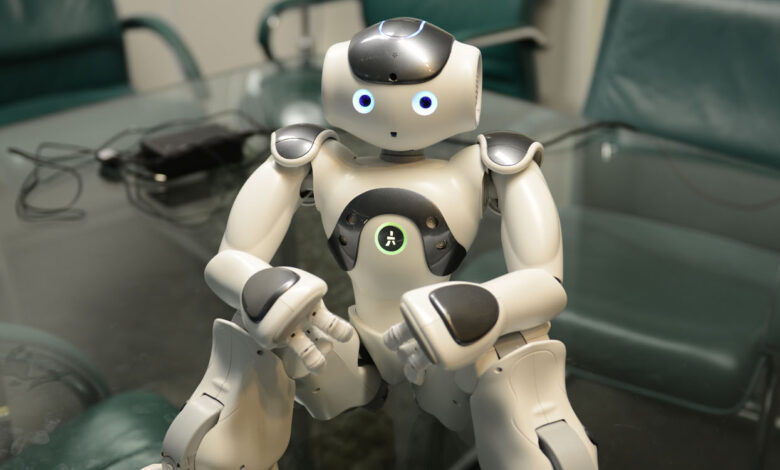

Young children are more likely to trust information from robots over humans

A recent study published in the journal Computers in Human Behavior sheds light on how young children decide who to trust when faced with conflicting information from humans and robots. Researchers found that children aged three to six are more likely to trust robots over humans when both sources of information are established as reliable.

The motivation behind the study was to understand how children decide whom to trust when faced with conflicting information from humans and robots. With the increasing presence of robots and other technological devices in children’s lives, it is important to explore how these interactions influence their learning and development.

For their study, the researchers recruited 118 children through various channels, including mailing lists, social media, and the website Children Helping Science. After excluding data from seven children who failed preliminary checks, 111 participants were included in the final analysis.

The study was conducted online using the Qualtrics survey platform, with parents guiding their children through the process. Children were randomly assigned to watch videos featuring one of three pairs of agents: both a reliable human and a reliable robot, a reliable robot and an unreliable human, or a reliable human and an unreliable robot. This setup allowed researchers to compare children’s preferences for reliable versus unreliable agents across different conditions.

The study comprised three phases: history, test, and preference. In the history phase, children watched videos where the human and robot agents labeled familiar objects. Depending on the condition, one agent consistently labeled objects correctly while the other labeled them incorrectly. This phase aimed to establish the reliability or unreliability of each agent in the children’s minds.

In the test phase, children were shown videos of the same agents labeling novel objects with unfamiliar names. They were first asked whom they wanted to ask for the name of the object (ask trials), and after hearing both agents provide a label, they were asked which label they thought was correct (endorse trials). This phase measured the children’s trust in the agents based on the reliability established during the history phase.

Finally, in the preference phase, children answered questions assessing their social attitudes toward the agents. These questions included who they would prefer to tell a secret to, who they wanted as a friend, who they thought was smarter, and who they preferred as a teacher.

As expected, the researchers found that children were more likely to trust the agent that had been established as reliable in the history phase. In the test phase’s ask and endorse trials, children showed a clear preference for asking and endorsing the reliable agent’s labels over those of the unreliable agent.

Notably, however, in the reliable-both condition (where both agents were reliable), the robot was more likely to be selected by the children. This suggests that even when both the human and robot were reliable, children showed a preference for the robot.

Age also played a significant role in trust decisions. Older children showed an increasing preference for humans, especially in the condition where the human was reliable. However, younger children displayed a stronger preference for the robot.

In the preference phase, children’s social attitudes further reflected a general favorability towards robots. They were more likely to choose the robot for sharing secrets, being friends, and as teachers, particularly in the reliable-robot condition. This preference extended to perceiving the robot as smarter and more deliberate in its actions. When asked who made mistakes, children in the reliable-robot condition were more likely to attribute errors to the human, suggesting that they saw the robot as more competent.

These results challenge the assumption that children inherently prefer human informants over robots. Instead, they suggest that children are willing to trust robots, especially when these robots have demonstrated reliability. This willingness to trust robots over humans has significant implications for how robots and other technological agents might be integrated into educational and developmental contexts for children.

While this study provides valuable insights, it has limitations to consider. The online nature of the study and the use of videos instead of live interactions may not fully capture the nuances of child-robot interactions. Replicating the study in a real-life setting could provide more accurate results. Additionally, the novelty effect—where children’s high initial interest in robots might bias their responses—should be considered. Long-term studies could help determine if children’s trust in robots persists over time.

The study, “When is it right for a robot to be wrong? Children trust a robot over a human in a selective trust task,” was authored by Rebecca Stower, Arvid Kappas, and Kristyn Sommer.