Toyota was right to bet on hybrids, but no one is wrong to pursue the EV revolution (1)

Two separate surveys released in June emphasize Americans’ growing interest in hybrid cars, while those preferring EVs are fewer. This might seem like a blow in the face of EV proponents, but you’d be wrong to conclude that EV doom is near. Actually, it’s quite the opposite, however confusing it may sound.

According to probably the most well-known audit, tax, and advisory firm in the US and beyond, 38% of the respondents would choose a gasoline car, 34% would go for a hybrid one, and only 21% would buy a fully electric car. So, only 1 in 5 Americans is still convinced that an EV is the better choice.

Unsurprisingly, the percentages for standard gas-powered vehicles are even higher in the Midwest (40%) and Northeast (37%). However, I was baffled that the percentage of hybrid fans was the highest on the Western Coast (43%) despite California being the nation’s leader in EV sales.

The main EV-related issue seems to be recharging times: according to the survey, 60% of the respondents want electric cars to fully fast-charge in less than 20 minutes. KPMG notes that auto executives think that only 41% of prospective customers are interested in this.

Well, I’m surprised that low range and high prices are no longer the main issues. But, as I explained in another piece, most Americans don’t buy cheap or too-affordable new cars. Still, I’m pretty sure EV’s range anxiety and high price remain strong arguments for those interested in gasoline or hybrid cars.

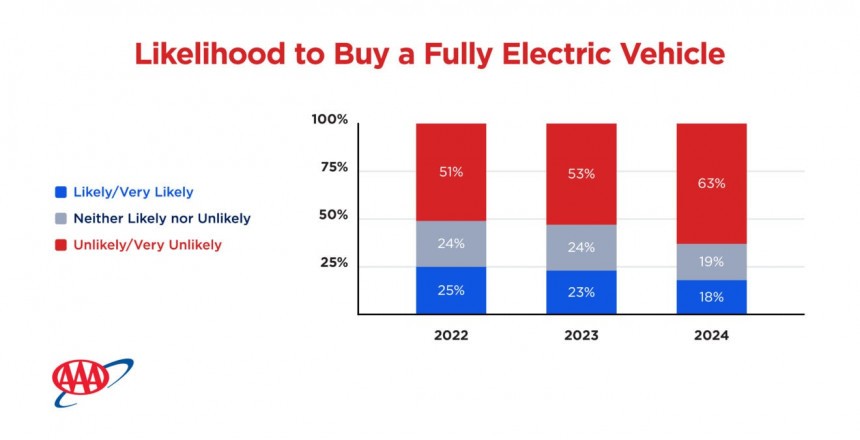

Now, let’s examine AAA’s findings on EVs in the most recent annual survey conducted on 1,152 adults. Consumer interest in purchasing a new or used electric vehicle declined from 25% in 2022 to 23% in 2023 and 18% this year. The yearly down trend is even sharper for those not even considering buying an EV.

As expected, “the main hesitations in purchasing an EV continue to be cost, lack of convenient charging options, and range anxiety.” Please observe that in AAA’s survey, the biggest issue is the cost, while the convenient charging options are only second – compared to KPMG’s survey, where charging is the most important issue.

As a result, 31% of the respondents are “likely” or “very likely” to buy a new or used hybrid car, which can overcome EV’s hurdles. It’s no wonder the Top 3 reasons for choosing a hybrid over an electric car emphasize long-distance travel suitability, lower dependency on public charging, and lack of concerns about running out of charge.

All of this sounds very logical, so it’s no wonder more and more car makers see hybrids as a longer-term play and not a transitional to zero-emission transportation. Of course, CEOs’ excuse might seem very reasonable: the slower-than-expected EV demand. Only they are wrong.

ICEVs vs. EVs? Or is it really ICEVs vs. hybrids?

As you know, Toyota is the top-of-mind when we talk about hybrids. The Japanese will soon celebrate three decades since the first mass-produced hybrid car was launched. Like the first electric cars a decade ago, the first-generation Toyota Prius was an expensive, high-tech, and hard-to-accept pioneer.

Nevertheless, the technology evolved, competition arose, and Toyota has sold more than 33 million cars fitted with hybrid powertrains in the last 27 years. It basically has a hybrid version for almost any of its models in its lineup, at least in the US.

Today, competition is fierce, as many other carmakers have entered the game. As a result, consumers have more options, and the difference between classic gasoline cars and similar hybrid cars shrunk a lot. Count in the pretty big savings in gasoline costs, thanks to better mileage, and here’s your answer for hybrids’ rising demand.

Basically, there’s no real competition between hybrid and fully electric cars, but between hybrid and gasoline cars. For instance, in the US, the most affordable Toyota Corolla is powered by a 2.0-liter gasoline engine, sporting a combined EPA fuel economy of 35 mpg. In comparison, the hybrid version is rated at 50 mpg – which is 40% better!

