The First Attempt To Patent An Automobile In America Was Laughed Out Of Congress

As I think I’ve revealed before, I have a sort of obsession with the really early automobiles, and especially regarding my longstanding beef with Mercedes-Benz for claiming that they invented the automobile, which they very much did not. The very early history of automobiles is a rich, complex, strange, and wonderful tapestry, and it brings me a lot of joy when I find interesting bits of it to share with you. This particular fact I think is a very significant one, and one that highlights both an often-overlooked very early motoring pioneer and reveals how strange and unimaginable people once thought about the very idea of a self-propelled wheeled vehicle. The person I want to tell you about is Nathaniel Read, and he could have had America’s very first automobile patent, if only everyone didn’t think it was such an absurd joke.

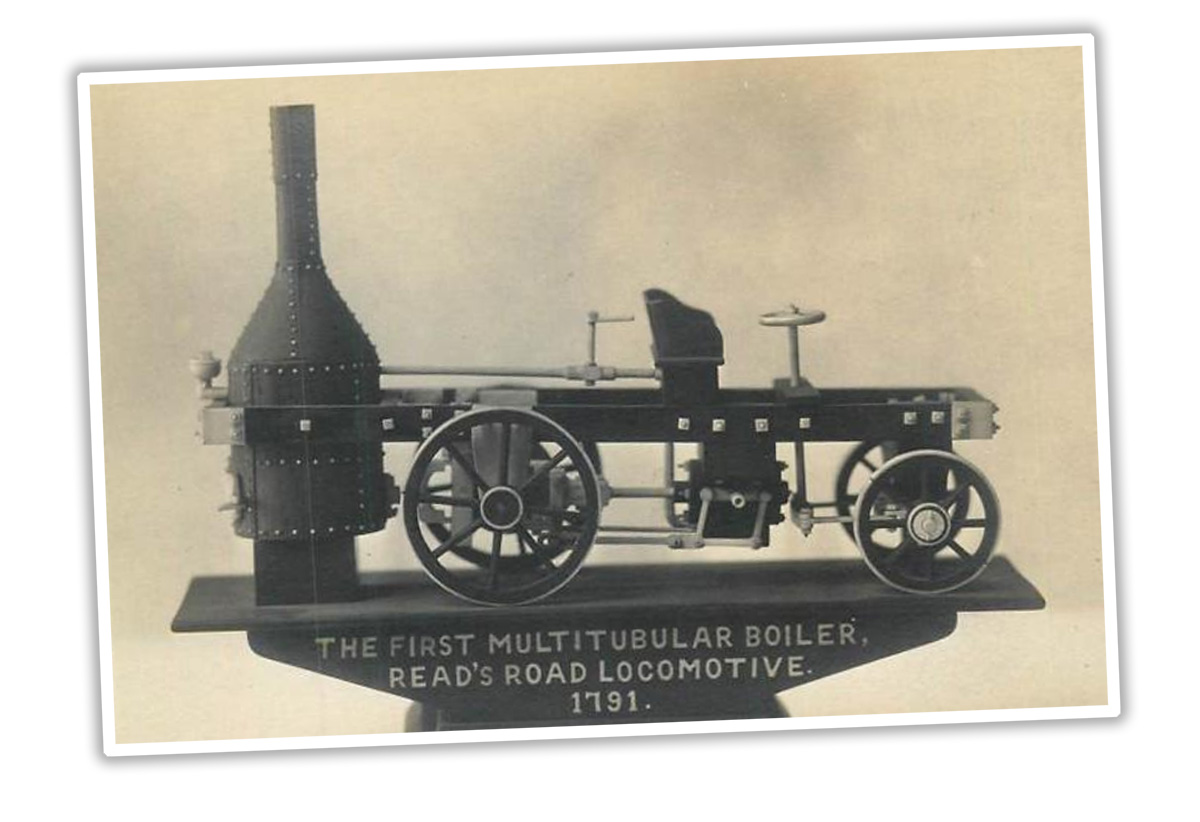

Nathaniel Read was born in 1759, ten years before Nicholas-Josef Cugnot first demonstrated the very first actual automobile, the Cugnot Steam Drag. So, he wasn’t the inventor of the very first automobile, and, really, there’s no evidence he actually built any actual running cars at all, but he did design one that was very plausible and could have worked, but even more significantly, he developed the Watt steam engine into the first true high-pressure steam engine and came up with the multi-tubular boiler that became the standard concept for steam vehicles ever after.

