What It’s Like To Teach Entrepreneurship In A North Korean Business School

North Korean “Tech School” business students eating in the cafeteria. Photo provided by Ewald Kibler

It was a week that had many of the elements you’d expect at a business school startup week: pitch sessions, students presenting their business models through slick PowerPoints, a venture capitalist on hand to give his two cents.

But that week in 2016 was very different for one reason: It was in Pyongyang, North Korea, and the students were pitching ideas they likely will never get to pursue, at least not for the foreseeable future.

“I still use my experience in North Korea to show some examples of teaching in extreme settings,” says Ewald Kibler, associate professor of entrepreneurship at Aalto University School of Business in Finland.

STUDYING DIGITAL BUSINESS EDUCATION IN NORTH KOREA

Ewald Kibler of Aalto University School of Business: “In all places, there is this kind of universal language. When you laugh together, when you bring in humor and some fun into the classroom, it is a way of breaking the ice, wherever you are”

In 2016, Kibler was one of six professors allowed to teach entrepreneurship during what was hailed as the first Startup Week in North Korea.

“I try to reflect on what I learned from it,” he says. “One of the things was that, in all places, there is this kind of universal language. When you laugh together, when you bring in humor and some fun into the classroom, it is a way of breaking the ice, wherever you are.”

Kibler is part of a research team that has published three papers about dynamics in the North Korean school they dubbed “Tech School.” The third, “Unfolding Dispositifs: Attempts at Digital Business Education in North Korea” was published this spring in the journal Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space. It examines in context how the school uses digital technology, how it controls it — and how students find ways to get around the rules.

One of Kibler’s Aalto colleagues and co-authors, Jukka-Pekka Heikkilä, taught entrepreneurship at the Tech School periodically between 2013 and 2017. Kibler, a trained sociologist, helped teach that startup week in 2016. Their research, Kibler says, is based on first-hand observations, student essays, and diaries, and is likely the first such research conducted through primary data.

Since Heikkilä’s last visit to North Korea, the country has significantly closed itself off further, making similar research based on first-hand data unlikely for years to come. All three papers offer a rare but fascinating glimpse into the life of North Korean students and the tensions between a paternalistic state and the economic, even entrepreneurial, activities that inevitably pop up.

Poets&Quants recently talked with Kibler about his latest research paper inside North Korea’s Tech School, his research team, and teaching entrepreneurship inside a dictatorship. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Let’s start with a little bit about your background.

I did my bachelor’s and master’s In sociology. I did my PhD in economic geography in Finland at the Turun School of Economics and soon after started as Assistant Professor in Entrepreneurship at the Aalto University. My research always focused on entrepreneurship in particular, but always always more from a geography, sociology, even policy lens. Now I’m a tenured professor at Aalto.

How were you connected with this North Korean school?

It all started with one of our postdoctoral researchers, Jukka-Pekka Heikkilä. He’s a bit of an adventurer, and he sent an email to the North Korean business school basically asking if he could teach information systems at the school. Half a year later, he got a response that he could come. So, he went to North Korea for the first time in 2013 as a teacher. Until 2017, he went there on a regular basis.

I was working with him on ways to collect data in such an extreme setting. We started to have a few ideas on what’s possible and also what would be approved by the school. At some point, we were able to do, at least, observations and a little more ethnographic work which was the most logical way to pursue it. We were also able to collect essays and diaries from the students. Essays, texts, narratives, and observations became the only way to go about the research in that school in such an extreme setting.

I only went to North Korea once in 2016. I also helped as a teacher for one week; We called it the first Startup Week in North Korea. There were a bunch of professors and other colleagues, and we were teaching entrepreneurship.

Tell me a bit about the research team.

In our most recent paper, the main ethnographers are Jukka-Pekka Heikkilä and Will Scott. Will Scott is not a researcher or a scientist, he was a teacher. He helped them basically enrich the observations and the data collection. Heikkilä is still in academia, about half and half. Thomas Wainwright and myself, we represented more the serious scientific researcher side. In that sense, we made a great team. Without Heikkilä and Scott, this paper would have not been possible, obviously.

