Why the Middle Class of Business Deserves More Attention from Entrepreneurs – Darden Report Online

By Gosia Glinska

Silicon Valley exhorts entrepreneurs to supersize their dreams: Have a crackerjack idea with disruptive potential, raise lots of funding from investors, scale up rapidly and hit a billion-dollar valuation.

Awash in stories of “unicorns” and “gazelles” — the rare high-tech high-growth firms that capture the headlines — many founders chase the dream of launching the next Stripe or Instacart.

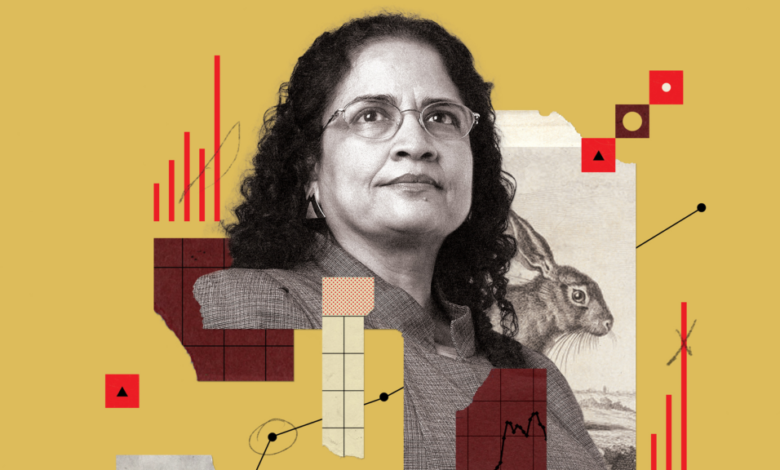

“But is that the only dream worth having?” asks Darden Professor Saras Sarasvathy, a leading expert on the cognitive basis for high-performance entrepreneurship and the 2022 winner of the Global Award for Entrepreneurship Research from the Swedish Entrepreneurship Forum.

“In a business school, we shouldn’t just be teaching high-growth, high-technology entrepreneurship. We should be teaching students how to build a middle class of business — companies that foster robust communities, create value for stakeholders, create jobs and last long enough to give an entrepreneur a good life.”

Professor Saras Sarasvathy, 2022 winner of the Global Award for Entrepreneurship Research from the Swedish Entrepreneurship Forum

“In a business school,” says Sarasvathy, “we shouldn’t just be teaching high-growth, high-technology entrepreneurship. We should be teaching students how to build a middle class of business — companies that foster robust communities, create value for stakeholders, create jobs and last long enough to give an entrepreneur a good life.”

Alumni Lighting the Way

Sarasvathy is quick to point out that many Darden alumni have built or are building such companies.

Take Manoj Sinha (MBA ’09), co-founder and CEO of Husk Power Systems. Sinha launched Husk in 2008 to solve an intractable problem afflicting three billion people around the world: lack of access to reliable and affordable power. Today, Husk provides electricity to 50,000 households, small businesses and factories in India, Nigeria and Tanzania through renewable energy-powered, decentralized minigrids.

But Husk delivers more than electricity to remote areas. Sinha — recently named to Time magazine’s list of the 100 most influential climate leaders in business — estimates that his company is responsible for creating around 20,000 jobs.

“When we install minigrids in a community, we look at what might be brought in as a set of entrepreneurial activities that will help people use electricity more productively and generate new income sources. That’s how our business model became successful.”

Manoj Sinha (MBA ’09), Co-founder and CEO, Husk Power Systems

“When we install minigrids in a community,” says Sinha, “we look at what might be brought in as a set of entrepreneurial activities that will help people use electricity more productively and generate new income sources. That’s how our business model became successful.”

Another notable middle-class venture started by Darden alumni is 501 Auctions. The company, co-founded in 2011 by Jon Carrier (MBA ’12) and Teddy Jones (MBA ’12), developed a fundraising platform for nonprofit organizations, changing the way charity events are run.

“501 Auctions is a for-profit business that helped fund the growth of nonprofits,” says Sarasvathy. “It raised more than half a billion dollars in charity contributions. It’s a business that creates value in multiple ways.”

Haiama Beauty, a business founded by Allison Shimamoto (MBA ’19), is poised to become the next Darden-founded middle class company, per Sarasvathy. As she puts it, “Allison is truly solving a problem — offering toxin-free products for Type 4 curly hair.”

Shimamoto uses ethically sourced, plant-based ingredients from South America, choosing to partner with female suppliers who employ workers from local villages.

None of these Darden founders started by chasing venture capital and unicorn status, notes Sarasvathy. Instead, they focused on tackling real problems and on building not just great companies but also a better world.

Defining the Middle Class of Business

Sarasvathy has coined the term “middle class of business” to describe companies that grow and endure over time, but don’t grow very large in size.

In her paper, “The Middle Class of Business: Endurance as a Dependent Variable in Entrepreneurship,” published in Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Sarasvathy defines the category as ventures that have between five and 300 employees and profitably survive for at least 16 years.

Even though firms that endure for 16 years or more have slower growth than younger firms, they actually employ the most people, studies show. “If we aim to spur job creation and economic development,” says Sarasvathy, “endurance over time is a better predictor than size. That’s one reason we should foster the development of a middle class of business.”

The question is how.

Darden professor Saras Sarasvathy is recognized around the world for her research on “effectuation,” the unique logic expert entrepreneurs use to build new firms and markets.

