The Power of Us: As EV demand slows, a new alternative fuel garners attention

ABC News is taking a look at solutions for issues related to climate change and the environment with the series, “The Power of Us: People, The Climate, and Our Future.”

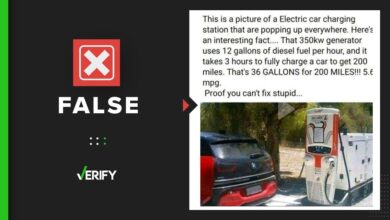

While electric vehicles’ share of the automotive market is still growing, the rate at which Americans are buying new electric vehicles appears to be slowing. Kelley Blue Book reports that just under 270,000 EVs were sold in the first quarter of this year. While that’s up nearly 3% from the first quarter of 2023, it’s down considerably from the last quarter of last year.

“Something I’ll say is that electric vehicles are for the patient,” says Oleksiy Golub, who’s driven EVs since 2020. Right now, he drives a Hyundai Ioniq 6. He says while he likes the car, it’s not without its frustrations, most of them having to do with charging.

A 2022 JD Power survey of more than eleven thousand EV and plug-in hybrid owners found that 20% of drivers who visited a public charging station ended up not charging their vehicle due to the technology malfunctioning or being out of service. While the public charging infrastructure has seen federal investment since then, with resulting improvements, Golub says public charging stations can still be finicky – and crowded.

“If there is one or two people in front of you, instead of staying at a charger for half an hour, 40 minutes, you stay there for that, like, times two or three,” he says.

That can make long-distance travel impractical, like when Golub tried to drive his previous EV, an older Hyundai Ioniq, from Philadelphia to Denver.

“I stopped during that trip seventeen times, forty minutes to an hour each, and twelve of those times were by a Walmart,” he tells ABC Audio, adding that as a result, “I know how to get around a Walmart like the back of my hand.”

A customer pumps gas at a gas station in Hercules, Calif., March 14, 2024.

David Paul Morris/Bloomberg via Getty Images

Golub considers himself an early EV adopter, someone who’s willing to deal with some of the frustrations that come with new technology. But more mainstream consumers generally have a lower tolerance for those frustrations.

In March, the Biden administration announced new Environmental Protection Agency regulations for vehicle emissions, which are less aggressive than the agency’s original proposal from last year. They also allow automakers more time to meet those targets.

Automakers like Ford and General Motors have said they’re using the extra time to re-invest in hybrid technology, which pairs electric motors with traditional gas engines. But others have focused on how to make the gas-burning vehicles that are already on the road greener.

Ralf Diemer is the CEO of the eFuel Alliance, a collective of about 180 companies aimed at advocating for liquid fuel that is developed in a carbon-neutral way.

“The end product actually, if you take the example of gasoline, is a gasoline which you can use in any current car on the road,” says Diemer.

Diemer says eFuels work the same way as existing gasoline and diesel does: it can be transported in tanker trucks to gas stations, where drivers can fill up and run their cars the same as if they were using traditional gas.

Meg Gentile is the executive director of the board of HIF Global, a company that runs the world’s first functional eFuels facility in southern Chile, and which itself is part of the eFuels Alliance. She tells ABC Audio that the recipe for making an eFuel starts with two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom: namely, water.

“Water is H2O, and it’s basically separating the H from the O,” says Gentile of the process, which uses an electrolyzer, which Gentile describes as a large metal machine about the size of a door.

“The water passes through two panels that have a metal sheet that is a good conductor of electricity, and then that electricity separates the molecule apart,” she says.

A fuel tanker truck drives on a highway in Tracy, Calif.

Adobe Stock

That produces hydrogen gas – the first ingredient in the eFuel recipe. Gentile says the next step is to harvest carbon from the atmosphere using renewable electricity: “We’re going to just take it from the air, because there is carbon dioxide in our air.”

Finally, HIF Global combines the hydrogen and carbon molecules to make a hydrocarbon.

“Hydrocarbon is also called fossil fuels or, basically, all the fuels that we use today in our cars airplanes and ships,” says Gentile.

However, the goal is to create hydrocarbon fuel in such a way that the pollutants that are emitted when it burns can be recaptured and made into more fuel, says Gentile.

“They’re considered carbon neutral because we captured CO2, we also re-emit the CO2 because the engine works in the exact same way, but we’re not bringing any new emissions into the atmosphere,” she says.

That’s important, according to Diemer, because the cars, airplanes, and ships that are currently in use likely aren’t going anywhere anytime soon.

“Most of [the cars on the road] have combustion engines,” he says. “They won’t disappear overnight, which means you would need a solution, at least in the short term.”

Kelley Blue Book reported last year that the average car on American roads is now twelve-and-a-half years old, while boats, on average, are in use even longer. Advocates like Diemer say while the broader transportation industry figures out a way to stop burning hydrocarbon fuels altogether, eFuel could make existing vehicles more environmentally friendly, either by mixing eFuels with traditional gasoline or by replacing it entirely.

But Diemer also notes that it’s not that simple. For one, eFuel is hard to come by. HIF Global’s facility in southern Chile is currently the only one of its kind, and it only sells to Porsche, another member of the eFuel Alliance.

Porsche vehicles are seen at the 2024 New York International Auto Show, March 28, 2024, in New York. The carmaker is a member of the eFuels Alliance.

Michael Dobuski/ABC News

Also, eFuel is expensive, at least for now, costing between twelve and fifteen dollars per gallon, according to Diemer.

“I like to think of it anywhere from twice the cost of gasoline today to as much as an order of magnitude more,” says Dr. Ian Rowe, a division director for the Office of Fossil Energy and Carbon Management at the U.S. Department of Energy.

Another challenge for eFuel that Rowe cites is whether the energy used to make it truly is green, as advocates insist.

“eFuels require a lot of renewable electricity, and until we can really deploy the amount of renewable electricity needed to make this feasible, it’s just not going to be able to make a huge dent,” he tells ABC Audio.

Diemer says that could all change as more companies invest in new technology, build out production facilities, and mix eFuel into the existing fossil fuel supply chain. But that would require companies to make the investment risk.

“It’s about how to overcome first-mover risks and problems,” Diemer says. “Then, of course, the challenge is to really trigger the big investment to achieve scale effects in this production.”

Rowe adds that the cost of eFuels right now, plus the lack of investment to get them up and running at scale, means they don’t really make sense for use in normal internal combustion engine cars.

“I would say that it’s very difficult to see a scenario where eFuels could be deployed large-scale to meet something like the light-duty sector,” says Rowe. “However, I think there’s a reasonable path to meeting some of our heavy-duty needs.”

That means using eFuels to fuel things like passenger jets and cargo ships. But Rowe says that’s only going to happen if governments craft policies to incentivize the large companies that operate those vehicles.

“Basically, we need to make sure there’s policy ready that could accept eFuels once they’re ready to hit the market,” he says.

There’s already been some movement on this front. Both Rowe and Diemer cite incentives and tax credits included in the Inflation Reduction Act, signed into law by President Biden in 2022, as a step in the right direction. But Rowe says more needs to be done, at the highest levels of government and industry.

“What’s really going to be needed is a confluence of these technologies learning how to scale up, renewable electricity deployment, and policy coming into place that can support them,” says Rowe.

Hear the full story on ABC Audio’s Perspective podcast, below.