![]()

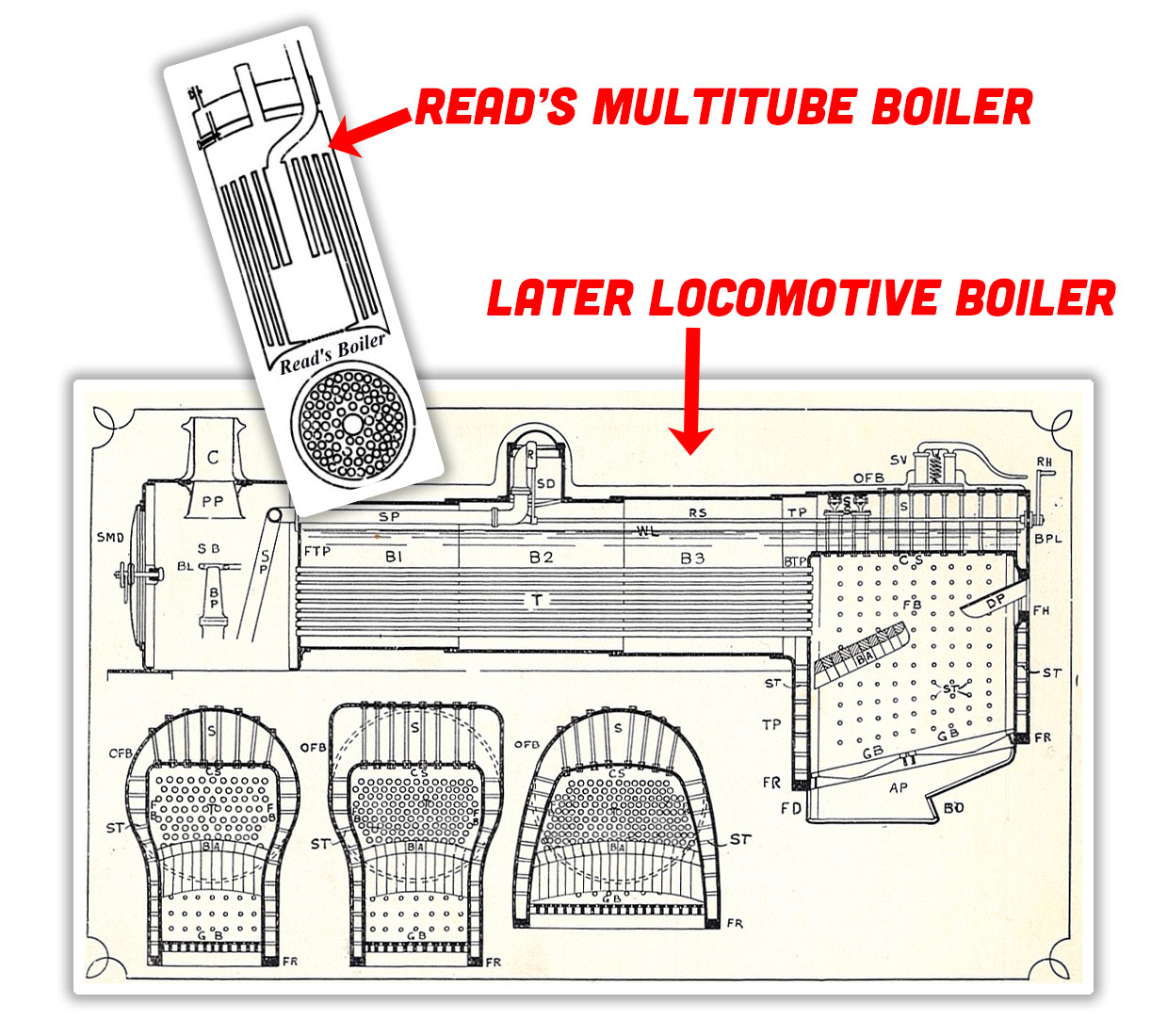

The multi-tube boiler placed the water to be boiled within the fire, not just in a mass above it, via a network of water tubes inside the boiler that exposed more water to more heat, allowing for a boiler that heated water much faster and could be much smaller and more suited to vehicles than previous boiler designs. Just to see, in the most basic way, how Read’s multi-tube boiler changed steam engine boiler design so significantly, here’s a very schematic image of Read’s boiler and a much later steam locomotive boiler:

See? It’s all tubes! Without this innovation, high-pressure steam engined vehicles, whether land or sea or the murky places in between, would not have caught on in the way they did.