Compare the $24,595 basic price of the Corolla Hybrid with the $23,145 for the gasoline Corolla, same trim: the $1,450 difference means the hybrid version is roughly 6% more expensive. Considering an average price of 3.5 USD/gallon, the hybrid Corolla will break even after less than 500 miles!

It’s the same with the popular RAV4 SUV: the difference between the AWD entry-level trims is around $1,650 in favor of the gasoline version. But, as the hybrid’s EPA fuel economy is better (39 mpg vs. 30 mpg), this version will break even in roughly 600-700 miles. Now, tell me which is the better deal here.

No wonder Toyota ditched the non-hybrid versions for the 2025 Camry model year, and I suspect other models will soon follow suit. I mean, the nation’s best-seller Ford F-150 is becoming increasingly appealing in its hybrid version, which is similarly priced as the 3.5-liter EcoBoost gasoline version.

It almost makes no sense today to not buy a hybrid car. Of course, if you’re hunting for the cheapest new cars out there, you’ll only find gasoline powertrains. Currently, small sedans like the Nissan Versa or Mitsubishi Mirage start from under the $20,000 mark, but they’re simply city cars with a “tail” for a larger boot.

You can find better, safer, more spacious, and even more economical cars in the $20-25,000 range. KIA Forte, Hyundai Elantra, Nissan Sentra, Volkswagen Jetta, Toyota Corolla, Mazda 3, or Honda Civic are all competent compact cars, and their small-displacement gasoline engines usually give you 30-35 mpg fuel efficiency.

Of course, very attractive prices also mean trims with less equipment, and for now, hybrid powertrains are offered mostly in high-end trims. While the Corolla is an exception, the Elantra and Civic hybrid versions are in the $30,000 area. Therefore, these models take several thousand miles to break even compared to their gasoline versions.

Nevertheless, the trend for hybrids is very easy to spot, especially for cars costing more than $30-35,000. Classic gasoline engines simply can’t match hybrids’ better mileage, especially in city dwellings, where the ICE‘s efficiency is so poor. In this environment, a hybrid car works mostly on the electric motor, and this is where the problem arises.

Electrified cars are simply electrifying. In a good way

Most people who drive a hybrid car or at least had the chance to test one are usually surprised by the smooth ride of the powertrain. The car starts from a standstill with such ease (thanks to the electric motor’s torque), and you don’t hear that increasing roar of the internal combustion engine (because it rarely kicks in in the city).

That’s why the industry concluded that hybrids are mostly a transition to non-ICE cars, either electric or hydrogen fuel cell. At least, that was the general opinion before the current “slower than expected demand” for EVs and FCEVs…

In the meantime, hybrids evolved into plug-in hybrids to tackle the range anxiety concerns EVs are still plagued with. I won’t brag about the subterfuge industry used to lure customers—namely, those hilarious more-than-a-hundred MPG values. Nor will I discuss the over-optimistic assumption that customers will charge the battery most of the time.

There’s another point here: plug-in hybrids’ electric range is increasing yearly. For instance, several years ago, the first Mitsubishi Outlander plug-in hybrid had a range of less than 20 miles in full-electric mode, while the current generation almost doubled that value to around 38 miles.

This is very close to the average 39.7 miles an American driver covers daily, according to the most recent Department of Transportation statistics. I should mention that new plug-in hybrids from BMW and Mercedes-Benz have already passed the 50-mile electric range bar, and others will follow shortly.

Oh, and don’t forget another industry trend that I suspect will rise sharply in the next years: range-extender electric vehicles. The BMW i3 REX was a pioneer not only thanks to its quirky style but also because it fitted a little motorcycle engine in the back of the car as an electricity generator for the battery.

Currently, Chinese carmakers emphasize this EREV trend, which is pretty different from your “classic” plug-in hybrid powertrain – which is basically just a hybrid powertrain where you can also charge the battery from an external source. Still, the internal combustion engine is the workhorse most of the time, sending its power directly to the wheels.

In the range-extender variant, the internal combustion engine is used solely as a generator, never powering the wheels. This way, it works more efficiently, and consumption values are better—at least in theory.

In real life, a plug-in vehicle simply lets the driver enjoy the electric smoother ride for more time. If you’re not a hardcore petrolhead, I guarantee you’ll soon get addicted to EV benefits while driving a plug-in hybrid. It’s simply common sense, and only your personal experience will prove if I’m right or wrong.

This is a serious problem. Why? Because, you see, popular wisdom will incline the balance toward electrification, whether you like it or not, thanks to a number of other factors. We’ll delve into it in the second part of this editorial. Stay tuned.