At the end of the 1980s I become friendly with a fellow named John Knoll. A very likeable fellow who years later would go on to win Academy Awards for his work as creative and technical director of Hollywood’s Industrial Light & Magic.

But when I met him, he and his brother Thomas were busy working on software they had created and recently sold to a small software company in the niche typography market.

Of course the software was Photoshop, and the small publisher was Adobe, Inc. Both would go on to change our world.

Prior to purchasing Photoshop, Adobe had only had two products. Its own Adobe Illustrator, and a growing line of digital typography. Both of which ran on Adobe’s own Postscript language (see the best Adobe fonts here),

As visual artists working at that time, we could hardly imagine more powerful tools than Photoshop, Illustrator and a digital type library. And by 1999 Adobe brought out its InDesign for print page layouts. (InDesign was originally developed by Aldus, makers of PageMaker, which Adobe bought and killed.)

With InDesign added, Adobe owned the print design and publishing markets, but what was the company’s approach to the web?

Now, with the news that Adobe’s deal with Figma is no longer happening, I take a look at the software company’s complicated (and disappointing) relationship with online publishing – and ask, is it likely to be left behind?

Daily design news, reviews, how-tos and more, as picked by the editors.

And then came the web…

While Adobe was solidifying its control over the print publishing market, a brand new world of publishing was taking form. The Internet.

And through the ’90s and ’00s, Google was cornering web search and online advertising. Netscape, Safari and Explorer were duking-out the browser wars.

But Adobe seemed largely uninterested in the internet. Yes, it did purchase the very popular GoLive web application in 1999, and began a round or two developing LiveMotion, a Flash knock-off. But both were later abandoned by Adobe and left for dead.

How odd the owner of the print publishing world, had no real footprint in internet publishing. Over half a decade would need to pass. And in 2005 Adobe bought its largest competitor Macromedia. It inherited Dreamweaver, Flash, Director, Fireworks, and others. Once again, in the years that followed Adobe would either destroy or discontinue most of them. (Both Dreamweaver and the former Flash are still alive today, despite few customers having interest.)

The demise of Flash

Adobe had inherited both the Flash plugin, and Director’s Shockwave plugin with the Macromedia purchase. These were the two most broadly installed browser plugins in the world. In 2011 Flash had a 99% installed base, and Shockwave 41%. Together they represented total control over the internet for games, interactivity, productivity, and even immersive web design – think blockbuster movie websites.

Yet after the row between Steve Jobs and Adobe over Flash, Adobe simply shut down both Flash and Shockwave, and walked away from its massive control of the web.

Why does Adobe appear to have such an aversion to the web?

The demise of Flash left a huge hole in the Internet’s functionality, as HTML5 has still never truly replaced the power of Flash and its Actionscript. But it also left a huge hole in Adobe’s line of web creation software.

Enter: Muse

By 2012 Adobe had killed off many programs and was poised to kill Creative Suite. So as an enticement for customers to move over to Creative Cloud, Adobe brought out an app that they knew everyone wanted: ADOBE MUSE, the “no-code” web layout/publishing program for traditional page designers. After a couple of glitchy years and a re-write, Muse started delivering on its promises. Designers were able to produce beautiful and stunningly capable websites, without needing any code.

Muse was given the full roll-out. Great marketing, books and classes. Adobe was showing a real commitment, and it was paying off. Muse was catching on and spawning a huge third party market of plugins and template offerings. Professional services like Shopify and MailChimp integrated with Muse. From 2014 through 2017 its popularity grew, spawning millions of Muse websites.

In Muse, Adobe found a poster child for the success it had always needed in the web sphere. And users truly loved the application. Alas, all good things pass.

The decline and fall of Muse

To support Muse, Adobe had launched its “Business Catalyst” web hosting, Adobe TypeKit web type servers, the “Edge” line of web apps. Plus Flash/Director were made able to build mobile and desktop apps. (Spoiler: Every one of those projects are now dead.)