Nathaniel Read never quite got the recognition he deserved, but he did live long enough to see his ideas put into practice. In the book with the very catchy title NATHAN READ: HIS INVENTION OF THE MULTI-TUBULAR BOILER AND PORTABLE HIGH-PRESSURE ENGINE, AND DISCOVERY OF THE TRUE MODE OF APPLYING STEAM- POWER TO NAVIGATION AND RAILWAYS, written by his nephew, David Read, there is a quote from Nathan Read where he reflects on his contributions:

“I was too early in my steam projects. The country was then poor ; and I have derived neither honor nor profit from the time and money expended on them. But it is gratifying to know that the simple machinery which forty five years ago (without any knowledge of its having ever been used for that purpose) I selected as the most eligible for propelling boats through water, has been since that time successfully used in every quarter of the globe for that purpose. I was, however, still more gratified last spring, in viewing a locomotive engine, capable of moving a mile in two minutes, put in operation by steam generated in a portable boiler, constructed essentially on the same principle with one which I invented for that and other purposes about forty-six years ago, and for which I obtained a patent the first day that any patent was ever issued by authority of the United States.”

This notion of being too early, being too far ahead of the curve, is one that should be familiar to those of you who are interested in the history of technology. Sometimes you can be too much of a pioneer, to the point that, while your work may be the seed from which so much later developed, your innovations happened before people were really ready for them, and while you may earn some notoriety and credit by people who really know their stuff, the mainstream world likely will not know who the hell you are.

For a more recent example of this, consider the in-the-know famous Mother of All Demos, a demonstration given by Douglas Engelbart in 1968 that introduced hyperlinks, videoconferencing, email, graphical user interfaces, and the freaking computer mouse. Pretty much all the key ways you interact with your computer today, this man Engelbert came up with.

And, while, sure, he’s well known and respected, between his name and, say, Steve Jobs or Bill Gates, which names do you think the average person associates with modern computing?

Here, you should watch this demo if you haven’t, because it’s absolutely incredible:

