Why Liquid Cooling Systems Threaten Data Center Security, Water Supply

COMMENTARY

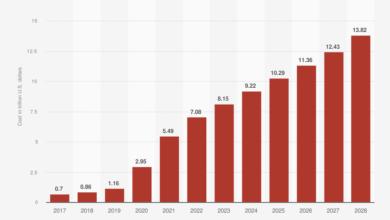

In our digitally driven world, data has become an invaluable asset to companies across sectors. Data enables intelligent products, services, and operations. Data is also the unsung hero in today’s “age of AI.” By 2030, the AI market will be worth more than $1.3 billion in revenue — growing 36.8% from 2023’s market size of $150.2 billion, and data is arguably the catalyzer driving this immense growth.

The Current State of Data Centers

Data is not just an intangible asset that’s stored in the virtual ether of “the cloud.” In reality, data, and data storage, is very much tied to the physical world. With the increasing introduction of artificial intelligence models, more data will be needed, and therefore stored in data centers.

These centers allow for data to be kept secure, accurate, available, and, for all practical purposes, “alive.” Using switches, storage systems, servers, routers, and other equipment, data centers can store essential data sets around the clock. However, the extreme warmth produced by the energy used to process and store data causes overheating concerns. Data centers therefore require energy-intensive cooling systems to ensure the equipment does not fail. Such failures can lead to data losses, and vital workload and service outages — which occurred at a major tech company’s Australian-based data center when a regional utility’s power outage shut down the center’s cooling mechanism.

Unfortunately, cooling comes at a steep price, accounting for nearly 40% of an average data center’s electricity usage. Many operators recognize the strain traditional air-based cooling methods put on its finances and net-zero pledges, which is why some are opting for liquid cooling systems. Although liquid cooling is technically more energy efficient than air cooling, it can still negatively impact the environment — and opens other door for potential outages.

Data’s Dependence on Water

When we say “liquid” cooling systems, we’re actually referring to water in most cases. Just like living beings, data needs water to survive — and, therefore, so do AI models, software, and countless other technologies that rely on data.

Most data centers in the United States use freshwater supplied by utilities — the same water supply that humans rely on. The average data center uses 1 million to 5 million gallons of water a day (paywalled article), and considering that 30% of the world’s data centers are located in America, that means Americans are losing access to a significant amount of safe drinking water.

The US is already experiencing alarming water shortages as a result of low precipitation fueled by climate change and increased demand from a growing population. Now, add the increased demand from data centers as operators try to cool facilities overrun with AI-associated data, and America could experience a water crisis.

To make matters worse, the American water supply is facing an additional threat: cybersecurity attacks. Bad actors are increasingly targeting US water infrastructure. The main concern is the health and safety of Americans, but these attacks also threaten data centers — and the technology that depend on data. Hackers have historically targeted cooling systems, and they will undoubtedly continue to do so by finding weak points in data centers’ water infrastructure, as well as security gaps in the regional water utilities that serve data centers across the US.

Two-Pronged Approach: Sustainability and Security

So, how can data center operators effectively store data that is essential to the booming AI market and virtually every aspect of the digital world while limiting their water consumption and protecting their water infrastructure?

From an environmental standpoint, it will mean utilizing other water sources beyond freshwater provided by American utilities. Some operators are exploring the use of wastewater, industrial water, and seawater to lessen their strain on the United States’ depleting freshwater supply. Improving liquid cooling system monitoring tools to track water consumption is also key. And companies are wisely utilizing federal funds to explore efficient cooling options and should continue partnering with the public sector moving forward.

What’s more, operators should consider introducing new liquid cooling systems entirely, as there are now more advanced designs that use less water. And as new data centers become necessary — which we know they will — companies should consider building these facilities in cooler climates as well as in areas with water basins that are not overstrained.

From a cybersecurity standpoint, many operators will have to prioritize defensive measures that specifically protect water infrastructure — which arguably has not been a key security prerogative in previous years. This will require a strategic reset in which leaders identify water, energy, and other external dependencies and extend risk assessments to environmental and other resources beyond the “logistics-based supply chain” that could interrupt business or operations. If enterprises have not done so already, then they should also apply zero-trust principles to all water-based infrastructure that they are dependent upon.

Organizations must prepare themselves for a variety of scenarios: What would happen if the data centers you rely on for business viability had a water shortage that forced a shut down? Does your crisis plan consider catastrophic loss of water, and therefore data? If water resources and infrastructure sit outside of your security programs, then chances are you could very well face these scenarios.

To avoid such potential threats, keep in mind this simple mantra: Define. Protect. Defend. Assess your risk so you can mitigate it, and monitor and maintain your defenses.

That said, water utilities must also do their part to help prevent attacks that could severely impact critical data centers and compromise water supply. Experts point to a renewed focus on cyber resiliency through public-private partnerships, improved centralized patch management systems, risk assessments, and temporary controls to address immediate vulnerabilities in critical systems and legacy infrastructure.

Change Is Needed Now

Data center operators are faced with a considerable challenge. They must meet the demands of storing an astonishingly increasing quantity of data while utilizing a decreasing supply of water to cool their facilities. Business, technology, and sustainability leaders must work together to formulate strategies that not only protect the environment, but also protect their data.

There’s no future for humans or the life-changing technology we’ve come to rely on without water. And make no mistake, we are potentially encroaching on a water supply crisis if data center operators, utilities, and the American government do not implement preventative measures now.