Why were you interested in this project? A North Korean business school seems a bit contradictory.

I’m always always interested in geography and place research and different, extreme settings. For example, I did a study in Haiti after the earthquake on how communities recover from major disruptions. I’ve looked into outbreaks in Chile, but also regions that are more suppressed and communities where lots of inequalities are at play. I was always interested in extreme settings through the institutional lens – trying to understand how institutions are really shaping everyday life.

When I heard Heikkilä was going to North Korea, I was deeply into institutional research, also political research and geography. Because entrepreneurship is also about potential change, I thought it was a very intriguing setting. I approached it very neutral as any other setting that I find interesting, but obviously with North Korea, it was particularly unique or extreme. In this case, it was all about doing research within the setting of the school. We did nothing outside of the school campus.

Obviously it was a bit of an adventure. Many of my friends and colleagues asked me why I was interested in this. I was trained as a sociologist, so I was interested in the research side but also in developing a better understanding of people in North Korea. I think maybe our papers, at some point, will also make a contribution and shed some new light in a context where we usually don’t know much.

Going back to Startup Week in North Korea. I find that pretty interesting. Are people there even able to launch their own ventures? What kinds of things did you teach during that week?

Yes, in general, entrepreneurship or starting up a business is illegal for sure. It is not something North Koreans can do. But obviously, especially between maybe 2010-11 until 2016 -17, there was some slight opening in certain areas. There were some economic developments, and so called state owned enterprises, as well as some importing and exporting. There have been research papers on these things, even though I think our research is probably one of the first really based on primary data and not only based on refugees’ insights.

Clearly that mostly stopped after 2018-19. It is a completely new era, you could say, and it would be impossible for my colleague to go there again. But there was this window of opportunity to see a slight openness during that time. It was the first time ever that entrepreneurship became part of a curriculum in a school in North Korea. It’s not there anymore, but it was there for a couple of years. So there was a bit of something flourishing.

Business activities are common in North Korea. There are markets and hidden markets that shouldn’t exist but are fairly accepted.

Our Startup Week was a five-day course in entrepreneurship that we taught together as a group. We had different professors jumping in with different topics.

What were the student reactions to the course?

They were very engaged. Teaching in North Korea, you’re looking for the sad and depressed conditions. But we were surprised almost every day because you couldn’t see that so much. Things were pretty normal. We talked in English, and they spoke English fairly well. We wrote a special paper on how to teach in North Korea and really unpacked the different tensions that exist and how to navigate those.

In the Startup Week, students were pitching their business ideas, they developed business models, and we actually also had a venture capitalist with us helping as a teacher. It was a very special, very interesting week.

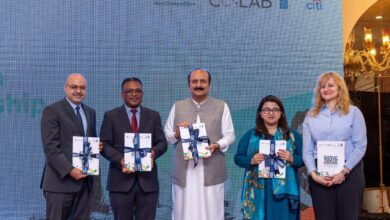

Inside the North Korean business school where Kibler and his colleagues held Startup Week and collected data for their three research papers. Photo provided by Ewald Kibler

What kind of technology and digital tools were the North Korean students allowed to use?

I think it’s always important to remember when we did that study, things might have slightly changed. Maybe one could say that it hasn’t developed much further. We know that the surveillance has increased again, substantially, after 2019, with the use of biometric data, facial imaging and whatnot.

But back then, the school had a local intranet that students were allowed to use, but only also in context with coursework. They also have their own phones, and they were allowed to have certain apps that were regulated. In some courses, especially those taught by Will Scott, there are some really rich vignettes that we have in the paper where students worked on their own apps to develop. There was an idea around creating an online dating app.

Of course, there are limits on what teachers are allowed to help with, but some students tried to push teachers sometimes to give them more information even if it wasn’t allowed. So there was a bit of tension all the time.