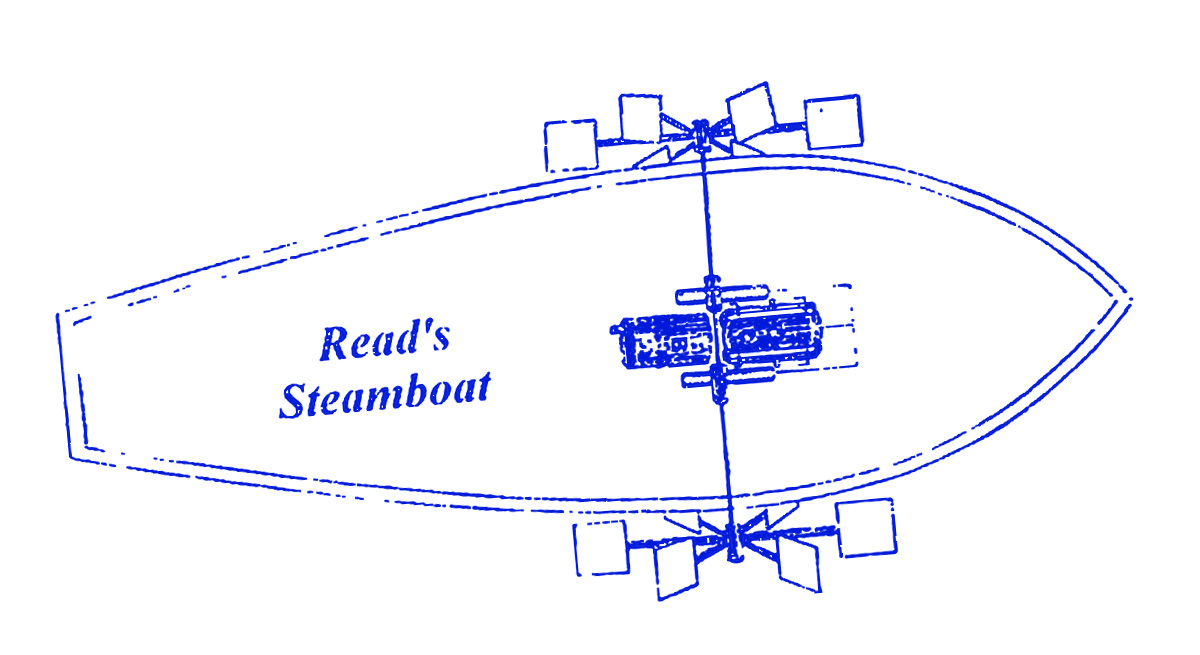

But, of course, that’s a rough nearly couple centuries after what we’re talking about. We’re talking about how Nathan Read designed an automobile that used his improved boiler design and high-pressure steam engine. He also designed a steamboat, and was able to easily secure a patent on that, and I think the reasons why are interesting.

The general retelling of Read’s attempts to patent his inventions, which would have happened at the absolute very beginning of the United States Patent Office, is that while his boiler and steamship designs were accepted fairly easily, Congress “ridiculed” the idea of a steam-powered road vehicle so much, he withdrew his patent application. Other sources do suggest that a patent on the steam carriage was given in 1790, and there is a quote from Read himself describing the process:

“I have a distinct recollection , when my petition to Congress was read in Congress Hall by the Clerk of the House of Representatives, that when he came to that part which related to the application of steam to land carriages, a general smile was excited among the members, and the idea was considered there and at Salem, where I had a model of a steam-carriage constructed, as perfectly visionary.”

I think what is meant when Read says the idea was considered “perfectly visionary” is what we today might describe as “fantastical” or “delusional.” And, I think “a general smile was excited among the members” is indeed a genteel way of saying “they laughed at me.”

This is further supported by references from letters in the National Archives, one of which, when summarizing a letter from Joseph Willard, who was sending Read’s plans and drawings to Thomas Jefferson, summarizes the resulting congressional patent hearing thusly (emphasis mine):

Nathan Read (1759–1849), a minor New England inventor, presented his petition to Congress for a patent on his inventions on 8 Feb. 1790, some time before TJ received the present letter: these included plans for both a steamboat and steam road carriage. The latter was ridiculed to such an extent that he abandoned it and the former was based on a paddle-wheel arrangement not original with him, in consequence of which he presented a new petition on 1 Jan. 1791 and seven months later was granted letters patent for “a portable multitubular boiler, an improved double-acting steam engine, and a chain wheel method of propelling boats” ().

I also take some issue with the characterization of Read as “a minor New England inventor.” Without his multitubular boiler, the railroad revolution wouldn’t have been possible, you smug National Archives nerds!

