word or place that defines my identity? Is my lived experience summarized into an image or a piece of clothing? I am from the flowers that bloomed in my mother’s garden in Basra. I’m from the rivers of Tigris and Euphrates, where my mom crossed every single day to school. I am from the dark black abayas of Saudi Arabia, the checkered pink- and-white shemaghs of Riyadh. I’m from the smell of incense coming into the house. I speak Arabic with Iraqi and Saudi tones. I speak English with an American accent. I’m from the woods of Virginia, the grapes of Iraq. My mom always said,