SBU’s IV Ramakrishnan scores $1.5 mln grant to design robotic arm for people with ALS

By Daniel Dunaief

Caretakers of those with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (or “Lou Gehrig’s disease”) have an enormous responsibility, particularly as the disease progresses. People in the latter stages of the disease can require around-the-clock care with everything from moving their limbs to providing sustenance.

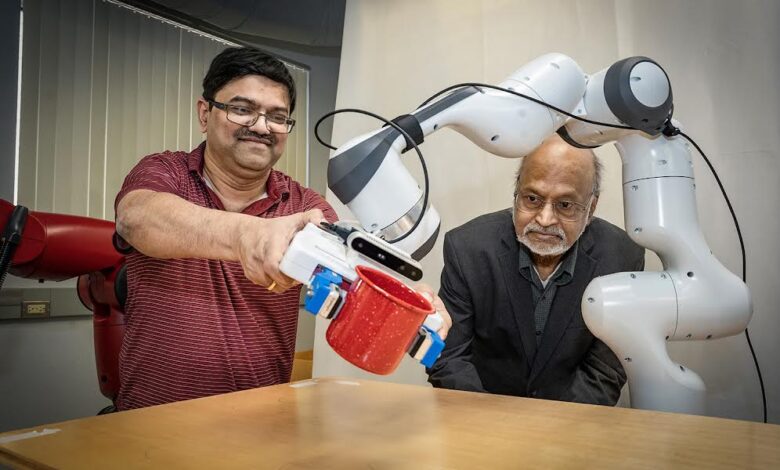

IV Ramakrishnan, Professor of Computer Science and an Associate Dean in the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Stony Brook University, recently received a $1.5 million grant from the U.S. Army to lead a team that is building a Caregiving Robot Assistant, or CART, for ALS patients and their caregivers.

The grant, which is for three years, will cover the cost of building, testing and refining a robot that a caregiver can help train and that can provide a helping hand in challenging circumstances.

Using off the shelf robot parts, Ramakrishnan envisions CART as a robotic arm on a mobile base, which can move around and, ultimately, help feed someone, get them some water and help them drink or open and close a door. They are also developing a special gripper that would allow the robotic arm to switch a channel on a TV or move a phone closer.

In working through the grant process, Ramakrishnan emphasized the ability of the robot, which can learn and respond through artificial intelligence programs he will create, to take care of a patient and offer help to meet the needs of people and their caregivers who are battling a progressive disease.

“As the needs evolve, the caregiver can show the robot” how to perform new tasks, Ramakrishnan said.

The project includes collaborators in Computer Science, Mechanical Engineering, Nursing, the Renaissance School of Medicine, and clinical and support staff from the Christopher Pendergast ALS Center of Excellence in the Neuroscience Institute at Stony Brook Medicine.

At this point, Ramakrishnan and his team have sent out fliers to recruit patients and caregivers to understand the physical challenges of daily living.

Ramakrishnan would like to know “what are the kinds of tasks we should be doing,” he said, which will be different in the stages of the disease. They know what kinds of tasks the robot can do within limits. It can’t lift and move a heavy load.

Once the team chooses the tasks the robot can perform, they can try to program and test them in the lab, with the help of therapists and students from the nursing school.

After they develop the hardware and software to accomplish a set of actions, the team will recruit about a dozen patients who will test the robot for one to two weeks. Members of the ALS community interested in the project can reach out to Ramakrishnan by email.

A biostatistician will be a part of that group, monitoring and calculating the success rate.

At this point, the development and testing of the robot represents a pilot study. After the group has proven it can work, they plan to submit a follow up proposal and, eventually, to apply for approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

Ramakrishnan estimates the robot will cost around $30,000, which is about the same cost as a motorized wheelchair. He is unsure whether Medicare will cover this expense.

As a part of the development, Ramakrishnan recognizes that the first goal, similar to the Hippocratic Oath doctors take, is to do no harm. He and his team are incorporating safety features that make the robot withdraw automatically if it gets too close to someone.

A key part of the team

Vibha Mullick, a Senior Web and Database Analyst in Computer Science and resident of South Setauket, will be a key team member on the project.

Mullick has been caring for her husband Anuraag Mullick, who is 64 and was diagnosed with ALS in 2016. Anuraag Mullick is confined to a wheelchair where he can’t swallow or breathe on his own.

“My husband also wants to participate” in the development, said Mullick, who spends considerable time reading his lips.

Caring for her husband is a full-time job. She said she can’t leave him alone for more than five or 10 minutes, as she has to suction out saliva he can’t swallow and that would cause him to choke. When she’s at work, a nurse takes care of him. At night, if she can’t get a nurse, she remains on call.

If her husband, who is in the last stage of ALS, needs to turn at night, use the bathroom or needs anything he makes a clicking sound, which wakes her up so she can tend to his needs.

“It tires me out,” Mullick said. In addition, she struggles to take care of typical household chores, which means she can’t always do the dishes or wash the laundry. She suggested a robot could help caregivers as well as ALS patients.

In the earlier stages of ALS, people can have issues with falling. Mullick suggests a robot could steady the person so they can walk. She has shared the news about the project with other members of the ALS community.

“They are excited about it and encouraged,” she said.

Origin of the project

The idea for this effort started with a meeting between Ramakrishnan and the late Brooke Ellison, a well-known and much beloved Associate Professor at Stony Brook University who didn’t allow a paralyzing car accident to keep her from inspiring, educating and advocating for people with disabilities.

Encouraged by SBU Distinguished Professor Miriam Rafailovich, who was a friend of Ellison’s, Ramakrishnan met with Ellison, whose mother Jean spent years working tirelessly by her side when she earned a degree at Harvard and worked at Stony Brook.

Ramakrishnan, who developed assistive computer interactions technologies for people with vision impairments, asked Ellison what a robot arm could do for her and mean for her.

He recalled Ellison telling him that a robot arm would “transform my life,” by helping feed her, set her hair, or even scratch an itch.

“That moved me a lot,” said Ramakrishnan.

While CART will work with one population of patients, it could become a useful tool for patients and their caregivers in other circumstances, possibly as a nursing assistant or for aging in place.

Road to Stony Brook

Ramakrishnan, who is a resident of East Setauket, was born in Southern Tamil Nadu in India and attended high school in what was then called Bombay and is now Mumbai.

He earned his undergraduate degree from the Indian Institute of Technology and his PhD from the University of Texas at Austin.

Ramakrishnan is married to Pramila Venkateswaran, an award-winning poet and is retiring this summer after 33 years as a Professor of English at Nassau Community College. The couple has two grown children, Aditi Ramakrishnan, who is a physician scientist at the Washington University in St. Louis and Amrita Mitchell-Krishnan, who is a clinical pediatric psychologist.

As for the work on CART, Ramakrishnan is eager to help patients and caregivers. The ultimate goal is to “reduce the caregiving burden,” he said.