Students were really interested in software piracy and piracy in general. The local internet and the school’s intranet, students were allowed to use for specific labs. I think the KCC, the government computer lab, was linked to school labs so they could control and constrain what could be done.

I think coding was among the easiest to teach, within the boundaries. Scott mentioned there was quite a high level of coding already that was going on, so one can only assume that there are also spaces where maybe they can create their own codes and share codes.

You also wrote about the students keeping USB sticks to hold their data. Was that to get around some of the surveillance?

Exactly. I think we described it as “working around the constraints.” I think it was where the experimentation really came in a little bit more. As with the piracy example, I think that’s what students want to do everywhere. The more you learn and discover, you want to move on, experiment, and discover more.

But at the same time, knowing those limits. There is surveillance going on. You need to find some ways around it, like sharing with or storing stuff on a USB stick and sharing data. One of the examples in the paper is that they’d ask the teacher to share more via a USB stick because it is a fairly safe way to use your own data that is stored there.

What do you think is the most valuable aspect of your research and most recent paper?

We do use some complex but very important concepts, like Foucault’s concept of the dispositif and the concept of paternalist care and discipline. We used them as a kind of institutional logic of how things are done at the macro level, but also micro level. I think this paper really stands out for showing how logics are in contrast, but also showing how they work together. This also creates a setting of stability where actual development can happen, even under very extreme constraints.

I think that’s where we also need more research, in any setting. I do lots of research on how you run social enterprises, for instance. It’s always about combining things. With different logics, there are always tensions and paradoxes at play. And I think, here, we also have a bit of this processional perspective. We see how tensions unfold in situations, in actual spaces, in a lab, but at the same time how this reflects macro issues. So I think this duality of care and discipline we could vividly observe in the classroom, but at the same level, it reflects back to the state.

I think this paper at least shows that there is potential for development. Maybe smaller changes are possible without only a negative or very disruptive idea. It is a very realistic picture of how development and change can unfold, that is almost in line with what the state is trying to achieve. The state also tries to do good for their citizens in the one-to-one, but obviously, the dominant logic is to achieve this through control, power, and creating this tension. I think that makes this paper very, very special to unpack this tension. Care is also alive, it’s not only about surveillance and only about suppression.

You said your colleagues would likely not be able to go to North Korea today. Do you think the window has closed for further research like this in North Korean schools?

I assume that what we were able to do, together with my colleagues, and especially Jukka-Pekka Heikkilä, will be fairly unique for a long time. The funny thing is, we still sometimes get emails from the school, but the school could also be closed at any time.

As I said, this is primary data. There is really not much research out there, but even in the best research, we literally couldn’t find a single study that really builds on primary data. That was surprising to me. I invested many, many years to guide the research with my colleagues in the field, and I think we’re a good team. The research itself, I don’t think we will see similar studies for some time. All three papers might be unique for several decades.

But, that said, hopefully not. I’m trained in sociology which hopes to create immediate social impact and to change things. In business school, we also train more and more to do impact oriented research. One would hope that some of the insights may also trigger development and improvements, but also a better understanding.

Anything else you’d like to add?

From the education side, we, as professors, continuously try to improve our teaching and education. I still use my experience in North Korea to show some examples of teaching in extreme settings. I also try to reflect on what I learned from it. One of the things was that, in all places, there is this kind of universal language. When you laugh together, when you bring in humor and some fun, this is one way of experimenting in the classroom and of breaking the ice, wherever you are.

Obviously, maybe one could say this was happening in a bubble, but the classroom experience was quite fascinating to see as well as the level that the students achieved during the entrepreneurship courses. When I think back, I just appreciate that I at least had the chance to go there once and see how it’s done.

DON’T MISS: REGRETS? TOO FEW TO MENTION FOR DEPARTING GIES DEAN JEFF BROWN and TUCK’S VIJAY GOVINDARAJAN ON HOW DATA & AI WILL TRANSFORM PRODUCTS, COMPANIES & BUSINESS SCHOOL CLASSROOMS