Solar-Powered Off-Road Camper Built by Dutch Students

At the 2021 international motor show in Munich, BMW, with great fanfare, unveiled the iVision Circular concept car, designed for “the circular economy,” an eco-movement buzzword for recycling old stuff into new stuff using minimal energy. The iVision was the model of what the future of automobiles could be, except for one thing. It couldn’t move unless pushed, pulled, or trailered. It had no motor.

Still, BMW might have legitimately declared iVision a conceptual breakthrough except for one other thing. A group of students from Eindhoven University in the Netherlands had done it first, in 2018, and done it better. Their car of recyclable materials—the composite chassis was largely derived from sugar beets—could drive 240 miles on a charge and achieve top speeds of about 60 mph.

Just about every year since 2013, Eindhoven students have built operational concept cars to prove that eco-friendly design is within the reach of major manufacturers if they would only try (yes, you detect a hint of gleeful shaming; the students tend to go full Greta Thunberg with eco-enthusiasm).

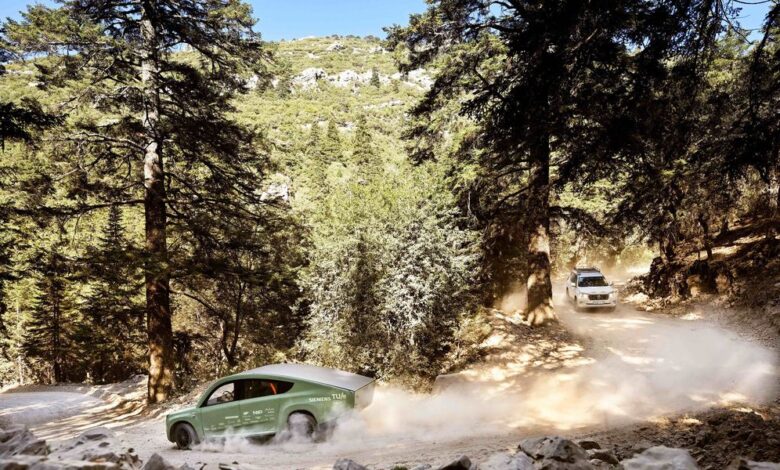

The most recent achievement, a two-seat all-terrain camper dubbed Stella Terra, made a 1000-kilometer (621-mile) on- and off-road trip through Morocco to the Sahara Desert, powered entirely by onboard solar panels. Claimed to be a first, Terra, as the students call it, has a theoretical top speed of 90 mph, and a range of 440 miles—if it’s sunny.

The secret to its success is the uniquely efficient integration of off-the-shelf components, computer programming, a bespoke power management system, and 22 highly caffeinated students.

The students dream up their own projects from cars, to drones, to medical devices. Success is not a given, said Madis Talmar, a professor who oversees the student programs. But the car projects “have succeeded nine times so far,” he said, “and that is something of a miracle.”

Two Eindhoven teams concentrate mostly on passenger cars, TU/Ecomotive, which has produced a car of recycled trash, one that could go 250 miles on the energy equivalent of one gallon of gas, and one forged largely on a 3D printer. Then there is Solar Team Eindhoven, which—until now—designed sun-powered cars to compete in Australia’s World Solar Challenge, a 3000-kilometer (1864-mile) race. Eindhoven won its class in four consecutive challenges.

Last year, Solar Team Eindhoven felt there was nothing to prove by racing again. Instead, it would build a utilitarian vehicle, a solar powered off-road camper, and prove it was on- and off-road worthy. “That’s the story we want to tell,” said Thieme Bosman, PR manager for the project. “That this is possible right now.” Take that, Detroit.

For a full year, team members suspend studies (still paying tuition), and spend days and nights squeezed in around computers, in meetings, consulting manufacturers and startups. Sardined into an under-sized garage, they worked in secret, commonly turning in 12- and 16-hour days, eventually requiring a day shift and night shift to complete construction.

Project teams start recruiting at student orientation, scouting for future engineers in software, thermal dynamics, aerodynamics, structure, and electrical, but also for specialists in design, finance, PR, and events marketing. Those skills are secondary to being a quick study and likable. “It’s not, ‘We know someone who knows how to do this [one thing] very well,’ but someone who can learn quickly, and fits well with the team,” said Bosman, who had set his sights on building a solar car back in elementary school.

Projects begin with a blank slate. “We knew we would do something with the power of the sun and mobility,” but that was the only limitation, said Bosman. Initial ideas included various solar cars, solar Tuktuks, and a solar submarine, which was cast off as impractical. The solar-powered off-road camper got the nod.

But how to build it? The guiding principle was to minimize energy use. Weight savings was top priority. Reducing rolling- and wind resistance was crucial to the extent of replacing sideview mirrors with tiny cameras. A pop-up camper back created enough room for two sleeping bags (where knackered students occasionally napped during construction), but closed down to beat drag underway.

