The Worst Part of a Wall Street Career May Be Coming to an End

Pulling all-nighters to assemble PowerPoint presentations. Punching numbers into Excel spreadsheets. Finessing the language on esoteric financial documents that may never be read by another soul.

Such grunt work has long been a rite of passage in investment banking, an industry at the top of the corporate pyramid that lures thousands of young people every year with the promise of prestige and pay.

Until now. Generative artificial intelligence — the technology upending many industries with its ability to produce and crunch new data — has landed on Wall Street. And investment banks, long inured to cultural change, are rapidly turning into Exhibit A on how the new technology could not only supplement but supplant entire ranks of workers.

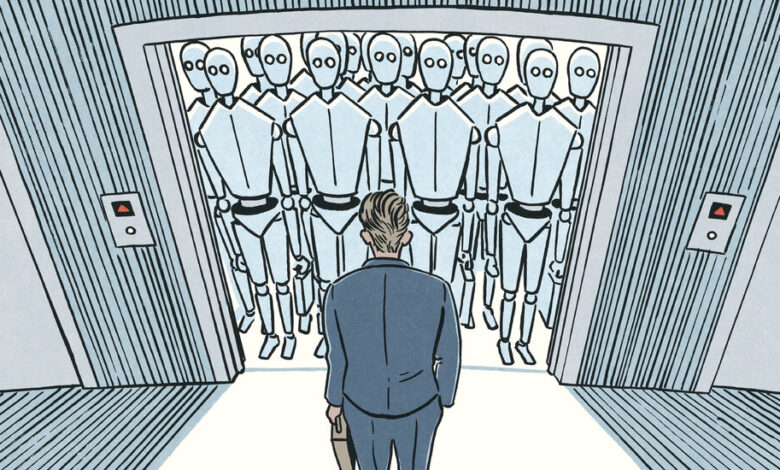

The jobs most immediately at risk are those performed by analysts at the bottom rung of the investment banking business, who put in endless hours to learn the building blocks of corporate finance, including the intricacies of mergers, public offerings and bond deals. Now, A.I. can do much of that work speedily and with considerably less whining.

“The structure of these jobs has remained largely unchanged at least for a decade,” said Julia Dhar, head of BCG’s Behavioral Science Lab and a consultant to major banks experimenting with A.I. The inevitable question, as she put it, is “do you need fewer analysts?”

Some of Wall Street’s major banks are asking the same question, as they test A.I. tools that can largely replace their armies of analysts by performing in seconds the work that now takes hours, or a whole weekend. The software, being deployed inside banks under code names such as “Socrates,” is likely not only to change the arc of a Wall Street career, but also to essentially nullify the need to hire thousands of new college graduates.

Top executives at Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley and other banks are debating how deep they can cut their incoming analyst classes, according to several people involved in the ongoing discussions. Some inside those banks and others have suggested they could cut back on their hiring of junior investment banking analysts by as much as two-thirds, and slash the pay of those they do hire, on the grounds that the jobs won’t be as taxing as before.

“The easy idea,” said Christoph Rabenseifner, Deutsche Bank’s chief strategy officer for technology, data and innovation, “is you just replace juniors with an A.I. tool,” although he added that human involvement will remain necessary.

Representatives for Goldman, Morgan Stanley, Deutsche Bank and others said it was too early to comment on specific job changes. But the consulting giant Accenture estimated that A.I. could replace or supplement nearly three-quarters of bank employees’ working hours across the industry.

Goldman is “experimenting with the technology,” said Nick Carcaterra, a bank spokesman. “In the near term, we anticipate no changes to our incoming analyst classes.”

This week, JPMorgan Chase’s chief executive, Jamie Dimon, wrote in his annual shareholder letter that A.I. “may reduce certain job categories or roles,” and labeled the technology top among the most important issues facing the nation’s largest bank. Mr. Dimon compared the consequences to those of “the printing press, the steam engine, electricity, computing and the internet, among others.”

Investment banking is a hierarchical industry, and banks typically hire young talent through two-year analyst contracts. Tens of thousands of 20-somethings (both from undergraduate and M.B.A. programs) apply for some 200 spots in each major bank’s program. Pay starts at more than $100,000, not including year-end bonuses.

If they persevere, they move up the ranks to associate, then director and managing director; a handful end up running divisions. Although grueling, the life of a senior banker can be glamorous, involving traveling around the globe to pitch clients and working on big-money corporate merger deals. Many who get through the two-year analyst program have gone on to become business titans — the billionaires Michael Bloomberg and Stephen Schwarzman began their careers in investment banking — but a majority will leave before or after their two years are up, bank representatives said.

There are jokes among junior bankers that the most common tasks of the job involve dragging icons from one side of a document to another, only to be asked to replace the icon over and again.

“One hundred percent drudgery and boring,” said Gabriel Stengel, a former banking analyst who left the industry two years ago. Val Srinivas, a senior researcher for banking at Deloitte, said a lot of the work involved “gathering material, poring through it and putting it through a different format.”

Gregory Larkin, another former banking analyst, said the new technology would start “a civil war” inside Wall Street’s biggest firms by tilting the balance of power to technologists who program A.I. tools, as opposed to the bankers who use them — to say nothing of technology giants like Microsoft and Google, which license much of the A.I. technology to banks for hefty fees.

“A.I. will enable us to do tasks that take 10 hours in 10 seconds,” said Jay Horine, co-head of investment banking at JPMorgan, describing analyst jobs. “My hope and belief is it will allow the job to be more interesting.”

A.I.’s impact on finance is simply one facet of how the technology will reshape the workplace for all. Artificial intelligence systems, which include large language models and question-and-answer bots like ChatGPT, can quickly synthesize information and automate tasks. Virtually all industries are beginning to grapple with it to some degree.

Deutsche Bank is uploading reams of financial data into proprietary A.I. tools that can instanteously answer questions about publicly traded companies and create summary documents on complementary financial moves that might benefit a client — and earn the bank a profit.

Mr. Horine said he could use A.I. to identify clients that might be ripe for a bond offering, the sort of bread-and-butter transaction for which investment bankers charge clients millions of dollars.

Goldman Sachs has assigned 1,000 developers to test A.I., including software that can turn what it terms “corpus” information — or enormous amounts of text and data collected from thousands of sources — into page presentations that mimic the bank’s typeface, logo, styles and charts. One firm executive privately called it a “Kitty Hawk moment,” or one that would change the course of the firm’s future.

That isn’t limited to investment banking; BNY Mellon’s chief executive said on a recent earnings call that his research analysts could now wake up two hours later than usual, because A.I. can read overnight economic data and create a written draft of analysis to work from.

A senior Morgan Stanley executive told employees in a January private meeting, a video of which was viewed by The New York Times, that he would “get A.I. into every area of what we do,” including wealth management, where the bank employs thousands of people to determine the proper mix of investments for well-off savers.

Many of those tools are still in the testing phase, and will need to be run past regulators before they can be deployed at scale on live work. Bank of America’s chief executive said last year that the technology was already enabling the firm to hire less.

Among Goldman Sachs’s sprawling A.I. efforts is a tool under development that can transfigure a lengthy PowerPoint document into a formal “S-1,” the legalese-packed document for initial public offerings required for all listed companies.

The software takes less than a second to complete the job.