There are more electric vehicles in Boston, but the region lags behind other metros

Electric vehicle sales have surged in the Boston area, making the region one of the biggest EV markets in the U.S. But experts warn that the pace isn’t enough to help the state reach its emission goals, or to catch up with other larger markets.

The number of electric vehicles in Greater Boston has more than quadrupled since 2019, according to data from the automotive market research firm S&P Global Mobility. The growth comes as the state works to meet climate goals that call for a 50% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030, and a transition away from gas-powered cars.

Last year, area drivers added 21,841 fully electric vehicles to the region’s roads, accounting for 8% of all new auto registrations. That’s up from just 4,901 EVs in 2019, as the zero-emission vehicles have steadily grown over the past few years.

Despite these gains, Greater Boston lags behind other major metro areas in making the shift to electric vehicles. The region ranks 15th out of the top 25 metros in the U.S. The West Coast, and California in particular, dominate the ranking. Electric vehicles make up 34.5% of vehicles in the San Francisco area — the highest of any metro region — according to the data.

“There’s a much greater alignment between the customer profile of the EV buyer and the West Coast buyer, especially the large metro areas in California,” said Tom Libby, an automotive analyst at S&P Global Mobility.

Libby said EV buyers typically skew towards people who are young, high income, male and Asian — demographics that are well represented in California. The electric vehicle market “really took off” with the growth of Tesla, which was headquartered outside San Francisco until 2021, Libby said. (The company is now based in Texas.) California has also been a leader in adopting alternative fuels and offering government incentives to get people to switch to electric cars and trucks, according to Libby.

Overall, the U.S. hit a milestone in 2023 with more than 1 million new electric vehicles sold — 7.6% of all cars — according to Kelley Blue Book estimates. But, the S&P Global Mobility data shows the spread of EVs is uneven and largely concentrated on the coasts, especially the West Coast.

At the state level, Massachusetts exceeds the national share of electric vehicles. In 2023, 12.5% of vehicles sold in the commonwealth were electric, according to Katherine Antos, undersecretary of decarbonization and resilience at the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs. State officials have made increasing EV adoption a priority to meet the state’s climate goals.

“In Massachusetts, like nationwide, transportation is the largest source of emissions and most of those emissions from the transportation sector come from passenger and light duty vehicles,” Antos said.

Massachusetts has hit some of its targets, but still has more work to do. The state surpassed it’s goal of getting 60,000 EVs on the road in 2022. By the end of 2023, there were over 100,000 EVs on Massachusetts roads, according to Antos.

The biggest challenges to getting more people to switch to electric vehicles remain cost and charging infrastructure.

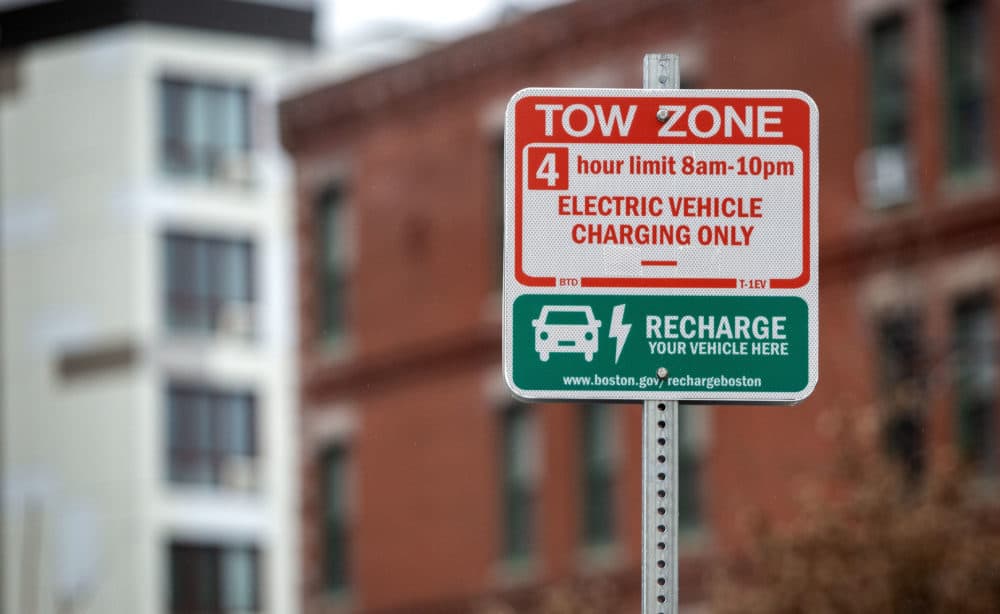

The state aims to have 15,000 public charging stations available by 2025, and 75,000 by 2030. But as of April, there are just 7,620 public chargers installed.

Public EV chargers are critical because about a third of Massachusetts residents lack off-street parking and face barriers to charging. Many people live in apartments or other multi-family units and can’t install personal chargers, according to Cutler Cleveland, a professor of earth and environment at Boston University and associate director of the Institute for Global Sustainability.

“A lot of people in Boston and many urban areas don’t have a garage, so they can’t put in their own charging infrastructure. And so that’s a real barrier,” Cleveland said. “That disproportionately hits low income households and households of color.”

The state’s climate report card noted more needs to be done to improve access to charging. Antos said the state is installing chargers at state facilities and providing resources to encourage municipalities to put chargers in place. The Department of Pubic Utilities also has a plan to install tens of thousands of new chargers over the next few years. And MassDOT is working to add charging stations along highways and key transportation corridors, according to Antos.

“They are in the process of putting in those high speed fast chargers so that when you are doing a longer trip, you can charge along the way,” Antos said.

Even as more chargers roll out, the cost of buying an electric vehicle remains a signifiant barrier. EVs are cheaper to maintain in the long-run, but the upfront costs are higher, according to BU’s Cleveland.

“On average, electric vehicles still cost several thousand more dollars than a regular vehicle,” said Cleveland. “And for many people, that is a deal breaker.”

The state offers rebates to help buyers offset the costs. There are also federal tax credits available. But Libby, the analyst, said the growth of EVs will “really improve” when prices come down.

“One can talk about reducing emissions, which is terrific, and we know we always have to go in that direction. But a lot of households don’t necessarily give that as much weight as they do what the monthly payment is,” Libby said.

Lowering the cost of EVs will largely depend on manufacturers, according to Libby. Tesla has been able to reduce prices on some of its models, but the company is in a “unique position” because it started as an electric car company, Libby said. Legacy manufacturers, “were not designed for electric vehicles” and are “very reluctant to lower prices” because EVs cost a lot to produce, Libby said.

Another limitation is the lack of variety among EV models available from carmakers. Without more options, consumers with specific needs will continue turning to traditional vehicles such as minivans and trucks, Libby said. Right now there are 70-80 electric vehicle models on the market, compared to about 400 in the U.S. new vehicle market overall, according to Libby. But that is changing, he added, as more EV models arrive.

With more electric vehicle models coming online, that could give customers more price points to shop from.

Massachusetts also adopted California’s clean car standards in 2023, which require car manufacturers to sell more electric vehicles over time. By 2035, the standards call for all new vehicles sold in the state to be electric.