Hub motors were chosen as lighter and more efficient than a single motor and drivetrain layout. But four-wheel drive or two? It was, after all, and off-roader. Four-wheel drive might dig a car out of a bog, they reasoned, but a lighter car might not bog down in the first place. Having two front motors would save money, allow shorter cable runs, save weight and reduce electrical transmission loss. Two motors it was.

Students innovated lightweight parts. The dense battery firewall, for instance, was swapped for a honeycomb sandwiched between two aluminum plates treated with an advanced fireproof coating. It was safety tested by an outside lab because, “We did not have the ability to make such a big fire at our place,” said Bob van Ginkel, technical manager for the project.

The solar cells created particular challenges. The most efficient panels, made for space, were too expensive. More economical cells make less power and are typically protected by heavy, inflexible glass. The students solved the problem with panels that employ a novel film coating, creating a lightweight protective barrier that also captured more light than glass. The coated cells remained flexible, so they could conform to the car’s aerodynamic roof and hood.

The bigger issue with the panels was maxing out the power to the batteries. Batteries charge best from a consistent power feed, which solar cells can’t provide. Many variables cause cell power to fluctuate—temperature, and passing clouds, to name two. It demands a system to manage how the solar power is doled out.

Off-the-shelf power management systems were either too big or couldn’t handle 400 volts put out by the panels. “So we completely designed it ourselves,” said van Ginkel.

The resulting half-pound of 7.9- by 7.9-inch printed PC boards were 97 percent efficient, equal to the best of the larger residential converters. It would later prove so efficient that the car’s regenerative brakes had to be dialed back at times because the battery was too full to take a charge.

Production was a trial and error process caused both elation and anguish. “A very big moment was the motor spinning for the first time,” said van Ginkel. On that day, the team anxiously gathered, not quite sure what to expect from the patchwork system. They collectively held their breath as the accelerator was gently pressed, there was a slight hum, the motors turned, and a triumphant cheer erupted. “If it worked outside the car,” said van Ginkel, “it will work inside the car.”

When the nearly complete Terra was finally rolled out for its first test drive the mood was festive and confidence was high. “It was indeed like launching a ship,” van Ginkel said. When the accelerator was pressed, the motors hummed, the wheels turned, and as expected, Terra moved—but backward. The room stilled with a mortified silence. “After about 10 seconds of that, we burst out laughing,” said van Ginkel. The motors were swapped left to right, problem solved.

The completed Terra still needed a testing ground. “How do you prove that a solar off-roader can work?” said Bosman. They chose Morocco, because it wasn’t hard to ship Terra there. Second, “Every couple of hundred kilometers, there is a different landscape,” said Bosman. “And sun.” The goal was to drive more than 600 miles from Tangiers to the Sahara Desert over 10 days entirely on solar power.

Sun was plentiful but so were wheel-mangling potholes. The team was dogged with manageable technical problems to solve daily, but nothing was so daunting as the potholes. Within days, road ruts had snapped a knuckle on the steering assembly, which, with some scrambling, they were able to repair.

After that a strategy emerged. An advance car radioed back to warn Terra of upcoming hazards. But on the fifth day, the inevitable happened. Wheel met pothole and the steering tie-rod snapped like a stale stroopwafel.

Unable to make a repair with the gear on hand, the students sat stranded by the roadside, deflated. After nine “miracle” years of successful concept cars, and after a dismissive withdrawal from the Australian competition where it was the odds-on favorite, the Eindhoven Solar team was positioned to make history as the car program’s first big failure. “When we had to trailer the car to the accommodation,” said Bosman, “that had a real effect on the team dynamic and team spirit.”

Dispirited but unwilling to quit, the students mounted an all-hands-on deck effort. The engineering team CAD designed a reinforced steering mechanism. Coincidentally, a videographer was headed from Eindhoven to meet the team the next day. The videographer could bring a replacement part—if they could get it made immediately. A frantic phone call was placed to a Netherlands fabricator who agreed to CNC the redesigned tie rod overnight.

The miracle was miraculously intact. The team later calculated they had enough battery power in reserve to drive 30 miles back to the site of the breakdown and resume the route uninterrupted.

After the tie-rod drama, the uneventful final five days would seem almost anticlimactic. And yet, when the students did reach the Sahara, a year’s worth of late nights, anxieties, near failures, and a final success erupted into a spontaneous riot of joy, students pouring sand over one another, summersaulting through the dunes, hugging, cartwheeling, screaming, and taking turns flooring Terra across the sand like a dune buggy.

One final ritual was held. Solar races always finished with a jump in a fountain or an ocean. So at the hotel, the students clasped hands, and jumped fully clothed into the pool. It failed to wash off all the sand. “A week later,” said van Ginkel, “I could still find sand in places where I didn’t think there could be sand.”