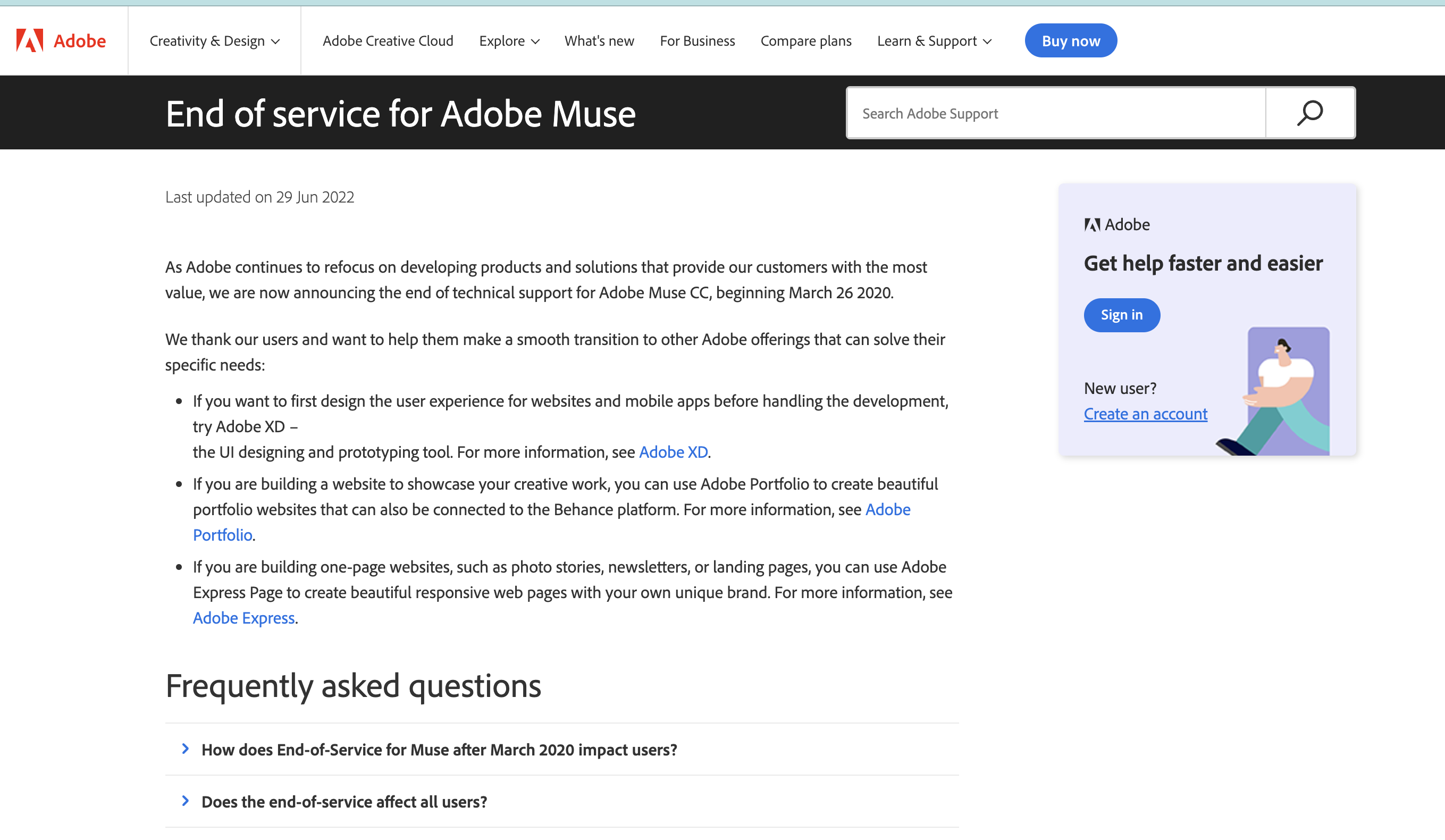

But in 2018, at the very height of Muse success, Adobe placed Muse into “End of Life” status. No more upgrades or bug fixes. No legitimate reason was ever given as to why, and no real replacement options ever offered.

The internet lit up with angry customers. Petitions were signed with tens of thousands of users asking Adobe to reconsider Muse. Class action lawsuits were threatened by angry users. Thousands complained on web forums how they had based their entire business on Muse. And how discontinuing Muse would end their businesses.

It’s been five years since Muse development ended (and amazingly it still outputs wonderful and functional websites). It is still available as a “legacy” app to those that pay for the entire Creative Cloud subscription, so many do. Many paying over $700/year just for access to Muse!

Why? Because while Adobe appeared to not fully understand it, its customers realised how much better Muse was than the competition. Certainly for the non-programming designer. In other words, Adobe’s traditional and core customer.

Adobe customers of the 2010s understood how important it was to have the same triumvirate of art/graphics/publish. This used to be PS, AI and InDesign. But since it’s release in 2012 it had become PS, AI and MUSE.

Every year Adobe has been dismantling more and more of the support systems around Muse. Users have persevered, finding ways to keep most features working. When Muse began to crash after selecting the FTP UPLOAD command, Muse users found a work-around, and shared it on their Muse Facebook forum.

In the Spring of 2023 Adobe did the unthinkable: It shut down its TypeKit servers. And without warning all Muse sites across the world lost all custom fonts. Frutigers became Helveticas. Another work-around was found, and soon Muse sites came back running Google Fonts instead!

Then in early December of 2023, Adobe’s reduced quality control attacked again. In what should have been a simple upgrade to the Creative Cloud application, Adobe broke Muse again. After the upgrade Muse was unable to fully boot on Mac or Windows.

Yes, the remaining Muse users found a very kludgy and temporary work-around. But for the over $700/year one might expect better. So in December when they once again reached out to Adobe and got little to no response, it was more than disheartening.

Is Adobe going to be left behind?

Adobe currently brings in over $15 billion US every year. So clearly it is doing many things right.

But here we are nearly 30 years into the internet age, and our leading provider of publishing tools hasn’t any dog in the fight. Adobe has failed to provide us with appropriate web tools. The way it has for decades in the print, graphics and video markets.

The problem is, I think the print markets haven’t existed for many years. Most communications work is web based. That means Adobe customers have to go outside the Adobe ecosystem to find appropriate web tools. Some went to Elementor, a page builder addon for WordPress. Others went to Webflow, Wix or similar proprietary drag & drop system.

The only way to retain our supporting Adobe tools (PS, AI, ID, maybe XD) is with the full Creative Cloud suite costing over $700US/year. Add the cost of $300US and up per year for the web tools, and we are looking at over $1,000US/year.

That’s a huge increase over just a few years ago when you could get all your tools, including Muse, from Adobe for under $600US/year.

Defining success

In full candor, I am faulting Adobe for not being as perfect in every category, as it is in most. Admittedly an unfair bar.

Regardless, we will see creatives continue to change vendors once they find compelling open source options, and companies like Affinity, who offer their full suite, non-expiring, for a one time payment of $165US. A fraction of Adobe’s costs.