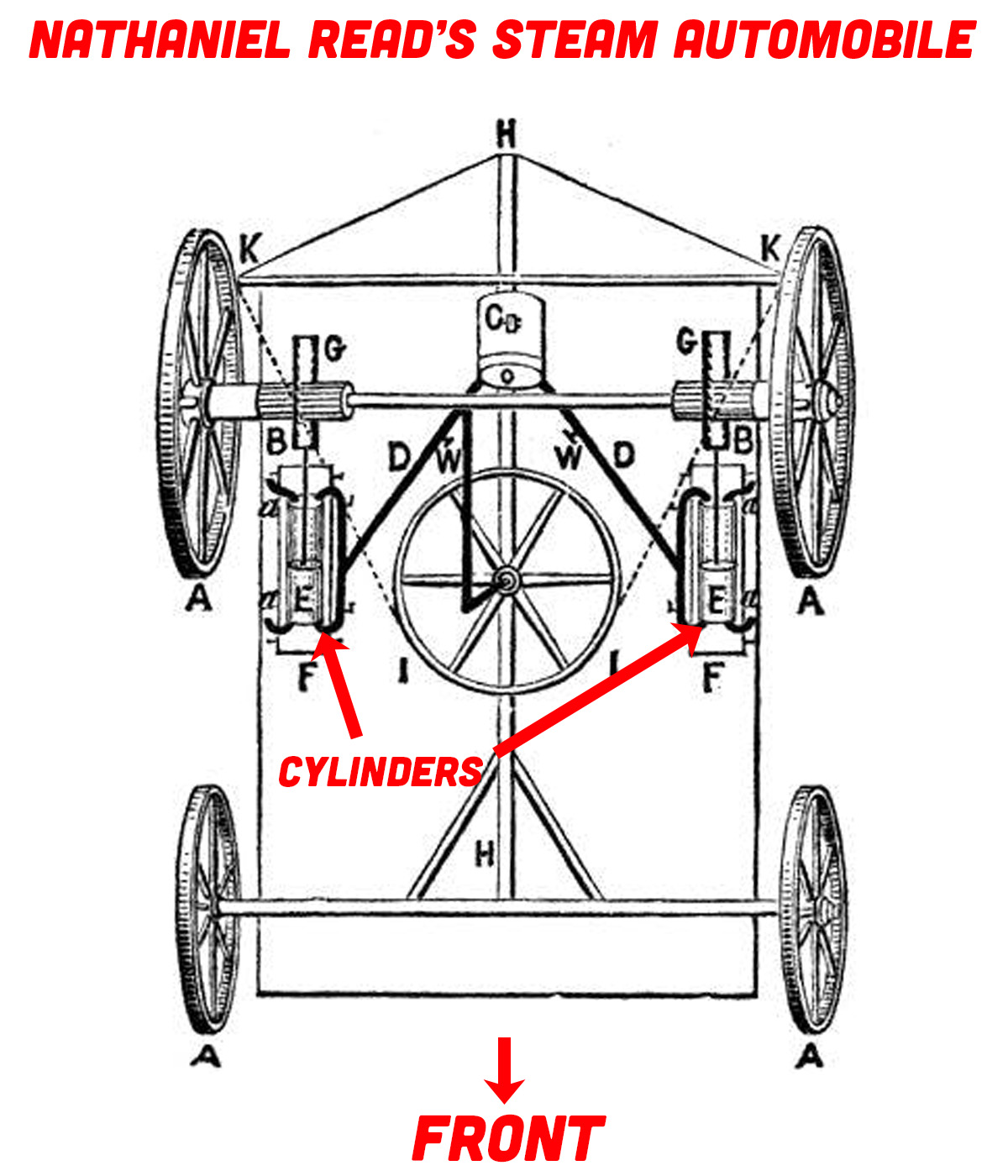

It’s also frustrating to see this because Read’s steam carriage plans were actually quite clever:

His design was pretty straightforward and simple, and used a pair of steam-driven cylinders that acted on pinions on the rear wheel axles (B) via a ratcheting system (G). The boiler (shown much smaller in this diagram) is C, and you can see how it feeds the twin cylinders via steam pipes (D). The exhaust pipes (a) were even designed to point backwards, in case any action-reaction motive force from the steam exhaust could prove helpful.

There’s a model of what the Read Steam Automobile could have looked like, and, really, for 1791, that’s a pretty advanced car. It’s operable by one person, has a steering wheel, mid-engine, rear-wheel drive – why it’s basically a late 1700s Porsche Boxster!

The fact that this was the object of ridicule and a steamboat – which was really just a slightly different packaging of the same basic technology – was treated with the seriousness and respect it deserved is fascinating to me. I wonder how much of it has to do with the fact that sailing vessels have always at least had the appearance of self-propulsion, even if it’s pretty muddy about if actually is, something I’ve wondered about before. You can see a boat move, seemingly on its own, with wind or current. And while a carriage sent down a hill will roll with gravity, the idea of a carriage moving on its own, not pulled by some hapless animal, perhaps was too strange a concept for those old powdered-wig and snuff-addled late 1700 congresspeople to imagine.

What if a patent had been granted, and before 1800 Read had gone into business building steam vehicles? Would we have had a boom in steam bus service, like England did in the 1830s?

Would rail development have been delayed, or even skipped over in favor of steam road vehicles? Who knows? We’ll never really know, all because the members of Congress thought the idea of a self-propelled road machine was just too ridiculous to even consider.

Hell, now you can get a patent for an NFT. That‘s the kind of shit they should be laughing out of the patent office.

Support our mission of championing car culture by becoming an Official Autopian Member.

The End Credits For The Old ‘Speed Racer’ Show Featured Some Shockingly Good Early Automotive History

Here’s A Look At A Working Bus From 1833: Cars Before Cars

Is A Sailboat A Self-Propelled Vehicle? What About A Cable Car? Or An Elevator?

Got a hot tip? Send it to us here. Or check out the stories on our homepage.