What using artificial intelligence to help monitor surgery can teach us

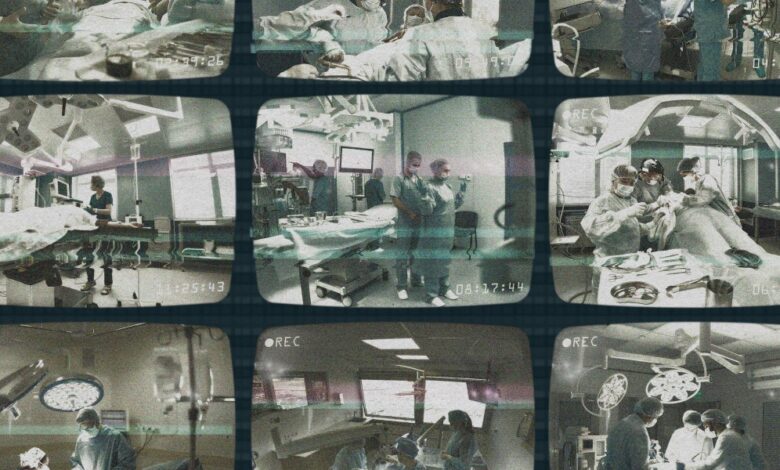

Teodor Grantcharov, a professor of surgery at Stanford, thinks he has found a tool to make surgery safer and minimize human error: AI-powered “black boxes” in operating theaters that work in a similar way to an airplane’s black box. These devices, built by Grantcharov’s company Surgical Safety Technologies, record everything in the operating room via panoramic cameras, microphones in the ceiling, and anesthesia monitors before using artificial intelligence to help surgeons make sense of the data. They capture the entire operating room as a whole, from the number of times the door is opened to how many non-case-related conversations occur during an operation.

These black boxes are in use in almost 40 institutions in the US, Canada, and Western Europe, from Mount Sinai to Duke to the Mayo Clinic. But are hospitals on the cusp of a new era of safety—or creating an environment of confusion and paranoia? Read the full story by Simar Bajaj here.

This resonated with me as a story with broader implications. Organizations in all sectors are thinking about how to adopt AI to make things safer or more efficient. What this example from hospitals shows is that the situation is not always clear cut, and there are many pitfalls you need to avoid.

Here are three lessons about AI adoption that I learned from this story:

1. Privacy is important, but not always guaranteed. Grantcharov realized very quickly that the only way to get surgeons to use the black box was to make them feel protected from possible repercussions. He has designed the system to record actions but hide the identities of both patients and staff, even deleting all recordings within 30 days. His idea is that no individual should be punished for making a mistake.

The black boxes render each person in the recording anonymous; an algorithm distorts people’s voices and blurs out their faces, transforming them into shadowy, noir-like figures. So even if you know what happened, you can’t use it against an individual.

But this process is not perfect. Before 30-day-old recordings are automatically deleted, hospital administrators can still see the operating room number, the time of the operation, and the patient’s medical record number, so even if personnel are technically de-identified, they aren’t truly anonymous. The result is a sense that “Big Brother is watching,” says Christopher Mantyh, vice chair of clinical operations at Duke University Hospital, which has black boxes in seven operating rooms.

2. You can’t adopt new technologies without winning people over first. People are often justifiably suspicious of the new tools, and the system’s flaws when it comes to privacy are part of why staff have been hesitant to embrace it. Many doctors and nurses actively boycotted the new surveillance tools. In one hospital, the cameras were sabotaged by being turned around or deliberately unplugged. Some surgeons and staff refused to work in rooms where they were in place.