Teaching Entrepreneurship Like We Teach Science

Sarasvathy, along with Professor Sankaran Venkataraman, has long believed in teaching entrepreneurship the way we teach science — to everyone who has access to education. As she puts it, “Today, we teach the scientific method not only to potential scientists in professional schools but to everyone, starting at an early age, as an essential mindset and skill.”

But science wasn’t always considered teachable. Before Francis Bacon started to spell out the key elements of the scientific method, science was the rarefied domain of those who had wealth, time and a spark of divine revelation.

According to Sarasvathy, democratizing this knowledge so that it was widely accessible spurred technological progress, which increased productivity. “For the first time in history, a large swath of society was able to earn enough money to escape poverty,” says Sarasvathy. “This led to the emergence of the middle class, defined by income.”

In her “The Middle Class of Business” paper, Sarasvathy draws a historical parallel. She argues that — just like the introduction of science education to all fostered the rise of the middle class — the introduction of entrepreneurship education to all would spur the rise of a middle class of businesses.

“When we start teaching entrepreneurship to everyone as a necessary skill,” argues Sarasvathy, “people will be more entrepreneurial, not only in starting companies but also in solving problems in their lives and in the world. People won’t be necessarily starting more companies; they’ll be building better ones that endure for longer than average periods of time and create more value.”

Developing the Entrepreneurial Method

But can entrepreneurship be taught? If you ask Sarasvathy, who’s been teaching it at Darden since 2004, the answer is a resounding yes.

In fact, Sarasvathy pioneered the framing of entrepreneurship as a method à la the scientific method in her groundbreaking book, Effectuation: Elements of Entrepreneurial Expertise. She further developed the concept in “Entrepreneurship as method: Open questions for an entrepreneurial future,” a 2011 article co-authored with Venkataraman and published in Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice.

The cornerstone of the entrepreneurial method is effectuation — the unique logic expert entrepreneurs use to build successful companies. Sarasvathy discovered this logic, which she distilled into five teachable principles, in the late 1990s as a result of in-depth studies of how expert entrepreneurs think, act and make decisions in the initial stages of venture creation.

Effectuation is rooted in nonpredictive control. “Instead of trying to predict the future in order to control it, which is thinking causally,” says Sarasvathy, “expert entrepreneurs know from experience that if they control certain things in the present, they can create the future. That is thinking effectually.”

“Most startups are not VC-backed, high-growth ventures. What if you built a company that lasts 15, 30 years, and pays double what you’d earn as an MBA? Let’s say you earn $500,000 a year as a founder for the next 30 years, and at the end you sell your company for anywhere between 30 and 60 million dollars. Isn’t this a dream worth having?”

Professor Saras Sarasvathy

Effectual entrepreneurs start with immediately available means — who they are, what they know and whom they know — to come up with doable venture ideas. They control the downside by investing only what they can afford to lose. They collaborate with self-selecting stakeholders who are willing to commit resources to their fledgling ventures.

“The goal is to co-create rather than predict the future,” says Sarasvathy, often with surprising results.

Shimamoto, for one, created an outcome she didn’t expect. The hair cream she developed was intended for curly hair. She was surprised to find that customers with all kinds of hair were buying her product.

As Sarasvathy puts it, “Allison developed this niche product, trying to solve a problem for individuals with Type 4 hair. It turns out that her solution is applicable to a much wider group of people.”

Pursuing a Worthy Dream

The Silicon Valley model of entrepreneurship has captured the imagination of the public, and many founders want to emulate it, despite the fact that it reflects only a sliver of startups.

“Most startups are not VC-backed, high-growth ventures,” says Sarasvathy, who encourages her students to build enduring businesses instead. She asks, “What if you built a company that lasts 15, 30 years, and pays double what you’d earn as an MBA? Let’s say you earn $500,000 a year as a founder for the next 30 years, and at the end you sell your company for anywhere between 30 and 60 million dollars. Isn’t this a dream worth having?”

That dream worked out well for Carrier and Jones, who grew 501 Auctions to more than a hundred employees without seeking outside investments.

When they launched their venture as Darden students, Carrier and Jones didn’t expect that five years later they’d be bombarded with offers from interested buyers. They ended up selling because they could do so on their own terms.

While 501 Auctions continues to create value for nonprofits under a different name, its sale gave Carrier the freedom to choose what’s worth pursuing. “After the sale,” he says, “I had a lot of personal flexibility for what came next in my career. I was a successful entrepreneur, and I had gained a lot of technology and startup skills with 501 Auctions.”

Unsurprisingly, Carrier decided to use those skills to build another venture, REI Hub. He enjoys the freedom of running his own business. “It’s challenging and rewarding,” he says. “I can’t imagine doing anything else.”

Batten Institute Support for Entrepreneurship Research

This article was produced by the Batten Institute for Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Technology, of which Professor Sarasvathy is an academic director.

The Batten Institute supports Sarasvathy’s research and her and other faculty’s curricular offerings in entrepreneurship — including courses such as “Effectual Entrepreneurship,” “Starting New Ventures” and “Venture Velocity” — through its Batten Faculty Fellows program. The institute also helps disseminate Sarasvathy’s influential research on the cognitive basis for high-performance entrepreneurship through the Effectual Thinking & Action Initiative.

Founded in 1999, the Batten Institute seeks to challenge Darden students to fulfill their entrepreneurial potential through transformational learning experiences and groundbreaking research in its focus areas of startup creation, VC, entrepreneurship through acquisition, technology and corporate innovation.